- HOME

- INTRO TO THE FORUM

- USE AND MISUSE

- BADLY WRITTEN, BADLY SPOKEN

- GETTING

TO KNOW ENGLISH - PREPARING FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TESTS

- GOING DEEPER INTO ENGLISH

- YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

- EDUCATION AND TEACHING FORUM

- ADVICE AND DISSENT

- MY MEDIA ENGLISH WATCH

- STUDENTS' SOUNDING BOARD

- LANGUAGE HUMOR AT ITS FINEST

- THE LOUNGE

- NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

- ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

- Long Noun Forms Make Sentences Exasperatingly Difficult To Grasp

- Good Conversationalists Phrase Their Tag Questions With Finesse

- The Pronoun “None” Can Mean Either “Not One” Or “Not Any”

- A Rather Curious State Of Affairs In The Grammar Of “Do”-Questions

- Why I Consistently Use The Serial Comma

- Misuse Of “Lie” And “Lay” Punctures Many Writers’ Command Of English

- ABOUT JOSE CARILLO

- READINGS ABOUT LANGUAGE

- TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

- NEWS AND COMMENTARY

- BOOKSHOP

- ARCHIVES

Click here to recommend us!

USE AND MISUSE

The Use and Misuse section is open to all Forum members for discussing anything related to English grammar and usage. It invites and encourages questions and in-depth discussions about any aspect of English, from vocabulary and syntax to sentence structure and idiomatic expressions. It is, of course, also the perfect place for relating interesting experiences or encounters with English use and misuse at work, in school, or in the mass media.

Using commas or double dashes for punctuating parentheticals

Question by Miss Mae, Forum member (August 24, 2011):

Sir, in your discussion about parenthesis (Part I – “A unified approach to the proper use of punctuation in English”, Part II – “A unified approach to the proper use of punctuation in English”, Part III – “A unified approach to the proper use of punctuation in English”), I had deduced that I should only use double dashes if the parenthetical folds another sentence into a sentence or if a stronger break is needed. You also mentioned that “parentheticals enclosed by parentheses need not to be complete sentences.” Do you mean to say that parentheticals enclosed by commas or double dashes have to? Also, if parentheticals can behave as either modifiers, intensifiers, interrupters, or interjections, does it mean liberty for writers to place parentheticals where they want to?

My reply to Miss Mae:

Yes, parentheticals enclosed by parentheses need not be complete sentences. For instance, “The hospital nurse told her manager that she was sick (a lie) and stayed at a hospital for two days (a half-truth because she actually worked there part-time).” Here, of course, “a lie” is a noun phrase and “a half-truth because she actually worked part-time” is a sentence fragment.

Parentheticals enclosed by commas or double dashes likewise need not be complete sentences. Those enclosed by commas are often appositives, as in “The lady legislator, a tough-talking critic of government excess, called the government press official a spoiled brat,” or adjective phrases, as in “The French poet, legendary for his revolutionary poetry in his late teens, abandoned poetry altogether by the time he was 21.”

When the syntax of appositives and adjective phrases becomes more complicated than simple phrases, it becomes advisable to set them off with double dashes to avoid confusing the reader, as in the following example: “The lady legislator—a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form—called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.” Using double dashes to set off such parentheticals makes them more emphatic. However, even just setting off such complicated parentheticals with a pair of commas often will still do: “The lady legislator, a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form, called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.”

When the parenthetical is a complete sentence, however, it becomes grammatically mandatory to use a pair of double dashes, as in this example: “The lady legislator—she is a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form—called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.” To use only a pair of commas to set off complete-sentence parentheticals results in a run-on or fused sentence of the comma-splice variety: “The lady legislator, she is a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form, called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.”

One question remains, of course: Will parenthesis do for such complete-sentence parentheticals? The answer is not very well from the standpoint of syntax, as we can see in this construction: “The lady legislator (she is a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form) called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.” It will be much better to convert the parenthetical sentence into an adjective phrase, as follows: “The lady legislator (a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form) called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.”

Take note, though, that using parenthesis to set off such parentheticals diminishes their importance to the statement, making them sound simply as an aside that the writer or speaker doesn’t really consider important. It’s much better to use a pair of commas—but remember, they are not as good as double dashes—to set them off from the sentence: “The lady legislator, a tough-talking critic of government excess who won’t abide official insolence in any form, called the government press official a spoiled brat during a committee hearing.”

Click to read comments or post a comment

Deconstructing some perplexing sentence patterns

Questions by hairstyler, Forum member (August 26, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

I don’t understand the sentence pattern below; please help me solve it. Thanks a million.

(1) “An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post.”

I don’t understand the reason why the above sentence has two “is” simultaneously and the subordinate clause doesn’t have a verb. Is it a special structure? Please explain.

(2) “For guesses and doubts about the extent of his talents arouse more veneration than accurate knowledge of them, be they ever so great.”

I studied the “more ... than...” structure sometime ago, but I don’t know if a noun applied between the “more ... than” is correct. Please explain if inversion occurs in the subordinate clause.

(3) “No one must know the extent of a wise person’s abilities, lest he be disappointed.”

I don’t understand why the subordinate clause above uses the verb “be” after the noun “he.”

Thanks a million.

My reply to hairstyler:

(1)

I’m not surprised that you find the following sentence difficult to understand:

An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post.

It’s because it has an abstruse construction that makes it almost a fused or run-on sentence, and one that’s made more confusing by inadequate punctuation. This also explains why, as you pointed out, that sentence appears to be using the linking verb “is” simultaneously for no grammatically valid reason.

The first step to unraveling that sentence grammatically is to recognize that its first clause, “an ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness,” is meant to be some rule being quoted verbatim. As such, that whole clause should be set off by a pair of quotation marks to make it a grammatically legitimate part of that sentence, as follows:

“An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness” is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post.

We can see that when that quoted statement is set off by the pair of quotation marks, it becomes a noun form that serves as the subject of the main clause whose predicate is “the first and highest rule of all deeds and words.” In short, from a sentence structure standpoint, there’s actually only one linking verb “is” in that main clause—the one that links that quoted statement to the predicate of the main clause. Structurally, the other “is” doesn’t count because it’s integral to the quoted statement that’s functioning as the grammatical subject of that clause.

Now, these words that follow the first clause of that sentence in question may look like a subordinate clause but it really isn’t: “the more necessary to be followed the higher and more numerous your post. It’s actually a coordinate clause of the first clause, and together they form a compound sentence that normally would read as follows:

“An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness” is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, and the higher and more numerous your posts, the more it will be necessary to follow that rule.”

However, not only was the second coordinate clause inverted but it was also reduced or ellipted—some words were dropped from it, including the coordinating conjunction “and” and the linking verb form “to be”—to make the statement more concise and punchy, as follows:

“An ounce of wisdom is worth more than a ton of cleverness” is the first and highest rule of all deeds and words, [and] the more necessary [it has to be] to be followed the higher and more numerous your posts.”

(2)

Yes, a noun applied between the comparative “more ... than” is grammatically correct, as in the case of “veneration” in this sentence you presented:

For guesses and doubts about the extent of his talents arouse more veneration than accurate knowledge of them, be they ever so great.

