- HOME

- INTRO TO THE FORUM

- USE AND MISUSE

- BADLY WRITTEN, BADLY SPOKEN

- GETTING

TO KNOW ENGLISH - PREPARING FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TESTS

- GOING DEEPER INTO ENGLISH

- YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

- EDUCATION AND TEACHING FORUM

- ADVICE AND DISSENT

- MY MEDIA ENGLISH WATCH

- STUDENTS' SOUNDING BOARD

- LANGUAGE HUMOR AT ITS FINEST

- THE LOUNGE

- NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

- ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

- Long Noun Forms Make Sentences Exasperatingly Difficult To Grasp

- Good Conversationalists Phrase Their Tag Questions With Finesse

- The Pronoun “None” Can Mean Either “Not One” Or “Not Any”

- A Rather Curious State Of Affairs In The Grammar Of “Do”-Questions

- Why I Consistently Use The Serial Comma

- Misuse Of “Lie” And “Lay” Punctures Many Writers’ Command Of English

- ABOUT JOSE CARILLO

- READINGS ABOUT LANGUAGE

- TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

- NEWS AND COMMENTARY

- BOOKSHOP

- ARCHIVES

Click here to recommend us!

YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

Jose Carillo’s English Forum invites members to post their grammar and usage questions directly on the Forum's discussion boards. I will make an effort to reply to every question and post the reply here in this discussion board or elsewhere in the Forum depending on the subject matter.

How plain and simple English and advertising language differ

Question sent as private message by Totodan, new Forum member (December 5, 2011):

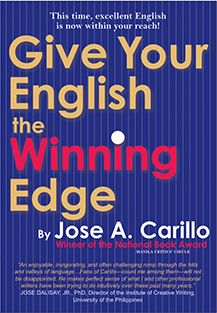

Hi, Joe! I recently bought your book Give Your English the Winning Edge. Written at the topmost part of the cover, right above the title, is the statement: “This time, excellent English is now within your easy reach!”

There is something about the statement that makes me uncomfortable. I think it could have done away with either the phrase “this time” or the word “now.” Having both of them in that statement sounds like excessively emphasizing the present, don’t you think?

I hope I don’t sound irreverent, Joe, knowing how punctilious and careful you are in your work. I’d be happy to be proven wrong.

But let me state on record that I find the book extremely authoritative and an outstanding supplement to your earlier work, English Plain and Simple.

Warmest regards to you and to all Forum readers!

My reply to Totodan:

I’m delighted to know that you have bought a copy of my book, Give Your English the Winning Edge. I’m sure you’ll find it a reliable informative resource in your continuing quest for better English.

That comment of yours is very perceptive, Totodan, and I’d like to assure you that you’re not being irreverent at all in calling my attention to the language of that blurb for my book. In fact, I’m glad that you’ve given me this opportunity to explain why I phrased that blurb precisely this way:

“This time, excellent English is now within your reach.”

You said that this blurb makes you uncomfortable for sounding like it’s excessively emphasizing the present. Your feeling is that it would read better if it does away with either the phrase “this time” or the word “now,” as follows:

“Excellent English is now within your reach.”

or:

“This time, excellent English is within your reach.”

I’m sure that with this opportunity to look at all three variations of the blurb, you can begin to feel and fully appreciate the difference in their shades of meaning.

To begin with, both of your suggested versions have only one overt time frame in mind: the present.

The first, “Excellent English is now within your reach,” denotes a present condition or state without alluding to a previous one; it simply declares that at present, excellent English is now within the reach of those being addressed. I would say that from an advertising standpoint, it’s a ho-hum, almost trivial statement that’s not particularly worthy of a second look.

The second, while grammatically correct, is semantically problematic. Read it more closely to see what I mean: “This time, excellent English is within your reach.” Without the implicit inference to a previous condition or state (the silent “then” implied by the adverb “now” in your first version), there’s a certain disconnect between the qualifier “this time” and the clause “excellent English is within you reach.” Indeed, without “now” in the main clause, the adverbial modifier “this time” becomes grammatically superfluous. In fact, that “now”-less version of the blurb, “This time, excellent English is within your reach,” is a trivial declarative statement—one definitely not worthy of being used as a come-on for the book.

This brings me to why I decided to use this more attention-getting blurb instead:

“This time, excellent English is now within your reach.”

That statement explicitly operates on two time frames: (1) the time (“the last time”) when the book being touted wasn’t available yet, which can be inferred from the use of “this time,” and (2) the present continuing condition denoted by the adverb “now” in the main clause. We can better understand the sense intended by that statement by going over the following bit of dialogue:

Speaker #1: “I don’t have the courage to propose to Sally. When I courted her four years ago, she dismissed me as nothing but a good-for-nothing AB undergrad.”

Speaker #2: “But that was the last time. This time, you are now a full-fledged lawyer. Go for it!”

Now, see how the drama in Speaker #2’s retort all but vanishes when we take out “this time” from the second sentence:

Speaker #1: “I don’t have the courage to propose to Sally. When I courted her four years ago, she dismissed me as nothing but a good-for-nothing AB undergrad.”

Speaker #2: “But that was the last time. You are now a full-fledged lawyer. Go for it!”

See also the same thing happen when we take out “now” from that second sentence:

Speaker #1: “I don’t have the courage to propose to Sally. When I courted her four years ago, she dismissed me as nothing but a good-for-nothing AB undergrad.”

Speaker #2: “But that was the last time. This time, you are a full-fledged lawyer. Go for it!”

I hope that by this time, it’s already clear why I phrased that blurb for my book that way. We can say that this is actually a little demonstration of the difference between plain and simple English, on one hand, and the language of advertising, on the other. The first primarily aims only to be clearly understood; the other, to catch your attention by using much more emphatic language in the hope that you’ll buy the idea—in this particular case, to buy the book.

Rejoinder by Totodan (December 7, 2011):

As I said, Joe, I’d be happy to be proven wrong, and having now seen the blurb in that perspective, I am indeed sufficiently convinced. I guess that is one shortcoming I have, this lack of appreciation of the exacting language required in successful advertising. This is not to say that I find the English used in advertising quite complicated. It's just that for far too long I have been exposed to too much corporatese and office gobbledygook, and so as not to acquire those bad habits, I have trained myself—both as writer and as teacher to my staff—to in the most concise manner. I'm glad you have explained it to me in the way that you did. This time, I shall now always keep in mind to have that perspective. I hope I said that right?

My reply to Totodan:

That’s right, Totodan! I’m delighted that you’ve now gotten the hang of it.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Does the pattern “...because of which ...” exist in English?

Question by Hairsyler, Forum member (December 8, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

Please let me know if the pattern “....because of which ...” exists. I rarely see that pattern.

My reply to Hairstyler:

Yes, the pattern “because of which” exists and is legitimate usage in English grammar. It means “on account of which,” as in this sentence: “I regret reading that horror novel, because of which I hardly slept last night.” Note that the comma before the subordinate clause is a must in such constructions in the same way as in its equivalent sentence using “on account of which”: “I regret reading that horror novel, on account of which I hardly slept last night.”

Without that comma, both "because of which" and "on account of which" constructions become dysfunctional, turning into run-on sentences:

“I regret reading that horror novel because of which I hardly slept last night.”

“I regret reading that horror novel on account of which I hardly slept last night.”