The comparison being made is, of course, between two subjects, “veneration” and “accurate knowledge of (the extent of his talents).” But I don’t think inversion has been done to that sentence. What happened is simply that the adverbial modifier “be they ever so great” was moved to the tail end of the sentence for great impact. The normal position of that adverbial modifier is as follows:

For guesses and doubts about the extent of his talents, be they ever so great, arouse more veneration than accurate knowledge of them.

(3)

Regarding the use of the verb “be” after the noun “he” in the following sentence:

“No one must know the extent of a wise person's abilities, lest he be disappointed.”

The word “lest” is being used in that sentence as a subordinating conjunction that means “so as to prevent any possibility, and “lest” is a subordinating conjunction that requires that particular clause to be in the subjunctive mood, which in turn is a form that requires the linking verb “is” to always take the subjunctive form “be” regardless of whether the subject is singular or plural (“The proper use of the English subjunctive”).

Click to read comments or post a comment

“When is less more and when is more less?”

Question by Miss Mae, Forum member (August 15, 2011):

When is less more and when is more less in constructing sentences in English? When could writers just hope that their readers understand?

My reply to Miss Mae:

Sentences are just a tool of language; they need only as many words as needed to clearly and succinctly communicate an idea. Less than that is lacking, and more is superfluous; only when there’s prior and complete understanding between writer and reader can it be otherwise. At its core, writing is simply a sharing of mutually understood visual codes.

No, writers should never just hope that their readers will understand. They should always make an effort to be understood in as few words as possible. Using more words than needed often just engenders befuddlement rather than understanding.

Rejoinder of Miss Mae (August 16, 2011):

But when the subjects involved already knew what both of them are talking about, would it be okay to omit some words or phrases for brevity?

My reply to Miss Mae’s rejoinder:

It would be okay to omit some words or phrases for brevity, of course, but only when you are writing to an exclusive, one-on-one private audience—like your lover, sorority sister, or gang mate. In such situations, you can mutually develop and share codes as intimate, cryptic, or secretive as you want them to be. This will allow you to lop off entire phrases or clauses from your messages and still get yourself understood. But when writing for mass audiences like newspaper and magazine readers, you obviously can’t do that. You need to write full-bodied, grammatically and semantically correct sentences that can convey not only the basic information you want to share but also its various nuances. It will be dangerous to unilaterally drop words and phrases from your sentences on the assumption that your readers already know them beforehand. You will not only fail to communicate but also be perceived as a scatterbrain when you do that.

Click to read comments or post a comment

Which is correct: “Does absence (make, makes) heart grow fonder men?”

Question by Sky, Forum member (August 3, 2011):

Which one is correct?

1. “Does absence make heart grow fonder men?”

2. “Does absence makes heart grow fonder men?”

Response of melvinhate, Forum member (August 3, 2011):

“Does absence make man’s heart ponders?”

“Does absence make men’s hearts ponder?”

Sir Joe [probably] has better and detailed explanation. I also want to be corrected.

My response to Sky’s and melvinhate’s postings:

Both of Sky’s sentence constructions as well as both of melvinhate’s are grammatically wrong. Sky’s use of the comparative adjective “fonder” is correct, but the syntax of both of his sentences is faulty. On the other hand, melvinhate misuses the verb “ponder” in both of his sentences. The adjective “fonder,” of course, means “more indulgent or more affectionate” towards something—it’s the correct sense here--while the verb “ponder” means “to think about or reflect on,” which is semantically off the mark in that sentence.

The correct construction for that interrogative sentence is “Does absence make men’s hearts fonder?” This is actually the contemporary idiomatic expression “Absence makes men’s hearts fonder” in question form. That idiomatic expression is, in turn, an 18th century variation of a line from the poem “Elegies” by the Roman poet Sextus Propertius ((50–45 BC - circa 15 BC) that translates into English as follows:

“Always toward absent lovers love’s tide stronger flows.”

Rejoinder of Sky (August 6, 2011):

Why do we say “does absence make” and not “does absence makes”?

Rejoinder of melvinhate (August 6, 2011):

Thank you for the correction....

Thank you for sharing....

My response to Sky’s question:

In English, it’s the helping verb and not the main verb that takes the tense, and in sentences in the interrogative form, the helping verb takes the frontline position, as in “Does absence make men’s hearts fonder?” Here, the helping verb is “does”—the present tense form of the verb—and the main verb is “make”—the bare infinitive form of “to make” that has shed off the “to.” This is the prescribed form in English for interrogative or question-form sentences in the present tense. Of course, the helping verb here can also take the two other simple tenses—the past tense (“Did absence make those men’s hearts fonder?”), the future tense (“Will absence make those men’s hearts fonder?”)—and in every case, the main verb “make” remains in its bare infinitive form.

In the present perfect tense and past perfect tense, however, the helping verb and the main verb behave differently. The helping verb takes the perfect tense—“has,” “have,” or “had”—and the main verb takes the past participle form. That sentence you presented will then take the following forms—present perfect tense (“Has absence made those men’s hearts fonder?”) and past perfect tense (“Had absence made those men’s hearts fonder?”).

In the progressive tense, the main verb takes the progressive form and the helping verb takes the simple tense, as in the following examples—the past progressive tense (“Was absence making those men’s hearts fonder?”), the present progressive tense (“Is absence making those men’s hearts fonder?”), and the future progressive tense (“Will absence be making those men’s hearts fonder?”).

Click to read comments or post a comment

Should the conjunctions be always set off by commas?

Question by Miss Mae, Forum member (August 10, 2011):

I thought conjunctions should be set off by commas. Why is the sentence below from a news article in the BusinessMirror.com website an exception?

“A brief inquest hearing into Duggan’s death will take place tomorrow, though it will likely be several months before a full hearing is convened.”

My reply to Miss Mae:

No, it’s incorrect to think that conjunctions should, as a rule, be set off by commas. They require punctuation only on a case-to-case and situational basis, and some of them don’t need to be punctuated at all. You will recall that there are two kinds of conjunctions: the seven coordinating conjunctions (“for,” “as,” “nor,” “but,” “or,” “yet,” and “so”) and the subordinating conjunctions such as “because” and “even if” (there are actually at least 32 of them, so I won’t be enumerating them here). In addition to these two types of conjunctions, of course, there are also the conjunctive adverbs such as “however” and “nevertheless” (the most commonly used of them total 37), which provide stronger transitions than coordinating conjunctions and need to be punctuated differently.

It will take a very long discussion to describe the punctuation requirements of the various conjunctions and conjunctive adverbs, so I suggest that you refer to my book Give Your English the Winning Edge for more comprehensive instruction. Section 2, “Combining and Linking Our Ideas,” devotes four chapters on how the conjunctions and conjunctive adverbs work and on the proper way to punctuate them.

Now let’s take a close look at the conjunction used by the sentence you quoted from the Associated Press wire story that was carried by the Business Mirror:

“A brief inquest hearing into Duggan’s death will take place tomorrow, though it will likely be several months before a full hearing is convened.”

This sentence construction isn’t an exception to the rule at all. Here, the subordinating conjunction “though” is used in the sense of “even if,” marking the clause “it will likely be several months before a full hearing is convened” as subordinate to the main clause “a brief inquest hearing into Duggan’s death will take place tomorrow.” It correctly uses a comma at the end of the main clause, right before “though,” to set off the entire subordinate clause (including the subordinator “though”). This is done to provide a grammatical pause—a transition of sorts in the interest of clarity—between the main clause and the subordinate clause. Strictly speaking, though, that complex sentence can get by without that comma, but in the absence of that comma, there’s the clear danger of the reader missing that transition and getting confused in the process.

It’s also revealing and instructive how the subordinating conjunction “although”—a longer variant of “though”—can do a better, clearer job in such transition situations even in the absence of the comma:

“A brief inquest hearing into Duggan’s death will take place tomorrow although it will likely be several months before a full hearing is convened.”

(For greater clarity, though, I personally prefer using a comma before “although” even in such sentences.)

My point here is that in complex sentences, the decision to use or not to use the comma to set off the subordinate clause from the main clause will depend on the specific subordinating conjunction used, on the grammatical construction of the subordinate clause, and on the personal style of the writer.

Now let me go back to that idea of yours that “though” should be set off by commas. It actually happens in an altogether different grammatical situation where “though” is used not as a conjunction but as an adverb in the sense of “however” or “nevertheless,” as in the following sentence:

“For the sake of their children, though, she is valiantly putting up with her husband’s insensitivity to her needs.”

Now that’s a grammatical situation where using a pair of commas to set off “though” is truly warranted—but I must reiterate that this usage is adverbial rather conjunctive!

Click to read comments or post a comment

The positioning of modifying phrases isn’t just a matter of style

Questions e-mailed by Miss Mae, Forum member (July 27, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

I came upon this article this morning and wondered if the sentence construction was right.

“Qatar, buoyed by a successful bid to host the 2022 soccer World Cup, is interested in staging the start of the 2016 Tour de France.”

It was from the headline of a report expressing that country’s intention to host the 2016 Tour de France (“Qatar interested in hosting 2016 Tour de France start”). I am not a sports fanatic, but I would like to understand if the placement of modifiers/modifying phrases in a sentence is just a matter of style.

Also, in a grammatical query I asked you last February 6, you preferred the subject “I” to be stated after the phrase “in fact.”

My placement of “in fact”:

“I, in fact, am not sure till now of the proper usage of the auxiliary verbs ‘has,’ ‘have,’ and ‘had.’”

Your placement of “in fact”:

“In fact, I am not sure till now of the proper usage of the auxiliary verbs ‘has,’ ‘have,’ and ‘had.’”

I still do not understand why you did that and would really appreciate if you could address my confusion.

Respectfully,

Miss Mae

My reply to Miss Mae:

The placement of modifiers or modifying phrases in a sentence can be a matter of style, but the overriding consideration is the grammatical functionality of the placement. So long as the intended modification is clear and unmistakable, the writer can exercise some latitude in positioning the modifier or modifying phrase. The thing to avoid, though, is positioning a modifier or modifying phrase in such a way that makes it a misplaced modifier, a dangler, or a squinter (When footloose modifiers wreak havoc on news and feature stories).

Let’s take a close look at the sentence you presented:

“Qatar, buoyed by a successful bid to host the 2022 soccer World Cup, is interested in staging the start of the 2016 Tour de France.”

This positioning of the participial phrase “buoyed by a successful bid to host the 2022 soccer World Cup” is preferred by many newspapers and news service agencies. Its grammatical virtue is that it identifies the subject of the sentence right away for the reader. This is a big plus in day-to-day news journalism, where immediacy in the delivery and understanding of information is routinely given high priority.

In less hurried circumstances, though, particularly in the case of feature articles in weekly or monthly magazines, this other placement of that modifying phrase is likely or more often favored:

“Buoyed by a successful bid to host the 2022 soccer World Cup, Qatar is interested in staging the start of the 2016 Tour de France.”

This positioning of the modifying phrase gives the sentence what many editors call a “featurized” treatment or flavor. In fact, it’s often a good indicator of whether the story we are reading is a feature article instead of just straight news. We will also notice that when a feature article has a lead sentence written in this manner, the rest of the article will be told in sentences that often depart from the usual “subject + verb + predicate” construction expected from straight news—the better to deliver the featurized flavor of the story.

This positioning for the modifying phrase has a major drawback, though. It buries the subject—“delays” is perhaps a better word—so many words later in the sentence. In the sentence you presented, in particular, the frontline use of the phrase “buoyed by a successful bid to host the 2022 soccer World Cup” delays the delivery of the subject by as many as 12 words. This makes it longer and more difficult for nonnative speakers of English to understand what the sentence is all about, and the longer the modifying phrase is, the harder it will be for those readers to understand it. Of course, this shouldn’t be a problem for readers with a good grounding of how the English language works, but you see, mass-circulation newspapers and magazines always keep in mind the level of understanding of their average reader. They call this specific level of understanding the “readability index,” and I remember from my newspapering days so many years ago that the typical mass-circulation English-language newspaper tailors its news and feature stories to be understood by a 15-year-old, high-school level reader at the minimum.

Now, regarding your question about the positioning of the adverbial phrase “in fact” in the following sentences:

Here’s how you positioned “in fact”:

“I, in fact, am not sure till now of the proper usage of the auxiliary verbs ‘has,’ ‘have,’ and ‘had.’”

Here’s how I repositioned it:

“In fact, I am not sure till now of the proper usage of the auxiliary verbs ‘has,’ ‘have,’ and ‘had.’”

Both positions of “in fact” in the sentences above are grammatically acceptable, but the two sentences yield different meanings. By positioning “in fact” after the pronoun “I,” your sentence emphasizes the truthfulness of your being the person who’s not sure about the matter at hand. I don’t think this is the sense you intended for that sentence. Rather, you meant to affirm the truthfulness of your not being sure about the matter at hand, and this sense clearly comes through when “in fact” precedes the whole statement you want to affirm, as follows:“In fact, I am not sure till now of the proper usage of the auxiliary verbs ‘has,’ ‘have,’ and ‘had.’” In other words, “in fact” should modify that whole statement rather than just the first-person “I” that’s making the affirmation.

By the way, let me answer this question that you asked in an earlier e-mail: “What does ‘categorically deny’ mean?”

To “categorically deny” something is to deny it in an absolute and unqualified way. It’s to declare emphatically—often with a sense of outrage and righteousness—that an accusation is false and without any basis in fact.

Click to read comments or post a comment

Dealing with awkward sounding and wordy, overstated sentences

Question by jeanne, Forum member (July 7, 2011):

Hello Joe and everyone,

Is it just me or are these two sentences really awkward?

1. “We can ship to almost any address in the world.”

(*I feel like it should be “. . . any address around the world.”)

2. “We guarantee that we have, to the best of our abilities, determined the accuracy of the information presented in our listings. There is no money back guarantee for GAMSAT products.”

*Wouldn’t it be better to write instead, “We guarantee that we have determined, to the best of our abilities, that information presented in our listings are accurate”?

Since “our” here pertains to the shipping company (collective), shouldn’t “to the best of our abilities” be phrased as “to the best of our ability” instead?

I could be wrong, so I would really appreciate your comments.

My reply to jeanne:

I think the first sentence, “We can ship to almost any address in the world,” is grammatically airtight. I can hardly discern a difference between that sentence and your suggested version that uses “around” instead of “in,” We can ship to almost any address around the world.”

As to the second sentence, yours is a decidedly better construction. The original version doesn’t read very well because it ill-advisedly breaks the verb phrase “we have determined” with the adverbial phrase “to the best of our abilities.” Your version got rid of that break nicely. Both the original sentence and your improved version are wordy overstatements, though, and it hardly makes a difference whether “best of our abilities” or “best of our ability” is used.