P.S. Some English speakers don’t feel comfortable using the “because of which” pattern. They’d rather use its semicolon-punctuated equivalent, as follows:

“I regret reading that horror novel; because of it, I hardly slept last night.”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Some more tough choices on article usage in English

Question by English Maiden, Forum member (November 27, 2011):

Sir, I’m not quite sure which kind of articles to use in the following sentences:

“My mother is (a/the) perfect mother.”

“This is (a/the) perfect time to go shopping.”

“These are (no article/the) perfect books to read in my free time.”

“We need to come up with (a/the) perfect backup plan.”

Please explain to me which kind of articles to use and why.

P.S. Also, why can we say or write “I had A FEAR of falling from high places when I was in high school” during the first mention of the noun FEAR or when we are establishing for the reader/listener the existence of such a fear, but not “I have AN ABILITY to spell my name backwards,” given the exact same instance or intent as with the 1st sentence?

My reply to English Maiden:

All of the four “perfect”-using sentences you presented should use the article “the.” They are socially acceptable idiomatic overstatements that would lose their cogency if the article “a” or no article is used instead. So even if nothing’s perfect and you know in your heart that they are not exactly truthful, don’t hesitate to say those statements as follows:

“My mother is the perfect mother.”

“This is the perfect time to go shopping.”

“These are the perfect books to read in my free time.”

“We need to come up with the perfect backup plan.”

As to your question about the usage of the perfect tenses in the two sentences you presented, the difference between those sentences is as follows:

When you say “I had a fear of falling from high places when I was in high school,” you need to use the past perfect “had a fear” because based on that declaration of yours, that fear was a subsisting (continuing) condition during the time that you were in high school, and it can be inferred from that statement of yours that you no longer have that fear at present (today).

In contrast, when you say “I have an ability to spell my name backwards,” you need to use the present perfect “have an ability” because based on that declaration of yours, that ability to spell you name backwards has been a longstanding ability of yours that subsists up to the present. The present perfect is the tense that denotes that continuing condition.

Rejoinder from English Maiden:

Thank you for your explanation for using the before the word “perfect.” It is clear to me now. But what if I don’t want to express cogency or make my sentence sound compelling, would it be okay to precede the word perfect with the indefinite article using the same structure, as with "This is a perfect time to go shopping”? Or is that sentence grammatically and semantically wrong?

Also, I wasn’t asking about the use of the past perfect or present perfect in the sentences I presented with the subjects “fear” and “ability.” What I wanted to clarify was the use of articles in those sentences. I notice that the noun fear can occur with the indefinite article, as in “I have a fear of heights,” but the noun ability usually takes the definite article, even if it’ s being used in an indefinite, non-specific sense, as in “I have don’t have the ability to sing." Why is that?

You see, sir, I’m still having so much trouble with the definiteness and indefiniteness, and specificity and generality of nouns. For some reason, I can’t make heads or tails of when the noun, especially when it is countable and in the plural, is being used in an indefinite or definite sense, or in generic or specific reference. I don't think I even fully understand what those terms mean in the first place. What exactly do those four terms—definite, indefinite, generic, and specific—mean anyway? If you could explain to me in detail and simple terms the rules that govern article usage in the English language, I would really appreciate it.

And finally, sir, I need your opinion on this tweet that I just posted: “My uncle has a weird habit of talking to and feeding lizards in his room.” Is my use of the indefinite article before the noun “habit” correct? What about my not using an article before the noun phrase “lizards in his room”? Is it correct as well? And suppose I had written that tweet this way: “My uncle has a weird habit of talking to and feeding the lizards in his room.”

Would there be any difference in meaning if I chose to use the definite article “the” before the noun “lizard”? Quite frankly, sir, I can’t think of what difference in meaning, if any, putting the article the in that tweet would make. Please really help me understand. I am really extremely confused!

P.S. Sorry to post yet another question alongside this topic. It’s still related, don't worry. ![]() This consciousness of English grammar and rules that recently sprung up within me has taken its toll on my speech and writing. Now, I’m having difficulty with using words I’ve used with so much ease before. The words “courage” and “time” are an example. In the sentences that follow, what is the difference between the sentences that have the indefinite article before the words courage and time, and those that occur without it?

This consciousness of English grammar and rules that recently sprung up within me has taken its toll on my speech and writing. Now, I’m having difficulty with using words I’ve used with so much ease before. The words “courage” and “time” are an example. In the sentences that follow, what is the difference between the sentences that have the indefinite article before the words courage and time, and those that occur without it?

“I don’t have THE courage to sing.”

“I don’t have courage to sing.”

“I don’t have THE time to get a haircut.”

“I don’t have time to get a haircut.”

I used not to worry about using these words before, sir. I just want to get my confidence back. Please help me.

My reply to English Maiden’s rejoinder:

To be thoroughly conversant with the usage of the articles “a,” “an,” and “the,” you need a full-dress review of the nature and kinds of nouns in the English language. You will recall that there are seven kinds of nouns: common nouns, proper nouns, collective nouns, abstract nouns, compound nouns, count nouns, and mass nouns. There are specific rules for indicating the indefiniteness, definiteness, specificity, and particularity of each of these kinds of nouns. Click this link to the eHow Family Education website (http://www.ehow.com/list_6520007_seven-kinds-nouns.html) for its nifty, short and sweet description of each of them.

For the usage of the articles in modifying nouns, click this link to the Purdue Online Writing Lab (http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/540/01/). It makes a comprehensive discussion of the usage of English articles depending on the sound that begins a particular noun, the choice of article for count and noncount (mass) nouns, and the types of nouns that don’t need to be preceded by articles. I’m sure that after studiously going over the discussions in those two websites, your confusion over the usage of articles will forever be a thing of the past.

As to this tweet that you have just posted, “My uncle has a weird habit of talking to and feeding lizards in his room,” it’s a grammar-perfect sentence. It correctly uses of the indefinite article “a” for the noun “habit” and correctly omits using any article before the noun phrase “lizards in his room” Had you written that sentence as “My uncle has a weird habit of talking to and feeding the lizards in his room,” it would have given the weird impression that he knows those lizards intimately and that he knows precisely which and how many of them are regular denizens of his room.

Without the article “the” before “lizard,” on the other hand, it would indicate that his relationship with those lizards hasn’t really gotten out of hand; he just enjoys feeding them regardless of whether or not he knows them intimately and whether they are regular denizens of his room or just strangers out to get a free meal.

From this, we can see how profound the impact of article usage is to the subjects or objects of our sentences and, even more important, to what it is precisely that we want to say in English.

I noticed just now that you’ve made a P.S. regarding your confusion over the article usage for the following sentences:

“I don’t have THE courage to sing.”

“I don’t have courage to sing.”

“I don’t have THE time to get a haircut.”

“I don’t have time to get a haircut.”

I’m sure that after going to the two websites I indicated earlier in this post, you’ll get your confidence back and find it a breeze figuring out which versions are correct in the sentence pairs you presented above.

Go for it and let me know what happens!

Rejoinder from English Maiden:

Thanks for that explanation, sir. It was really, really helpful. But I am afraid I still am not sure which of the sentences below are the correct ones. I’ll just take a guess. Sentences 1 and 4 are the ones that are correct. Please reply and tell me if I'm right or wrong. Thank you.

(1) “I don’t have THE courage to sing.”

(2) “I don’t have courage to sing.”

(3) “I don’t have THE time to get a haircut.”

(4) “I don’t have time to get a haircut.”

My reply to English Maiden’s rejoinder:

Sentence 1 is correct; Sentence 2 isn’t and sounds stilted as well.

Both Sentence 3 and Sentence 4 are correct. When the speaker uses the article “the,” he or she is referring to the specific length of time it takes to have that haircut; without the article “the,” he or she is referring to having a haircut in general, regardless of how long it might take. Be aware, though, that the difference is very slight and is often only in the speaker’s mind. The listener will probably not even notice that difference.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

When it’s a tough call whether a noun needs a definite article

Question by English Maiden, Forum member (November 25, 2011):

My question has to do with how to decide whether a noun or noun phrase modified by a prepositional phrase or relative clause should take definite article “the” or no article at all. In the sentences below, are the prepositional phrases and relative clauses modifying the nouns “definite” enough to take the article “the,” or is that article not needed or incorrect in these sentences? Or is that “the” optional, meaning that the sentence can work perfectly well with or without the indefinite article?

1. “Haters only hate THE things that they can’t get and THE people they can’t be.”

2. “Prevent me from knowing THE things that I don’t really have to know.”

3. “I will check out THE hot shopping spots in South Korea.”

4. “I hate THE people who don’t hold the elevator door open for you, no matter how loudly you say ‘Wait, I'll get in’.”

4. “What are THE things to consider when going abroad for a business trip?”

I’ve read each sentence aloud twice, first as written and second with the definite articles removed, and both versions of all five sentences seem correct to me. Is there really ever any difference? Please help to clear my mind.

P.S. Please add to my examples this sentence in the Facebook log-in page: “Facebook helps you share and connect with THE people in your life.” Is the modifying phrase “in your life” enough to make the noun “people” definite, hence to take the article “the”? To me, it’s not, because as a reader, I don’t know which “people in my life” the writer of that sentence is referring to. So, could it be that the correct way to write that sentence is by dropping the article “the,” as in “Facebook helps you share and connect with people in your life”?

My reply to English Maiden:

In all those five sentences of yours, the determining factor in whether to use the article “the” for the object noun phrases is the speaker’s or writer’s prior and specific knowledge or awareness of the fact or circumstance indicated or previous actual experience with the situation described. With that prior knowledge or awareness or previous experience, the article “the” is a must; the modifying phrase “in your life” alone isn’t enough to make the noun “people” definite. Without that prior knowledge or awareness or previous experience, the article “the” is unnecessary or optional to the sentence. Take a look at the two versions to see the semantic difference:

1. With “the”: “Haters only hate the things that they can’t get and the people they can’t be.”

Without “the”: “Haters only hate things that they can’t get and people they can’t be.”

2. With “the”: “Prevent me from knowing the things that I don’t really have to know.”

Without “the”: “Prevent me from knowing things that I don’t really have to know.”

3. With “the”: “I will check out the hot shopping spots in South Korea.”

Without “the”: “I will check out hot shopping spots in South Korea.”

4. With “the”: “I hate the people who don't hold the elevator door open for you, no matter how

loudly you say ‘Wait, I’ll get in.’”

Without “the”: “I hate people who don't hold the elevator door open for you, no matter how

loudly you say ‘Wait, I’ll get in.’”

5. With “the”: “What are the things to consider when going abroad for a business trip?”

Without “the”: “What are things to consider when going abroad for a business trip?”

In the case of the Facebook statement you quoted, the article “the” is absolutely needed for the phrase “people in your life,” as follows “Facebook helps you share and connect with the people in your life.” With that “the,” the reference is only to the important people in your life—the people that particularly matter to you. Without that “they,” the reference is to all the people you’ve associated or gotten in touch with in your life, no matter how trivial or inconsequential the association or contact. We can be sure that Facebook didn’t mean it this way, for it would mean connecting with practically all of the people who’ve figured in our life—a staggering number that could be in the tens or hundreds of thousands. Friending all of them would hideously overwhelm even an unabashedly mass-friending medium like Facebook.

Rejoinder by English Maiden (November 26, 2011):

Thanks again and again for your prompt answers to my grammar queries. I somehow understand what you mean, but I wouldn’t say I completely understand the hints you provided. Isn’t it that the only way a noun becomes definite in speech and in writing is if it is known to both the speaker/writer and the listener/reader? Suppose I tweet “I visited THE hot shopping spots in South Korea,” given that I have prior knowledge and experience of these shopping spots I’m pertaining to. But if I’m the only one who knows about the shopping spots I’m talking about in that tweet, wouldn’t it leave my readers or followers confused and guessing about which shopping places I’m referring to? And so on that note, would it be more appropriate not to use the article “the” at all?

My reply to English Maiden’s rejoinder:

At the outset, assuming that they are strangers to each other, the only thing commonly known between the speaker/writer and the listener/reader is language—how it works and the meanings that arise from the various combinations of its words. There is therefore no way for the listener/reader to know precisely what’s in the speaker’s/writer’s mind—in particular, whether a noun used is meant to be definite or indefinite—until he or she has written the statement to begin with.

Now, when you tweet “I visited THE hot shopping spots in South Korea,” the reader on Twitter obviously will perceive you as someone who wants to make the impression of being extremely knowledgeable about the hot shopping spots in South Korea, having presumably visited all or most of them. It makes no difference whether your reader knows everything or doesn’t know anything about those hot shopping spots, or whether you are just making a tall claim to begin with. And there need not be any confusion or guessing about that declaration of yours, because it’s not as if you made that statement ex cathedra—not subject to clarification or challenge like a papal edict. In fact, if the Twitter reader (who just might happen to be a well-informed Seoul resident) is interested at all in your tweet, he or she will likely tweet back: “Precisely which shopping spots are those? And how do you know they are ‘hot’?” Then a real conversation starts on Twitter wherein you’ll be obliged to support your contention that you have indeed “visited THE hot shopping spots in South Korea.” Since it’s highly improbable that you’ve visited all or most of those ‘hot’ shopping spots, you’d likely be forced to scale down your claim to, say, “Well, I actually visited only four of them in Seoul and I thought they were ‘hot’ because there were so many people in them…” Then you may get a follow-up tweet like, say, “Which four did you actually visit? And how big was the crowd in each of them during your visit?” And the Twitter conversation continues until the reader and you have clarified and exhausted the subject to your mutual satisfaction.

My point in the rather elaborate explanation above, English Maiden, is that you really shouldn’t put too much store in a single sentence or two as the be-all and end-all of communicating an idea—which I’m afraid is the communication culture that Twitter inadvertently promotes. Because of the 140-word limit to each tweet, the tweeter is constrained to give an unwarranted sense of factuality or finality to every tweet he or she makes. In a real-world conversation, however, everything said is at best tentative, subject to being qualified or modified for greater accuracy in the course of the conversation. There’s much less pressure for the speaker to overstate or exaggerate with a strong declarative statement like “I visited THE hot shopping spots in South Korea”; more likely, the norm for that opening statement will be the more unprepossessing and modest “I visited hot shopping spots in South Korea”—without the “the.” After all, there will be lots of room to qualify the statement to a level of accuracy closer to the truth. This level of qualification, however, is something that’s difficult to achieve in a medium like Twitter, which I think is much more suited to brief announcements rather than to discussions of complex ideas.

This being the case, for modesty’s sake as well as for semantic correctness, I think it would be more appropriate not to use the article “the” at all in that sample tweet of yours. A bare-bones “I visited hot shopping spots in South Korea” or a qualified “I visited a few hot shopping spots in South Korea” definitely will be much more advisable.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

The application and grammatical attribute of “whoever’s”

Question by Hairstyler, Forum member (November 24, 2011):

Please help me to describe the application and attribute of “whoever’s” in the follwing sentences:

1. “Whoever’s this is is to be returned.”