I would simplify and make that sentence more concise, as follows:

“We guarantee the accuracy of the information presented in our listings.”

That’s 11 words vs. 20 words of the original, or a savings of 9 words (45%).

Click to read comments or post a comment

The case of the sentence whose subject is nowhere to be found

Question sent by e-mail by Neyo (July 1, 2011):

Hi, Joe!

I am an avid follower of your blog/forums and I find them very helpful in my job in a publishing.

My question is: Is the sentence below grammatically correct?

“Divided into quarters to correspond with the grading periods of school year, each quarter opens with pictorial summary (grades 1 – 3) and highlights (grades 4 – 6), which is a listing of what the pupils expect to learn in about two and a half months.”

I found it grammatically incorrect. Let us look at the part of the sentence that the modifier “divided into quarters to …” refers to. Obviously, it is the quarter (”each quarter”). If this is so, and if we remove the extension of the modifier, we read thus: “Divided into quarters…, each quarter opens….” This is an awkward construction, if not absurd for this purpose. (A quarter divided into quarters?) Now, using the same construction, and using “series” instead of “quarter” as a subject, we read thus: “Divided into quarters…, each series opens...”

Our chief editor, however, thinks otherwise. To him, there is no dangling modifier here. As he is a linguistics major, he even used the term exospheric referencing (ellipsed subject) used in linguistics, whatever that means.

Is this a situation of a dangling modifier or only an error in style? And is there an application of ellipsed subject here? (Note: “exophoric referencing” in the field of linguistics.) Is an ellipsed subject (if there is any) a rule in constructing a modifier?

Please help me convince my boss that there is an error in that sentence.

Thanks.

My reply to Neyo:

You asked if the following sentence is grammatically correct and whether it contains a dangling modifier:

““Divided into quarters to correspond with the grading periods of school year, each quarter opens with pictorial summary (grades 1 – 3) and highlights (grades 4 – 6), which is a listing of what the pupils expect to learn in about two and a half months.”

Offhand I’ll tell you that it’s a very badly constructed sentence, one with the following very serious grammatical flaws:

1. It has no subject either in the main clause or in the modifying participial phrase. Semantically, the noun “quarter” as used in the participial phrase and in the main clause itself can’t be the subject of that sentence. The sentence has therefore ended up saying so many things about nothing in particular. Indeed, unless some title or heading right before that sentence makes it clear what the subject is, I would consider that whole sentence itself as a meaningless statement.

2. That sentence having no subject, the modifying participial phrase up front has also ended up as a dangling modifier, unable to logically modify any noun in the main clause. As you said, because of the false use of the noun “quarter” as subject of that sentence, we have the grammatical anomaly of each “quarter” dividing itself up into “quarters,” a process that, when pursued to its logical conclusion, would yield a total of 16 divisions for whatever it is that the sentence is talking about.

3. Also semantically doomed as a dangling modifying phrase is the relative clause at the tail end of that sentence—“which is a listing of what the pupils expect to learn in about two and a half months.” This is because that relative clause doesn’t have a clear antecedent subject to modify in the main clause. The head noun of that relative clause, “listing,” has no clear syntactic relation to any of the nouns in the main clause, namely “quarter,” “pictorial summary,” and “highlights.”

4. The sentence also has three instances of missing articles (“the” twice, “a” once) and one instance of a missing modal (“can”), which to me are indicative of less than thorough copyediting.

You say that your chief editor considers that sentence grammatically correct. I think he is sorely mistaken and should reconsider his position. My feeling is that if someone has to defend a doubtful sentence construction by taking recourse to such abstruse linguistic terms as “exospheric referencing” and “ellipsed subject,” he must have painted himself into an indefensible position. The fact is that the sentence in question is meant to be read and interpreted not by linguistics majors but by elementary school teachers and pupils, so where’s the wisdom in writing it in a confusing way? And what’s the point in further confusing them with linguistic jargon and justifications that none of them will understand?

In fairness to your chief editor, though, I must say that you must have misheard him when you quoted him as using the term “exospheric referencing.” The word “exospheric” is a scientific term that means being located in “the outer fringe region of the atmosphere of the earth or a celestial body” (Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary). He must have said “exophoric reference,” a linguistics term used to describe generics or abstracts without ever identifying them, meaning that rather than introduce a specific concept, the writer refers to it by a generic word like “everything,” as in “Everything in my life is in shambles” for the opening of an essay. (Click this link for a layman’s discussion of “exophora” in the About.com website.) In any case, after looking very closely at the sentence in question, I simply can’t fathom precisely what word was used as “exophoric reference” in that sentence. And even if assuming that the “exophoric reference” was indeed clear in your chief editor’s mind, isn’t it foolhardy to expect nonlinguists to understand “exophoric reference” the way he has invoked it?

You say that your chief editor also used the alternative term “ellipsed subject.” By definition, an “ellipsis” is a grammatical device in sentence construction in which, after a certain word or phrase is mentioned in a sentence, that word or phrase is omitted when it has to be repeated later in the sentence. Ellipsis is meant to avoid needless repetition, to streamline sentences, and to make them easier to articulate, as in this ellipsed sentence: “Their older son is now a college graduate, the younger still in high school.” (The words “son” and “is” were ellipsed or omitted from this full sentence: “Their older son is now a college graduate, the younger son is still in high school.”) This being the case, I’m still wondering what subject or words your chief editor thinks were “ellipsed” from that sentence in question.

I realize that this critique of mine has gotten unduly long, so let me end it now by offering the following rewrite whose grammatical correctness won’t have to be defended by resorting to some linguistic mumbo-jumbo:

“Divided into quarters to correspond to the grading periods of the school year, each book in the series opens with a pictorial summary (for Grades 1 – 3) or highlights in text (for Grades 4 – 6) showing what the pupils can expect to learn in about two-and-a-half months.”

This time it’s unmistakable that the subject of the sentence are the books (or manuals or workbooks or pamphlets) in the series to be published, that the subject being modified by the participial phrase is “each book in the series,” and that “the pictorial summary” and “highlights in text” don’t really list but show “what the pupils can expect to learn in about two-and-a-half months.” It’s now in grammatically and semantically airtight English that I’m sure everybody will find easy to understand.

Click to read comments or post a comment

Some perplexing aspects of noun usage in English

Questions from English Maiden, new Forum member (June 15, 2011):

Hi, Joe!

I’m a new member of your Forum, and I’m hoping you can help me with my confusion about the English language.

Can you tell me what the differences, if any, between these sentences are:

A1. We are the masters of our own DESTINY.

A2. We are the masters of our own DESTINIES.

B1. People with diabetes can still have A NORMAL SEX LIFE.

B2. People with diabetes can still have NORMAL SEX LIVES.

Is there a difference in meaning between the sentences in each set? Or are the sentences completely the same? My confusion lies in what form of noun to use: the plural or the singular. I personally think that the plural forms of the nouns in sentences A1 and B1 are the correct ones to use. What do you think? I'll look forward to your answers.

My reply to English Maiden:

Welcome to the Forum, English Maiden!

First, let’s consider the word “destiny,” which could either be a countable noun or noncountable noun depending on its usage. It’s countable when it denotes what will happen to somebody in the future, particularly outcomes that he or she can’t change or avoid. On the other hand, it’s noncountable when it refers to the unknowable entity that’s believed to have the power to control events.