2. “The office is cleaned by whoever’s turn it is that day.”

My reply to Hairstyler:

The use of “whoever” in these two sentences you presented isn’t permissible at all:

1. “Whoever’s this is is to be returned.”

2. “The office is cleaned by whoever’s turn it is that day.”

The pronoun “whoever,” which means “whatever person—no matter who,” can be used in any grammatical relation except that of a possessive; that is the prescribed rule in English. This means Sentence #2 above is an inherently grammatically flawed construction, for the phrase “whoever’s turn it is that day” uses the disallowed possessive form “whoever’s.” Another serious flaw in Sentence #2 is that it makes the noun “turn” in “whoever’s turn it is that day” the doer of the action of the verb “cleaned.” This is not possible in reality, of course; in the context of that sentence, only a person can do that cleaning job. And even if we acknowledge Sentence #2 as possible colloquial usage, it needs to be recast to the following form to be grammatically acceptable: “The office is cleaned by whoever has the turn for that day.”

The use of “whoever’s” in Sentence #1 is likewise grammatically flawed because it uses the the disallowed possessive form “whoever’s.” Worse, the use of two successive “is’s” by that sentence is syntactically very clumsy. Here’s a possible rewrite that can salvage that sentence into acceptable form: “Whoever found this (“bag,” “purse,” “iPod,” whatever) has to return it to its owner.”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Do we use the article “a” or “they” for nouns preceded by “perfect”?

Question by English Maiden (November 27, 2011):

Sir, I’m not quite sure which kind of articles to use in the following sentences:

“My mother is (a/the) perfect mother.”

“This is (a/the) perfect time to go shopping.”

“These are (no article/the) perfect books to read in my free time.”

“We need to come up with (a/the) perfect backup plan.”

Please explain to me which article to use and why.

Also, why can we say or write “I had A FEAR of falling from high places when I was in high school” during the first mention of the noun FEAR or when we are establishing for the reader/listener the existence of such a fear, but not “I have AN ABILITY to spell my name backwards,” considering that the situation and intent are the same as those of the first sentence?

My reply to English Maiden:

All of the four “perfect”-using sentences you presented should use the article “the.” They are socially acceptable idiomatic overstatements that would lose their cogency if the article “a” or no article is used instead. So even if nothing’s perfect and you know in your heart that they are not exactly truthful, don’t hesitate to say those statements in the following manner:

“My mother is the perfect mother.”

“This is the perfect time to go shopping.”

“These are the perfect books to read in my free time.”

“We need to come up with the perfect backup plan.”

As to your question about the usage of the perfect tenses in the two sentences you presented, the difference between those sentences is as follows:

When you say “I had A FEAR of falling from high places when I was in high school,” you need to use the past perfect “had a fear” because based on that declaration of yours, that fear was a subsisting (continuing) condition during the time that you were in high school, and it can be inferred from that statement of yours that you no longer have that fear at present (today).

In contrast, when you say “I have AN ABILITY to spell my name backwards,” you need to use the present perfect “have an ability” because based on that declaration of yours, that ability to spell you name backwards has been a longstanding ability of yours that subsists up to the present. The present perfect is the tense that denotes that continuing condition.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

How gerunds function as subject complement

Question by hairstyler, Forum member (November 13, 2011):

Dear Carillo,

Please help me explain the function of the gerund as a subject complement in the following example:

(1) “What she is going through is called being in labor.”

Please help me clarify if the underlined word in the following sentences is a gerund or participle:

(2) “I saw him wearing a red shirt.”

(3) “I dislike him/his wearing a red shirt.”

My reply to hairstyler:

In Sentence #1, “What she is going through is called being in labor,” the gerund phrase “being in labor” is not a subject complement. It’s functioning as an adverbial modifier of the verb “called.” That gerund phrase will function as a subject complement if the verb “called” is dropped so the sentence will read as follows: “What she is going through is being in labor.” Here, “being in labor” is now a subject complement linked to the subject “what she is going through” (a relative noun clause) by the linking verb “is.”

In Sentence #2, “I saw him wearing a red shirt,” the word “wearing” is neither a gerund nor a participle. It’s the progressive form of the verb “wear,” indicating a continuing past action, and the phrase “wearing a red shirt” functions as an adjective phrase modifying the pronoun “him.”

In Sentence #3, using the pronoun “him” will make the sentence read as follows: “I dislike him wearing a red shirt.” Here, the word “wearing” is the progressive form of the verb “wear,” indicating a continuing past action as in Sentence #2 above; the phrase “wearing a red shirt” is an adjective phrase modifying the pronoun “him.” On the other hand, when the pronoun “his” is used, the sentence will read as follows: “I dislike his wearing a red shirt.” This time, the phrase “his wearing a red shirt” is a gerund phrase that functions as an adverbial modifier of the verb “dislike.”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Keeping up with “be” as a very versatile but highly irregular verb

Question from English Maiden, Forum member (November 6, 2011):

Hi, Sir! I have always wondered why the verb “be” (e.g., “is,” “was,” “were,” “am,” “been,” etc.) is called as such? I know that the verb “be” is used as an auxiliary verb and can also be used as a main verb, but I don’t understand why the forms of this verb are collectively known as “be.” Please shed some light on this matter for me. Thanks loads!

My reply to English Maiden:

The verb “be” happens to be one of the most versatile and most often used words in the English language. As you say, it’s used as an auxiliary verb and can also be used as a main verb, but it’s incorrect to call it the collective word for the various forms it takes in the language. It’s a unique word by itself that also happens to be a highly irregular verb—meaning that it doesn’t obey the usual conjugation rules for regular verbs but changes into altogether new words when doing particular grammar tasks. In particular, as an intransitive verb, “be” has so many denotations or meanings and takes on different forms; as a verbal auxiliary, it has four distinct uses in the formation of the various tenses of verbs, also taking on different forms and even working with other verbal auxiliaries to evoke a specific tense and sense for a verb. You can appreciate how versatile and hardworking “be” is by going over the definitions below that I have excerpted from the Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary.

Having clarified the nature and functions of “be,” I can now tell you that the various forms of “be” that you mentioned—“is,” “was,” “were,” “am,” “been”—are not its collective in the true sense of that word. They are just inflections of “be,” or the changes in form that “be” undergoes to mark the case, gender, number, tense, person, mood, or voice of the sentence where it is used. As such, they are unique words in themselves, distinct from “be” and each with a specific functional role in the language.

be

intransitive verb

1 a : to equal in meaning : have the same connotation as : SYMBOLIZE <God is love> <January is the first month> <let x be 10> b : to have identity with <the first person I met was my brother> c : to constitute the same class as d : to have a specified qualification or characterization <the leaves are green> e : to belong to the class of <the fish is a trout> — used regularly in senses 1a through 1e as the copula of simple predication

2 a : to have an objective existence : have reality or actuality : LIVE <I think, therefore I am> <once upon a time there was a knight> b : to have, maintain, or occupy a place, situation, or position <the book is on the table> c : to remain unmolested, undisturbed, or uninterrupted — used only in infinitive form <let him be> d : to take place : OCCUR <the concert was last night> e : to come or go <has already been and gone> <has never been to the circus> f archaic : BELONG, BEFALL

verbal auxiliary

1 — used with the past participle of transitive verbs as a passive-voice auxiliary <the money was found> <the house is being built>

2 — used as the auxiliary of the present participle in progressive tenses expressing continuous action <he is reading> <I have been sleeping>

3 — used with the past participle of some intransitive verbs as an auxiliary forming archaic perfect tenses <Christ is risen from the dead — 1 Corinthians 15:20(Douay Version)>

4 — used with the infinitive with to to express futurity, arrangement in advance, or obligation <I am to interview him today> <she was to become famous>

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

How the predicted future differs from the simple future tense

Question by English Maiden, Forum member (November 4, 2011):

Hi, Joe!

I hope this is not asking for too much, but could you please explain in detail the differences in the use of the forms “will + the base form” and “be going to + the base form” when making reference to the future. I have consulted several English grammar books, but I still find myself confused. For example, I can't seem to tell the difference in meaning, if any, between the following sentence pairs:

“I am going to/gonna forget about you someday.”

“I will forget about you someday.”

“I am going to/gonna be a recording artist someday.”

“I will be a recording artist someday.”

“I’m going to/gonna watch a movie with friends tonight.”

“I will see a movie with friends tonight.”

I can cite more examples, like lines from songs and movies you know. Please help me understand. Thank you in advance.

My reply to English Maiden:

We learn early in grammar school that in English, verbs have the handicap of not being able to inflect or morph by themselves into the future tense. To compensate for this, however, English came up with no less than six ways of evoking the future, as follows:

(1) The simple future tense, which puts the auxiliary verb “will” ahead of the verb stem, as in “will take” in “The chairman will take his retirement next month,” and

(2) The future perfect tense, which uses the so-called temporal indicators to situate actions and events in various times in the future, as in the use of the future perfect “will have taken” in “By this time next month, the chairman will have taken his retirement.”

In both cases, instead of inflecting itself, the verb “take” took the expedient of harnessing one verb (“will”) or two auxiliary verbs (“will have”), respectively, to make its two visions of the future work.

Then English came up with four more grammatical stratagems to evoke the future tense, as follows:

(3) The arranged future, also known as the present continuous;

(4) The predicted future;

(5) The timetable future, also known as the present simple; and

(6) The described futures, also known as the future continuous.

The future-tense type that you say confuses you—the one that uses the form “be going to + the verb’s base form”—is Form #4 above, the predicted future. As in the first example you have given, “I am going to forget about you someday,” this form of the future tense uses the verb’s infinitive form preceded by the auxiliary phrase “going to.” It serves as a categorical forecast of what will happen based on what the speaker knows about the evolving present. (The alternative sentence you provided, “I am gonna forget about you someday,” uses “gonna,” which, of course, is a colloquial contraction of “going to.”)

So how does the predicted future form differ from the simple future form below that uses “will forget”?

“I will forget about you someday.”

The difference is that the simple-future form using “will” simply states that something will happen in the future, while the predicted-future form using “going to” categorically declares that the speaker will make a purposive effort to make the stated future outcome happen.

There are two other uses of the “going to” future-tense form:

(1) To express what people want to do, as in “I’m going to think over your suggestion.” This form of the purposive future suggests that the speaker had thought about the action before speaking about it, as opposed to deciding on it spontaneously, in which case the simple future tense using “will” is more appropriate: “I will think over your suggestion.”

(2) To express something that the speaker believes is impossible to avoid or prevent: “You know that the circus is going to close this Friday.”

Statements in the predicted future form are shaped both by the information the speaker has about that future and how he or she wants that future to be. They can use a temporal indicator (as “someday” in your example) but don’t necessarily require it, as in “I am going to forget about you.” When precise time frames are provided, the simple future tense is often preferable: “I will forget about you someday.”

For a better understanding of the “be going to” form of the future tense, I am posting in this week’s edition of the Forum “The Six Ways That English Reckons with the Future.” That essay introduces Section 7 – “Mastering the English Tenses” of my book Give Your English the Winning Edge. The nine chapters in that section of the book provide an intensive discussion of the various future-tense forms in English and the usage of the adverbs of time.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

“Stabbed dead” or “stabbed to death?”

Forum member ooliveros e-mailed the news alert below last November 2, 2011 along with this question:

“Stabbed dead” or “stabbed to death?”

Charice Pempengco’s father stabbed dead after drinking session

Victim, ‘killer’ both drunk, say investigators

CAMP PACIANO RIZAL, Laguna – The estranged father of international singing sensation Charice Pempengco was stabbed dead in San Pedro, Laguna before midnight Monday, police said on Tuesday...

My reply to ooliveros:

Saying it either way is acceptable journalistic usage: “stabbed dead” or “stabbed to death.” Both are widely used idioms for “Died after being stabbed” in much the same way as “shot dead” or “shot to death” are used for “Died after being shot.”

As in your case, of course, what uncomfortably comes to my mind from reading or hearing “stabbed dead” is that the victim was “stabbed when already dead” (how macabre!) or that the assailant “kept on stabbing the victim until he or she died” (how gruesome!). For a long time now, though, these haven't been the intended senses for “stabbed dead” or “stabbed to death,” as evidenced by the following comparative Google hits of their usage in the sense of “Died after being stabbed”:

“Stabbed dead” – 185,000

“Stabbed to death” – 12,900,000

The comparative Google hits for their counterpart “death by shooting” idioms are as follows:

“Shot dead” – 14,000,000

“Shot to death” – 13,800,000

This preponderance of “stabbed/shot dead” and “stabbed/shot to death” usage should dispel once and for all our lingering doubts about their grammatical and semantic validity.

In English as in most languages, usage trumps logic over the long haul.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Checking “sandwich generation” as a brand-new dictionary entry

Question by VrackGrl27, new Forum member (October 30, 2011):

Hello ,

There are lots of new words coming in today in the Webster Dictionary and just as recently the word “sandwich generation” came in under Miscellaneous. What does this mean exactly? And can you please show me an example as to how to use this properly in a sentence? Thank you.

My reply to VrackGrl27:

It’s my first time to hear the term “sandwich generation,” having lived all my life in a part in the world where it’s rarely written about or heard, so I decided to do some quick research. It turns out that The Sandwich Generation—a proper noun—stands for “a generation of people who care for their aging parents while supporting their own children.” This definition is from “The Sandwich Generation,” the personal website of Carol Abaya who describes herself as a nationally recognized expert on the subject as well as on aging and elder/parent care issues.

The Abaya website says that the term “sandwich generation” was added to Merriam-Webster in July 2006; it’s not to be found in my Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary, which, alas, turns out to have been published in 2003 or about three years before Ms. Abaya coined the term. The online Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary does have an entry defining “sandwich generation” exactly as in Ms. Abaya’s website, and noting that the term had its first known use in 1987.

At any rate, here’s something that should enlighten everybody about what the “sandwich generation” is all about. Ms. Abaya classifies those falling under the sandwich generation as follows:

(1) Traditional: those sandwiched between aging parents who need care and/or help and their own children.

(2) Club Sandwich: those in their 50s or 60s sandwiched between aging parents, adult children and grandchildren, or those in their 30s and 40s, with young children, aging parents and grandparents.

(3) Open Faced: anyone else involved in elder care.

So, as you requested, VrackGrl27, I’m now in a pretty good position to use the term properly in a sentence. Here goes:

“I learned today that by age, I should by rights now be a fully qualified member of the Sandwich Generation, but also that I’m unclassifiable as a Club Sandwich because I’m not in the ‘50s or 60s sandwiched between aging parents, adult children and grandchildren’ nor in the ‘30s and 40s, with young children, aging parents and grandparents.’ Neither am I a Traditional because I’m not ‘sandwiched between aging parents who need care and/or help and their own children,’ nor Open Faced because I’m not ‘involved in elder care.’”