Now, in Sentences A1 and A2, “destiny” is obviously being used in the countable sense since it refers to the individual destinies of the people who comprise the plural pronoun “we.” Sentence A1, which pluralizes the count noun “destiny” into “destinies,” is therefore the correct sentence construction: “We are the masters of our own destinies.” Sentence A2, “We are the masters of our own destiny,” is grammatically and semantically wrong.

Let’s tackle the term “sex life” next. Obviously, the noun “life” is being used in the context of “human activities,” so it’s definitely a countable noun. This is in contrast to the use of “life” as a noncountable noun in the sense of the animating and shaping force in living things. The term “sex life,” then, is a countable noun that should be pluralized to “sex lives” when it refers to the individual sexual activities of the people who comprise the plural pronoun “we.”

Based on this grammatical analysis, Sentence B2 is the preferable sentence construction: “People with diabetes can still have normal sex lives.” I say preferable because Sentence B1 is also grammatically and semantically correct: “People with diabetes can still have a normal sex life.” Unlike the noun “destiny,” which is a countable noun that pertains solely to a particular individual, “sex life” can also be construed as a plural collective noun that pertains to people in general.

What this is telling us, English Maiden, is that whether a countable or noncountable noun will be plural or singular also depends on the nature and attributes of the noun itself and not just on its grammatical usage in the sentence.

Rejoinder from English Maiden (June 17, 2011):

Thanks for quickly responding to my post. I appreciate all your answers. I am still a tad confused, though. No, I’m still confused. I’ve encountered the following sentences, and I'm wondering if the singular nouns in them could also or should be in the plural:

1. Should women take their husband’s last name? (Would it also be correct to write “Should women take their husbands' last names?”?)

2. Good liars are often skilled at staring into their questioner’s eyes. (Wouldn’t it be better to change questioner’s eyes to questioners’ eyes to make it agree to the main subject of the sentence “good liars”?)

I don’t know if I’m just complicating things here, but I’m really confused. I hope you still respond. Thank you in advance!

My reply to English Maiden’s rejoinder (June 18, 2011):

No, you are not complicating things, English Maiden. You are dealing here with some truly perplexing aspects of English grammar that need explication from the standpoint of logic—not just of semantics—to be thoroughly understood.

In Item 1, both sentence constructions are not advisable. In modern monogamous societies, as we know, it’s highly unlikely for a woman to have more than one husband. The sentence “Should women take their husbands’ last names?” is therefore notionally untenable, so it’s more semantically appropriate to use the singular form for both the noun “women” and the noun “husband,” as in the following construction: “Should a woman take her husband’s last name?”

On the other hand, the sentence “Should women take their husband’s last name?” would be notionally possible in Muslim and other polygamous societies where a man could have one or several wives. In other words, a number of women can actually share the same husband. Asking the question “Should women take their husband’s last name?” therefore makes sense both grammatically and semantically. In monogamous societies, though, only the notionally singular sentence in Item 1 above would make sense semantically: “Should a woman take her husband’s last name?”

In the sentence constructions in Item 2, there’s no grammatical or logical need to make the operative subject, “good liars,” agree in number with the object of the preposition “into” (which in this case is either “their questioner’s eyes” or “their questioners’ eyes”). An object of the preposition is independent grammatically from the subject of a sentence, so it can take any number—whether singular or plural—irrespective of the number of the subject. We must keep in mind that the subject-verb agreement rule applies only to the relationship between a subject and its operative verb. This being the case, both versions of the sentence you presented are grammatically and semantically correct as general statements:

“Good liars are often skilled at staring into their questioner’s eyes.”

“Good liars are often skilled at staring into their questioners’ eyes.”

RELATED POSTING IN THE FORUM:

The Proper Use of “Amount” and “Number”

Click to read comments or post a comment

Which is correct: “endorsement of/endorsement from a medical society”?

Question by Jeanne, Forum member (June 23, 2011):

Hi everyone!

I would like to ask which of the following phrases is grammatically correct:

—endorsement of a medical society; or,

—endorsement from a medical society.

I thought that the first one is correct, but someone told me it should be the latter. I wonder what makes the difference.

Looking forward to your helpful responses.

My reply to Jeanne:

Both phrases are grammatically correct but they differ in usage and meaning. When “endorsement of a medical society” is used, it means that the medical society is the recipient of the endorsement from some entity, as in this sentence: “Endorsement of a medical society by the government is subject to prior review by its duly designated health agency.” On the other hand, when “endorsement from a medical society” is used, it means that the medical society is the giver or source of the endorsement to some entity, as in this sentence: “An endorsement from a medical society is needed to authorize a doctor to participate in the international health conference.” An equivalent phrase that yields this “giver” or “source” sense is “endorsement by a medical society,” as in this alternative sentence construction to the preceding example: “An endorsement by a medical society is needed to authorize a doctor to participate in the international health conference.”

Click to read comments or post a comment

A clarion call for simplicity in written communication

A friend, Charlie Agatep of the PR and advertising agency Agatep Associates in the Philippines, is sharing with Forum members the following e-mail he sent to the agency’s writers:

Dear All,

We’ve always said that Euro RSCG Agatep* is a university. We create a community of learning among our employees and our clients. We strive to do better tomorrow than we are doing today.

As part of our learning, I’d like to quote writer William Zinsser on the value of simplicity in written communication. He said:

“Clutter is the disease of... writing. We are a society strangling in unnecessary words, circular constructions, pompous frills and meaningless jargon.

“Our national tendency is to inflate and thereby sound important. The airline pilot who announces that he is presently anticipating experiencing considerable precipitation wouldn’t think of saying... ‘it may rain.’

“BUT THE SECRET OF GOOD WRITING IS TO STRIP EVERY SENTENCE TO ITS CLEANEST COMPONENTS. EVERY WORD THAT SERVES NO FUNCTION, EVERY LONG WORD THAT COULD BE A SHORT WORD, EVERY ADVERB THAT CARRIES THE SAME MEANING THAT’S ALREADY IN THE VERB, EVERY PASSIVE CONSTRUCTION THAT LEAVES THE READER UNSURE OF WHO IS DOING WHAT... THESE ARE THE THOUSAND AND ONE ADULTERANTS THAT WEAKEN THE STRENGTH OF A SENTENCE.

“Simplify, simplify. Thoreau said it, as we are so often reminded, and no American writer more consistently practiced what he preached. In his book, Walden, Thoreau said:

“‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’”

Zinsser continues:

“Writers must therefore constantly ask: what am I trying to say? Surprisingly they don’t know. Then they must look at what they have written and ask: have I said it? Is it clear to someone encountering the subject for the first time?

“Writing is hard work. A clear sentence is no accident. Very few sentences come out right the first time, or even the third time. Remember this in moments of despair. If you find that writing is hard, it is because it is hard.”

Thank you for your precious time.

Charlie A. Agatep

-------

*Euro RSCG Agatep PR (Agatep Associates Inc.) is an integrated marketing communications company specializing in strategic PR solutions for building, enhancing, and protecting corporate identity and brand reputation. It is part of the international PR network of the Paris-based Havas Group, a leading public communications company with operations in the USA, Europe, Middle East, and Asia Pacific.—Joe Carillo

Click to read comments or post a comment

The use of the expression “way back”

Feedback from Menie, Forum member (June 7, 2011):

I often see the phrase “Way back in 19xx...” and I cringe because I think the writer should have just said “In 19xx...” For me, a person who uses “way back” in this manner sounds verbose. And, for some reason, I always associate this term with people who were one generation older than me, those who grew up and were educated during the American time.

The following sentence from “Rotting fish due to fish-kills: another food for thought” By Dr. Flor Lacanilao is what set me thinking about this:

“Way back in 1961-1964, when there were no fishpens in the Lake, the annual catch of small fishers there was 80,000-82,000 tons.”

Does the use of “way back” here give any added value, or should the writer have said “From 1961 to 1964, when there were...”?

My reply to Menie:

The idiomatic expression “from way back” means “from far in the past” or “from a much earlier time.” It’s a rhetorical device to convey a long sweep of time between the present and some point in the past—a sense that may not come through as clearly if the writer or speaker simply used a particular date or numeric time frame. Figurative expressions like “from way back” certainly gives added value to exposition—I’d call it flavor—by counteracting the numerical blandness and tedium of matter-of-fact phrasing like “From 1961 to 1964…”

I don’t think it’s verbose to use “from way back” in exposition, but I agree with you that this expression does associate its users with people older than the reader or listener. Its users may not necessarily be people “who grew up and were educated during the American time”—any time frame for their growing up and education actually will apply to that usage—but by using that expression, they are often deliberately but subtly asserting their primacy over their reader or listener by virtue of their being older. That, to me, is a semantic bonus that goes with the use of “from way back” in personal narratives instead of just plain numeric chronology.

Click to read comments or post a comment

Do you need the IELTS to work or study in the US and Canada?

Question by zabi, new Forum member (June 2, 2011):

Is IELTS, the English exam, really needed for you to work or study in US, Canada, UK, Australia, and etc.? Or is there any other way? I am planning to learn English online, then to take IELTS exam if it is really needed by those countries.

My reply to zabi’s question:

IELTS, the acronym for the English Language Testing System, is an English-proficiency exam primarily designed for those who wish to work or study in the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth countries, including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. It’s the preferred exam for those destinations, but some of the British Commonwealth countries are now also using or about to use United States-based English proficiency tests. In particular, for student visa purposes, Australia now also uses the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) and will also be using the Pearson Test of English Academic (PTE Academic) later in 2011.

To be sure of the English-proficiency test you need to review for, check with the company or school in the foreign country of your choice.

Click to read comments or post a comment

Is it grammatically correct to use “will’s” in a sentence?

Question from Mark Kenneth Lopez, Forum member (May 22, 2011):

Sir,

Is it okay to use two “will’s” in one sentence?

Are the following sentences grammatically correct:

(1) “He will marry her before he will travel to Australia.”

(2) “He will marry her before he travels to Australia.”

My reply to Mark Kenneth:

The second sentence is correct:

“He will marry her before he travels to Australia.”

In complex sentences using “before” as subordinating time conjunction, it’s not grammatically correct to render two separate, independent, and nonsimultaneous future actions—one in the main clause and the other in the subordinate clause—both in the future tense. Doing so would make them appear to be simultaneous future actions (contrary to the premise that they are nonsimultaneous), as in the first grammatically flawed sentence you presented above:

“He will marry her before he will travel to Australia.”

When two clauses denoting future actions are linked by the subordinating conjunction “before,” those two actions obviously won’t be simultaneous, so the sentence must make it clear that one of the actions will occur earlier than the other. This sense is conveyed by making the earlier of the two actions take the future tense and the later action, the present tense. This was the case in the first sentence you provided, which is the grammatically correct construction:

“He will marry her before he travels to Australia.”

Conversely, when two clauses denoting future actions are linked by the subordinating conjunction “after,” the later action takes the future tense and the earlier action, the present tense, as in this sentence:

“He will travel to Australia after he marries her.”

These, as I said earlier, are the proper ways of using the tenses in complex sentences involving nonsimultaneous future events.

Click to read comments or post a comment

I’m sure you’ll love this hilarious but very instructive piece on language misuse. It was e-mailed to me by Forum member Rocky Avila last May 6, 2011. For readers who don’t understand Tagalog (the text set in italics), I have provided an English translation at the tail end of this posting. Enjoy!—Joe Carillo

Gobbledygook na Ingles at Tagalog

(“Inday ng Buhay Natin”)

Nawawala si Inday ngayon, kanyo? Nawawala nga. Ito, ikukuwento ko sa inyo, ang bahagi ng kanyang nagdaan sa bahay ng kanyang amo at may update din ako kung ano ang nangyari sa kanya:

Magsimula tayo noong mag-apply si Inday ng trabaho sa naging amo niya. Dumaan sa interview si Inday.

Amo: Kailangan namin ng katulong para maglinis ng bahay, magluto, maglaba, mamalantsa, mamalengke, at magbantay sa mga bata. Kaya mo ba ang lahat ng ito?

Inday: I believe that my acquired skills, training and expertise in management with the use of standard tools, and my discipline and experience will significantly contribute to the value of the work that you want done. My creativity, productivity, and work-efficiency and the high quality of outcome I can offer will boost the work progress.

[Nag-nosebleed ang amo pero tinanggap naman ng amo si Inday.]

Makaraan ang dalawang araw, umuwi ang amo, nakitang may bukol si Junior.

Amo: Inday, bakit may bukol si Junior?

Inday: Compromising safety with useless aesthetics, the not-so-well-engineered architectural design of our kitchen lavatory affected the boy’s cranium with a slight boil at the left temple near the auditory organ. Moreover, if you look more closely, he has rashes, too.

Amo: Ha?!!? Bakit?

Inday: Elementary, ma’am. Allergens triggered the immune response. Eosinophilic migration occurs in the reaction site & release of chemotactic & anaphylotoxin histamine & prostaglandins. This substance results in incomplete circulation to the site, promoting redness.

Amo: Ah, ganon ba? O, sige, ok. Sori, ha? [Sabay pahid ng kanyang dugo sa ilong]

Kinagabihan, habang naghahapunan…

Amo: Inday, bakit naman maalat ang ulam natin?

Inday: The consistency is fine. But you see, it seems that the increased amount of sodium chloride… the scientific name of which is NaCl…affected the taste drastically and the chemical reactions are irreversible. I do apologize.

[Nosebleed na naman ang ilong]

Amo: Bakit tuwing pag-uwi ko, nararatnan kitang nanunuod ng TV?!

Inday: Because I don’t want you to see me doing absolutely nothing.

[This time may kasabay pang himatay ang nosebleed.]

Isang gabi, may nag-text kay Inday—si Dodong, ang driver ng kapitbahay. Gustong makipagtext- mate. . .

Inday (to driver): To forestall further hopes of acquaintance, my unequivocal reply to your request is irrevocable denial.

Driver (to Inday): Inday, your perception has no substantial bearing on what the deep recesses of my being is contemplating. May I therefore assiduously move for your benevolent reconsideration. I was merely attempting to expand my network of interests by involving you in my daily experiences. Heretofore, however, if you so desire, you can expect an end to any verbal articulation from me!

Eh, narinig pala lahat-lahat ng amo ang pag-uusap nina Inday at ng driver.