Well, by that analysis, it turns out that under the definition of the Sandwich Generation, I was a briefly a member of it two or so decades ago, but not anymore by a twist of fate and demographics!

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

The problem with faulty and unparallel phrase constructions

Question by roylic, Forum member (October 23, 2011):

Hi, Joe,

I’m having problem reconciling these two phrases: “to harvest knowledge” and “to being educated.” If I understand correctly, “to harvest” is an infinitive, and “to being” is a gerund. Can you use them in one sentence? Is it being consistent?

Here is the original text:

“Last but not least I wish to say that the purpose of university is to harvest knowledge and to being educated, so it is obvious that everyone can find a reason for attending university.”

Thank you.

My reply to roylic:

You’re having a problem reconciling those phrases because the construction of that sentence is grammatically and semantically faulty:

“Last but not least I wish to say that the purpose of university is to harvest knowledge and to being educated, so it is obvious that everyone can find a reason for attending university.”

The first fault of that sentence is that it compounds two grammatical elements in different voices; this results in the sense of inconsistency you noted in that sentence. The first infinitive phrase, “to harvest knowledge,” is in the active voice with the noun phrase “the purpose of the university” as subject, while the second infinitive phrase, “to being educated,” is in the passive voice with the same noun phrase as subject. This second infinitive phrase is semantically faulty because it doesn’t make sense to say that “the purpose of the university” is “to being educated.” A university doesn’t seek to be educated; rather, it aims to educate. So the correct way to say this is “the purpose of the university is to educate,” with “educate” in the active voice and the noun “university” as the doer of the action.

The second fault of that sentence is its confusing unparallel construction, putting in a series two grammar elements of different structures. The parallelism rule provides that you can compound or add up two or more grammatical elements in a series only if they are of the same grammatical structure—whether all nouns, pronouns all in the same case, all gerund forms, all infinitive forms, all participial phrases, or all clauses in the same voice, etc. (Click this link to this forum posting, “Lesson #11 – Using Parallelism for Clarity and Cohesion,” for a comprehensive discussion of parallelism.”)

Taking all of the above considerations into account, that sentence you presented should therefore be grammatically corrected and its serial infinitive phrases made parallel, as follows:

“Last but not least I wish to say that the purpose of university is to harvest knowledge and to educate, so it is obvious that everyone can find a reason for attending university.”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Why are subject complements introduced or not introduced by “as”

Question by hairstyler, Forum member (October 20, 2011):

Dear Carillo,

(1) “The accident was reported as having been caused by carelessness.”

(2) “She was seen bringing her son in the car.”

Please help me describe the above-mentioned sentences, particularly why in the first sentence, the subject complement is introduced by “as,” and why in the second sentence, the complement is not introduced by “as.”

Thanks a million,

Hairstyler

My reply to hairstyler:

Here’s my grammar take on the two sentences you presented:

(1) “The accident was reported as having been caused by carelessness.”

In the sentence above, the phrase “having been caused by carelessness” is introduced by the adverb “as” so that phrase can function as an adverbial modifier of the verb “reported,” describing the cause of the subject “accident.” When the adverb “as” is used before a participial phrase (“having been caused by carelessness” in this case), it conveys the sense of “when considered in the relation or form” specified by that participial phrase. This is precisely the sense of the sentence in question here.

(2) “She was seen bringing her son in the car.”

In the sentence above, the phrase “bringing her son in the car” is not introduced by the adverb “as” because it functions as an adjective complement in that sentence. It modifies not the passive verb form “was seen” but the subject “she.”

To understand why this is so, think of that sentence in the active voice: “I saw her bringing her son in the car.” In this form, it’s very clear that the phrase “bringing her son in the car” doesn’t modify the verb but its object “her.” Putting the sentence in the passive voice doesn’t change that function of that phrase as an adjective complement.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Rare use of the function word “that”

Question by Hairstyler, Forum member (October 5, 2011):

I have never encountered the following usage of “that”:

“Who that you have ever seen can do better?”

Please help me describe the function of “that” in that sentence.

Thanks a million,

Hairstyler

My reply to Hairstyler:

I don’t think the sentence you presented is constructed properly:

“Who that you have ever seen can do better?”

That sentence has faulty syntax, its construction is stilted, and its use of “that” as a relative pronoun is dysfunctional. In fact, that usage of “that” isn’t only rare; it isn’t a grammatically valid usage at all.

Here are four ways of constructing that sentence correctly:

“Who have you seen can do better?”

“Who among those you have seen can do better?”

“Have you ever seen someone who can do better?”

“Have you ever seen anybody who can do better?”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Figuring out an odd usage of the function word “that”

Question from Hairstyler, Forum member (October 2, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

Firstly, thanks a million again and again, for you always help me solve different English problems without asking for a consultation fee.

Now, according to what I know about English, the function of “that” is to introduce an adjective clause. But in the two sentences below, please tell me what “that” is doing grammatically:

(1) “He is no longer the simple-minded man that he was five years ago.”

(2) “What he said and did there showed the man that he was.”

Up to now, I really don’t know the function of “that” in those sentences.

Thanks,

Hairstyler

My reply to Hairstyler:

You are correct in saying that the function of “that” is to introduce an adjective clause. This is the case in a sentence like “She made me believe that life is but a dream.” Here, “that” functions as a subordinating conjunction to introduce the modifying adjective clause “life is but a dream” and link it to the main clause, “she made me believe.” But this is not the only function of “that” in English grammar. In fact, as I’m sure you’ll recall, “that” can even function also as a pronoun, adjective, and adverb.

But in relation to your question, let’s just focus on the various functions of “that” as a conjunction. My Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary lists down as many as 10 functions of “that,” as follows:

1 a (1) — used as a function word to introduce a noun clause that is usually the subject or object of a verb or a predicate nominative <said that he was afraid> (2) — used as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause that is anticipated by the expletive it occurring as subject of the verb <it is unlikely that he’ll be in> (3) — used as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause that is joined as complement to a noun or adjective <we are certain that this is true> <the fact that you are here> (4) — used as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause modifying an adverb or adverbial expression <will go anywhere that he is invited> b — used as a function word to introduce an exclamatory clause expressing a strong emotion especially of surprise, sorrow, or indignation <that it should come to this!>

2 a (1) — used as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause expressing purpose or desired result <cutting down expenses that her son might inherit an unencumbered estate — W. B. Yeats> (2) — used as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause expressing a reason or cause <rejoice that you are lightened of a load — Robert Browning> (3) — used as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause expressing consequence, result, or effect <are of sufficient importance that they cannot be neglected — Hannah Wormington> b — used as a function word to introduce an exclamatory clause expressing a wish <oh, that he would come>

3 — used as a function word after a subordinating conjunction without modifying its meaning <if that thy bent of love be honorable — Shakespeare>

You can see from the above functions of “that” that the usage in the two sentences you presented falls under Definition 1a (3), “as a function word to introduce a subordinate clause that is joined as complement to a noun or adjective.”

Now let’s take a close look at your two sentences:

(1) “He is no longer the simple-minded man that he was five years ago.”

(2) “What he said and did there showed the man that he was.”

In Sentence 1, the conjunction “that” introduces the subordinate clause “he was five years ago” as a complement to the noun “man” in the main clause. The intended meaning is, of course, that the man was simple-minded five years ago but is no longer simple-minded now.

Similarly, in Sentence 2, the conjunction “that” introduces the subordinate clause “he was” as a complement to the noun “man” in the main clause. In that sentence, the intended meaning is that the man’s action in the particular place referred to in the main clause showed what kind of man that person was.