Amo: Mula ngayon, walang magsasalita ng gobbledygook na Ingles sa pamamahay ko. Bakit di ka bumili ng libro ni Jose A. Carillo na English Plain and Simple? Reasonable price lang. Kung di mo kayang bumili dahil kuripot ka, hayaan mo’t ibibili kita. Ang sinumang magpadugo ng ilong ko at ng anak ko, palalayasin ko sa pamamahay na ito pagkatapos kong basagin ang bunganga!

Inday: Ang namutawi sa inyong bibig ay mataman kong ilalagak sa kasuluk-sulukan ng aking balintataw, sa kaibuturan ng aking puso, at palagi kong gugunam-gunamin. Sakbibi ng madlang lumbay kung mapapalis sa gunita yaring inyong tinuran.

Amo: Leche! Hindi kami sinauna! Ayaw ko ring makarinig ng gobbledygook na Tagalog! Yung makabagong wika at salita ang gusto kong gagamitin dito sa bahay ko!!

Inday: Tarush! Pachenes pa 'tong chorva eklavubo chuva tabayishki kun suplandish!

[Nasa ospital na raw ang amo. At hindi na ngayon mahagilap si Inday.]

---------

HERE’S AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THAT DIALOGUE:

“Inday of Our Life”

You say that Inday is missing? Indeed she is! So here, I’ll tell you the story of her past work in her lady employer’s household and I’ll also give you an update of what happened to her.

Let’s start when Inday applied for work with her employer. She had to go through a job interview.

Lady Employer: We need a househelp to keep the house clean, cook, do the laundry, iron clothes, do the groceries, and take care of the children. Can you do all that?

Inday: I believe that my acquired skills, training and expertise in management with the use of standard tools, and my discipline and experience will significantly contribute to the value of the work that you want done. My creativity, productivity, and work-efficiency and the high quality of outcome I can offer will boost the work progress.

[The employer had nosebleed listening to all that English gobbledygook, but she hired Inday nevertheless. (“Nosebleed” is slang for being assaulted with hard-to-understand language.) ]

After two days, the employer came home and found her son Junior with a big lump in the head.

Lady Employer: Inday, why does Junior have a big lump in the head?

Inday: Compromising safety with useless aesthetics, the not-so-well-engineered architectural design of our kitchen lavatory affected the boy’s cranium with a slight boil at the left temple near the auditory organ. Moreover, if you look more closely, he has rashes, too.

Lady Employer: What?!!? Why?

Inday: Elementary, ma’am. Allergens triggered the immune response. Eosinophilic migration occurs in the reaction site & release of chemotactic & anaphylotoxin histamine & prostaglandins. This substance results in incomplete circulation to the site, promoting redness.

Lady Employer: Oh, really? Well, OK. I’m sorry then. [She wipes the blood from her nose.]

That evening, at dinner…

Lady Employer: Inday, why is our food salty?

Inday: The consistency is fine. But you see, it seems that the increased amount of sodium chloride… the scientific name of which is NaCl…affected the taste drastically and the chemical reactions are irreversible. I do apologize.

[The lady employer gets nosebleed again.]

Lady employer: Why is it that whenever I come home, I always catch you watching TV?!

Inday: Because I don’t want you to see me doing absolutely nothing.

[This time the employer not only gets nosebleed but faints.]

One night, somebody sent Inday a text message—Dodong, the neighbor’s driver. He wanted to be Inday’s textmate…

Inday (to driver): To forestall further hopes of acquaintance, my unequivocal reply to your request is irrevocable denial.

Driver (to Inday): Inday, your perception has no substantial bearing on what the deep recesses of my being is contemplating. May I therefore assiduously move for your benevolent reconsideration. I was merely attempting to expand my network of interests by involving you in my daily experiences. Heretofore, however, if you so desire, you can expect an end to any verbal articulation from me!

[Well, it so happened that the lady employer heard every word of the conversation between Inday and the driver.]

Lady Employer: From now on, I won’t allow anybody to speak in gobbledygook in this household anymore. Why don’t you buy Jose Carillo’s book, English Plain and Simple? The price is reasonable. If you can’t afford it because you’re a cheapskate, let me buy you a copy. Whoever gives me and my children nosebleed again, I’ll smash her mouth and drive her out of this house!

Inday: (Roughly, her reply in Tagalog gobbledygook translates to English as follows): The words that issued from your lips I’ll keep in the deepest recesses of my mind, in the innermost sanctums of my my heart, and I’ll always ponder them ever so deeply. I’ll be very sad and it would be most unfortunate indeed if what you said gets erased from my memory.)

Lady Employer: Damn! We’re not old-timers here! I forbid you also to speak in Tagalog gobbledygook! What I want to hear in this house is modern-day language using modern-day words!!

Inday: Tarush! Pachenes pa 'tong chorva eklavubo chuva tabayishki kun suplandish!*

[The lady employer was hospitalized after this conversation. Inday is nowhere to be found.]

----------

*This is deep, demeaning gayspeak describing the lady employer as, among other insults, fat and haughty.

Click to read comments or post a comment

When three almost identical headlines say different things

Question sent in by e-mail by Ms. Ivy Mendoza (April 25, 2011):

Hello Mr. Carillo,

Which is correct among the three newspapers below with almost identical heads for their banner stories?

My reply to Ms. Ivy Mendoza:

Let’s take a closer look at those three news headlines in text form:

Manila Bulletin: Hopes dim for miners

Philippine Daily Inquirer: Hope dims for survivors

Philippine Star: Hopes dim for 17 miners

As headlines go, given the grammatical liberties usually taken by headline writers and the tolerance of readers for imprecise English in headlines, I think all three headlines do a fairly good job of capturing the essence of that news story in capsule form.

Grammatically and semantically, however, I think only the Manila Bulletin and Philippine Star versions would pass the litmus test. In these two headlines, “Hopes dim for miners” and “Hopes dim for 17 miners,” the word “dim” has the virtue of being interpreted either as an adjective in the sense of “faint” or as a verb in the sense of “to become faint.” When we think of “dim” as an adjective, the noun “hopes” can be taken as a subject (in the abstract sense of “expectations”) modified by “dim for miners” as an adjective phrase. In this sense, the act of “hoping” in that headline can be attributed to everybody who has a stake in the survival of the miners buried by the landslide: the miners themselves and their kin, the mining company, and the public at large. On the other hand, when we think of “dim” as a verb in that headline, the word “hopes” can be taken as a noun that does the intransitive action of “dimming.” In this alternative sense of that headline, the noun “hopes” can likewise be understood as the collective action of everybody who has a stake in the survival of the buried miners.

I would say, though, that the Philippine Star headline is more semantically precise than the Manila Bulletin’s because it qualified the reference of the headline only to the “17 miners” and not to all the miners who figured in that landslide. This semantic qualification is significant in that the miners who survived that landslide should, strictly speaking, no longer be counted among the objects of the hopes of being rescued.

Now, as to the Philippine Inquirer’s headline, “Hope dims for survivors,” it suffers from a semantic wrinkle because of its use of “dims” as a verb and of “hope” as the doer of the action of that verb. In that headline, the sense is not made clear as to who is doing the “hoping.” The apparent intent of that headline, though, seems to be that the “survivors” are the ones doing the “hoping,” but we can see right away that this is a wrong idea because the known “survivors” of that landslide are alive, already above ground, and no longer needs rescuing.

One cure I can see for this semantic wrinkle is to rewrite that Inquirer headline as follows: “Hope for survivors dims.” In this construction, the noun phrase “hope for survivors” clearly becomes the subject followed by “dim” as an intransitive verb. Here, it’s clear that what has dimmed is the expectation of saving more of the buried miners, and that it isn’t the “survivors” who are doing the “hoping” but everybody who has a stake in the survival of those buried miners.Click to read comments or post a comment

Identifying sentences by type and their direct and indirect objects

Question by Sky, Forum member (April 11, 2011):

1. “Could you give me some advice and tell me how to deal with the dilemma?”

2. “Some upperclassmen have warned us that no one can expect to get passing grades without efforts.”

3. “My excellent performances in high school kept me in the headmaster's honor list.”

What are the direct and indirect objects of the sentences above?

What is the usage of "that" in sentence 2?

How can we apply the S+V+O1+O2 (Subject+Verb+Object1+Object2)?

My reply to Sky:

Regarding your questions, Sky:

Sentence 1: “Could you give me some advice and tell me how to deal with the dilemma?”

This is a compound sentence with two coordinate clauses in the interrogative mood, linked by the coordinating conjunction “and”:

(a) Coordinate clause 1: “Could you give me some advice?”—subject: “you”; verb: “give”; indirect object: “me”; direct object: “some advice”

(b) Coordinate clause 2: “(Could you) tell me how to deal with the dilemma?”—subject: “you”; verb: “tell”; indirect object: “me”; direct object: the noun phrase “how to deal with the dilemma.”

Sentence 2: “Some upperclassmen have warned us that no one can expect to get passing grades without efforts.”

This is a complex sentence that consists of a main clause and a subordinate clause linked by the subordinating conjunction “that” :

(a) Main clause: “ Some upperclassmen have warned us”—subject: “upperclassmen”; verb: “have warned”; direct object: “us.”

(b) Subordinate clause: “that no one can expect to get passing grades without efforts”—subject: “no one”; verb: “expect” with modal “can”; direct object: the infinitive phrase “to get passing grades without efforts”

Sentence 3: “My excellent performances in high school kept me in the headmaster's honor list.”

This is a simple sentence consisting of the following:

(a) Subject: the noun phrase “my excellent performances in high school”

(b) Verb: “kept”

(c) Direct object: “me”

(d) Prepositional phrase: “in the headmaster's honor list” (functioning as an adverbial phrase modifying the verb “kept”)

Click to read comments or post a comment

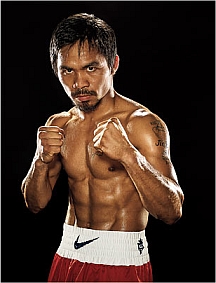

What do we do with Manny Pacquiao’s far from perfect English?

Manny Pacquiao is no doubt the world’s greatest and most accomplished boxer today, but some people don’t look kindly at the far-from-perfect English grammar they are seeing in his Twitter account.

In “Pacman blasts grammar critics,” a news story by Barry Viloria in abs-cbnNEWS.com datelined March 17, 2011, Pacquiao is reported to have retorted on Twitter: “Its doesn’t matter of the grammar as long they understand the message thanks.”

DEWEY NICKS FOR TIME MAGAZINE

The news story quotes Pacquiao as having continued his Tweet: “Tyong lhat pinoy ang slita ntin ay tgalog we should use our language we’re nt american, jpan,chna,atbp. They’re using there own language…We should proud in our language that’s the real pinoy yan ang tama thank you God Bless everyone.”1

It’s for this English that Pacquiao has been the target of some harsh criticism, among them this posting by someone who goes by the username tugakbatan: “It is the perception of a majority of Filipinos that ‘fluency’ in the English Language is the yardstick for education and/or intelligence. Kaya naman itong si Congressman Pakyaw ay English nang English kahit na mali-mali ang grammar. Pare ‘Tagalog’ na lang. Kagaya ni Lito Lapid. Bakit? Ano ba ang gusto mong palabasin? Alam naman namin na hindi masyadung malayo a narating mo sa pag-aaral. Pero sikat ka naman at sa buong mundo pa at naging congressman ka rin. Pare, I think there is nothing that you should prove more. Bibihira ang Filipinong maka-achieved nang ganyan. Kaya, mag-Tagalog ka nalang. No offense.”2

But Pacquiao and his English are definitely not lacking in defenders, among them someone with ther username 1STSACPCSAF who made this posting: “Leave Manny alone he’ll get better down the road Are’nt you guys proud we have a kababayan3 like Manny If you don't have any good things to say about Manny move to Africa and root for Monkeyweather.”

And this posting by jimsangco that’s summarily dismissive of the critics of Pacquiao’s English: “Wag mong intindihin un hayaan mo n lng sya...at hindi mo kelangan magpaliwanag at humingi ng pasensya...dahil pinoy k at tagalog ang language natin period.”4

------------

1This mix of Tagalog and English roughly translates into English as follows: “All of us Pinoys [Filipinos] speak Tagalog. We should use our language. We aren’t Americans, Japanese, Chinese, or others who use their own language…We should be proud of our language. That’s the real Pinoy, that’s the correct way. Thank you and God bless everyone.”

2The second to the last sentence of this passage roughly translates into English as follows: “But Congressman Pakyaw persists in speaking in English despite his faulty grammar. Chum, why not just speak in Tagalog. Like Lito Lapid [another congressman in the Philippines]. What are you trying to prove? After all, we know that you have not gone far in your formal education. Still, you are famous the world over and you have become a congressman besides. Chum, I think there is nothing that you should prove more. It’s so rare for a Filipino to have achieved that much. So please just speak in Tagalog. No offense.”

3The word kababayan is Tagalog for countryman.

4This Tagalog roughly translates into English as follows: “Don’t mind them and just let them be…and you don’t have to explain and say you’re sorry…because you are Pinoy and Tagalog is our language. Period.”

P.S. (March 23, 2011) The latest is that Manny Pacquiao has closed his Twitter account after a tiff with people who expressed dismay over his latest Tweets.

Read "Piqued Pacquiao throws in the towel on Twitter" in GMANewsOnline now!

Click to read comments or post a comment

The present progressive often denotes immediate future action

Question e-mailed by Miss Mae (March 13, 2011):

Dear Mr. Carillo,

Good day, Sir!

I just wondered. In your post replying to a question I sent by e-mail last week, “A Forum member’s comments on GMA 7’s ‘concised reporting’,” you changed “we are subscribing” to “we subscribe.” I thought the past progressive tense works just fine in that sentence.

Here is that part of my letter:

I tried to look for a copy of that commercial for your review but was not able to find one. Unfortunately too, we are subscribing to a different cable program to record one; I just happen to be in somebody else's house that day.

And here is the edited version:

I tried to look for a copy of that commercial for your review but was not able to find one. Unfortunately, too, we subscribe to a different cable program so I was not able to make a tape-recording of that TV ad. (I just happened to be in somebody else’s house that day when I saw that ad.)

Of course, I do not have any doubt that you were right. I just wish to understand what I thought I had done properly.

Respectfully,

Miss Mae

My reply to Miss Mae:

Dear Miss Mae,

In English, the present progressive form of an intransitive verb like “subscribe” very often conveys intent or a plan to do or undertake something in the immediate future. When we say “We are subscribing to The Manila Times,” for example, the