The usage of “that” in those two sentences is really as simple as that.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

When a modifying phrase must drop its verb to work properly

Question by hairstyler, Forum member (September 18, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

Please help me distinguish the difference between the following sentences:

(1) “The old man sat in the sofa, his face being serious.”

(2) “The old man sat in the sofa, his face is serious.”

Thanks.

My reply to hairstyler:

Both of the sentences you presented are grammatically flawed:

Let’s analyze the first one:

“The old man sat in the sofa, his face being serious.”

The modifying phrase “his face being serious” is grammatically dysfunctional because of the presence of the verb “being.” It should be dropped to make that phrase work properly, as follows:

“The old man sat in the sofa, his face serious.”

(The sentence works properly without the verb “being” in the modifying phrase “his face being serious.)

The second sentence you presented is likewise grammatically dysfunctional because of the presence of the verb “is.” As in the case of the verb “being” in the first sentence, it should also be dropped for that phrase to work properly, as follows:

“The old man sat in the sofa, his face serious.”

(The sentence works properly without the verb “is” in the modifying phrase “his face is serious.)

The two modifying phrases above whose operative verbs were taken out are known as absolute phrases or nominative absolutes. Unlike the usual modifying phrase, an absolute phrase doesn’t directly modify a specific word in the main clause of the sentence. Instead, it typically modifies the entire main clause, adding information or providing context to it.

In particular, the absolute phrase “his face serious” in the two corrected sentences above belongs to the most common form of the absolute phrase. In that form, a modifying word or phrase is tacked on to a noun or pronoun without using a verb, preposition, or conjunction, as in these examples: “His resolve weaker, the boxer gave up the fight.” “Its headlamps dim, the car rammed the lamppost.” This form of the absolute phrase can even be a single word (either a past participle or a present participle), as in these examples: “Miffed, the unwilling candidate snubbed his own proclamation.” “Wavering, the troops finally raised the white flag.”

Notice that the four sentences above that are modified by absolute phrases are actually elliptical or streamlined forms of the following sentences that are modified by participial or adverbial phrases: “The resolve of the boxer was weaker, so he gave up the fight.” “Its headlamps were dim, so the car rammed the lamppost.” “The unwilling candidate was miffed, so he snubbed his own proclamation.” “With them wavering, the troops finally raised the white flag.” By using absolute phrases as modifiers, the four sentences are able to get rid of the weak verb forms “was” and “were” and become simpler and more concise sentences.

I trust that this explanation adequately answers your question about the two grammatically flawed sentences you presented. For a more comprehensive discussion of the absolute phrases, I suggest you check out my book Give Your English the Winning Edge (Manila Times Publishing, 486 pages). It devotes three chapters to explain the intricacies of this admittedly baffling aspect of English grammar.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Some more puzzling Victorian English sentence patterns

Further questions from Hairstyler, Forum member (August 26, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

I don’t understand the sentence pattern below; please help me solve it. Thanks a million.

(1) “An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post.”

I don’t understand the reason why the above sentence has two “is” simultaneously and the subordinate clause haven’t a verb. Is it a special structure? Please state.

(2) “For guesses and doubts about the extent of his talents arouse more veneration than accurate knowledge of them, be they ever so great.”

I studied the “more ... than...” structure sometime ago, but I don’t know if a noun applied between the “more ... than…” is correct. Please explain if inversion occurs in the subordinate clause.

(3) “No one must know the extent of a wise person’s abilities, lest he be disappointed.”

I don’t understand whey subordinate clause use the verb “be” after the noun “he.”

Thanks you a million.

My reply to Hairstyler:

(1)

I’m not surprised that you find the following sentence difficult to understand:

An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post.

It’s because it has an abstruse construction that makes it almost a fused or run-on sentence (“Fused sentences are very serious and annoying grammar violations”), and one that’s made more confusing by inadequate punctuation. This also explains why, as you pointed out, that sentence appears to be using the linking verb “is” simultaneously for no grammatically valid reason.

The first step to unraveling that sentence grammatically is to recognize that its first clause, “an ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness,” is meant to be some rule being quoted verbatim. As such, that whole clause should be set off by a pair of quotation marks to make it a grammatically legitimate part of that sentence, as follows:

An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness” is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post.

We can see that when that quoted statement is set off by the pair of quotation marks, it becomes a noun form that serves as the subject of the main clause whose predicate is “the first and highest rule of all deeds and words.” In short, from a sentence structure standpoint, there’s actually only one linking verb “is” in that main clause—the one that links that quoted statement to the predicate of the main clause. Structurally, the other “is” doesn’t count because it’s integral to the quoted statement that’s functioning as the grammatical subject of that clause.

Now, these words that follow the first clause of that sentence in question may look like a subordinate clause but it really isn’t: “the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post. It’s actually a coordinate clause of the first clause, and together they form a compound sentence that normally would read as follows:

An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness” is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, and the higher and more numerous your posts, the more it will be necessary to follow that rule.

However, to make the statement more concise and punchy, not only was the second coordinate clause inverted but it was also reduced or ellipted—some words were dropped from it, including the coordinating conjunction “and” and the linking verb form “to be”—as follows:

An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness” is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, [and] the more necessary [it has to be] to be followed the higher and more numerous your posts.

For an explanation of how ellipses work, click this link to “Understanding the advanced grammar of elliptical sentences.”

(2)

Yes, a noun applied between the comparative “more ... than” is grammatically correct, as in the case of “veneration” in this sentence you presented:

For guesses and doubts about the extent of his talents arouse more veneration than accurate knowledge of them, be they ever so great.

The comparison being made is, of course, between two subjects, “veneration” and “accurate knowledge of (the extent of his talents).” But I don’t think inversion has been done to that sentence. What happened is simply that the adverbial modifier “be they ever so great” was moved to the tail end of the sentence for greater impact. The normal position of that adverbial modifier is as follows:

For guesses and doubts about the extent of his talents, be they ever so great, arouse more veneration than accurate knowledge of them.

(3)

Regarding the use of the verb “be” after the noun “he” in the following sentence:

“No one must know the extent of a wise person’s abilities, lest he be disappointed.”

The word “lest” is being used in that sentence as a subordinating conjunction that means “so as to prevent any possibility, and “lest” is a subordinating conjunction that requires that particular clause to be in the subjunctive mood, which in turn is a form that requires the linking verb “is” to always take the subjunctive form “be” regardless of whether the subject is singular or plural (“The proper use of the English subjunctive”).

POSTSCRIPT:

I have determined that the three quotations submitted by Hairstyler for deconstruction are also from the Oraculo manual y arte de prudencia (The Art of Worldly Wisdom), written in 1637 by the Spanish-born Jesuit priest Balthasar Gracian (1601-1658) and translated into English by the Australia-born British folklorist and literary critic Joseph Jacobs in 1892. This is the same source of samples of Victorian English sentence patterns that Hairstyler earlier posted in the forum for deconstruction.

I must say for the record, though, that Hairstyler disingenuously fudged Gracian’s Aphorism 92—the quoted statement in Item #1 above—when he submitted it for deconstruction. Its exact wording in the Jacobs translation is as follows:

xcii Transcendant Wisdom.

I mean in everything. The first and highest rule of all deed and speech, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous our posts, is: an ounce of wisdom is worth more than tons of cleverness. It is the only sure way, though it may not gain so much applause. The reputation of wisdom is the last triumph of fame. It is enough if you satisfy the wise, for their judgment is the touchstone of true success.

In other words, Hairstyler took extreme grammatical liberties with Gracian’s ideas in that aphorism and with the text of Joseph Jacob’s translation of it—something that’s very unseemly from someone who had presented himself as a serious student of English needing help in his self-improvement efforts. Sad to say, at least in the case of Gracian’s Aphorism 92, Hairstyler deliberately created even more serious grammatical complications than the original already had, thus wasting not only my time and effort but also those of Forum members following the discussion thread. It appears now that Hairstyler was more interested in putting my English sentence deconstruction skills to a test rather than in truthfully seeking understanding of the peculiar grammar of the original passage.

Even under these circumstances, though, I stand by my detailed deconstruction above of Gracian’s Aphorism 92 as rewritten by Hairstyler. But I must warn Hairstyler that the underhanded practice of fudging original passages in the literature for grammatical deconstruction in the Forum is unwelcome and will be dealt with severely the next time it’s done.

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

When English doesn’t seem to use the English grammar we know

Further questions from Hairstyler, Forum member (August 29, 2011):

Firstly, thank you for your help again. I really don’t know how to thank you. Again and again, thanks a million!

(1) “It is preposterous to take to heart that which you should just throw over your shoulders.”

I know the sentence structure “it is +adj.+ for + N + to + V,” but not what the word “which” represents and why “that” is positioned before “which.” Please explain.

(2) “Much that would be something has become nothing by being left alone, and what was nothing has become of consequence by being made much of.”

Please help me by explaining why the word “being” is positioned before “left alone” and “made much of.”

Do they belong to the category of adjective attribute, so we need to add “being” before them to make them a noun attribute? Please clarify.

My reply to Hairstyler:

I was wondering why you were coming up with so many abstruse and convoluted English sentences—people don’t talk or write English like that anymore—so I was tempted to check where you were getting all of them. I wasn’t surprised when I found out that the two latest puzzling sentence constructions you posted in the Forum are from a Victorian English translation of a book written originally in Spanish. They are from Oraculo manual y arte de prudencia (The Art of Worldly Wisdom), written in 1637 by the Spanish-born Jesuit priest Balthasar Gracian (1601-1658) and translated into English by the Australia-born British folklorist and literary critic Joseph Jacobs in 1892.

I am raising these points not to question the grammatical and structural integrity of the two hard-to-understand sentences that I’m now about to deconstruct here. It’s simply that those two aphorisms—which, of course, are concise, pithy formulations of someone’s sentiment or perception of the truth—used the peculiar English syntax of a bygone era in an attempt to faithfully capture the flavor and cadence of ideas expressed in the linguistically more difficult Spanish tongue. So, if those sentences sound inscrutable to you, it’s not necessarily because your English isn’t good enough. It’s just that the English of those sentences is too arcane and too convoluted to the modern mind and ear—even to native English speakers, I dare say.

Now let’s deconstruct the first sentence that baffles you:

“It is preposterous to take to heart that which you should just throw over your shoulders.”

First, we must recognize that the sentence above is a complex sentence consisting of two clauses, as follows:

1. Main clause: “It is preposterous to take to heart (something)”

2. Subordinate clause: “(It is) something you should just throw over your shoulders”

These two clauses are then linked and combined into a complex sentence by the subordinating conjunction “that,” as follows:

“It is preposterous to take to heart something that you should just throw over your shoulders.”

The peculiar syntax of Victorian English—and also perhaps the lilt of the original Spanish sentence—evidently demanded the removal of the word “something” because it detracted from the aphoristic quality of the statement. In its place, the English translator (Joseph Jacobs) decided to use the less obtrusive, indeterminate pronoun “which” instead of the word “something.” Structurally, however, the pronoun “which” would work properly only if positioned after the subordinating conjunction “that.” Indeed, in that position, “which” becomes not only the subject of the subordinate clause but the object of the main clause as well, as follows:

“It is preposterous to take to heart that which you should just throw over your shoulders.”

This appears to be how Joseph Jacobs’ Victorian English mind handled the translation of Balthasar Gracian’s aphorism in the original Spanish. In modern-day English, however, I think a simpler, more easily understood rendering of that aphorism would be the following:

“If you find something preposterous to take to heart, just throw it over your shoulders.”

A nonchalant, less prepossessing expression of that idea—meaning not aphoristic at all—would be this:

“Just throw over your shoulders what you find preposterous to take seriously.”

Now as to the second aphorism by Gracian as translated into English by Jacobs:

“Much that would be something has become nothing by being left alone, and what was nothing has become of consequence by being made much of.”

This is a tougher, even more convoluted form of Victorian English—a jigsaw-puzzle-type language that we don’t hear or see the likes anymore in modern discourse. I’ll offer a simpler rendering of that aphorism in modern English in a little while, but in the meantime, let me answer your question about its use of the word “being” twice in the same sentence.

Yes, I suppose you can say that “being” was added to each of the phrases “left alone” and “made much of” to make them acquire the attribute of nouns, but a simpler grammatical interpretation of the process is that the addition of “being” was meant to turn those adjective phrases into gerund phrases, which as you know function as nouns in sentences—whether as subject, object, or object of the preposition. The presence of the preposition “by” before the gerund phrases “being left alone” and “being made much of,” in turn, clearly indicates that those gerund phrases are functioning as objects of the preposition in their respective clauses.

Since it appears that you perfectly understood what that aphorism says despite its extremely convoluted form, I won’t attempt to explain its structure anymore beyond saying that the construction is that of a compound sentence consisting of two coordinate clauses joined by the coordinating conjunction “and.” I’ll just present what I think would be its modern English equivalent:

“Many consequential things turn to nothing when left alone, and some inconsequential things become consequential when we give too much importance to them.”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Is “self-explaining” proper usage or should it be “self-explanatory”?

Question from afridi4455, new Forum member (August 27, 2011):

Is it proper to use the word “self-explaining” when you are referring to an attached letter? e.g. “Please find attached self-explaining letter for your information and action.” While in other letters, it is written like this: “Please find attached letter for your information, which is self-explanatory.” Or is there a more appropriate way to say this?

Thanks and best regards.

My reply to afridi4455:

No, I don’t think “self-explaining” is a very apt word choice for referring to a letter attached to a transmission or forwarding message. Much more appropriate and widely used is the word “self-explanatory,” which means “explaining itself” or “capable of being understood without explanation.” In any case, the sample sentences you provided that use “self-explaining” and “self-explanatory” are wordy and stuffy bureaucratic clichés, and I really wouldn’t recommend their use. Specifically, I find the phrases “for your information and action” and “for your information objectionable because they state what’s already very obvious—for indeed, what else is a letter designed for but to inform somebody and make that somebody act on that information? It actually insults the intelligence of the receiver of the letter! So I would suggest this much simpler version instead:

“Please find the attached self-explanatory letter.”

Click to read responses or post a response

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)

Making sense of the perplexing grammar of elliptical sentences

Questions by Pedestrian, Forum member (August 18, 2011):

Hi, Jose,

Recently, I read some passages in which there are some straight sentences, as shown below:

(1) “Some make much of what matters little and little of much, always weighting on the wrong scale.”

My comment:

(a) In the second half sentence, “weighting” is used of “weight.” If so, there is no verb there. Then this second half is incorrect grammar, right?

(b) In the first half sentence, this is the first time for me to see this “little and little of much.” Could you tell me how to use it?

(c) Is it necessary to use a semicolon instead of a comma?

(2) “I prefer to going to lunch at 12:00p.m. than at 1:00 p.m.”

My comment: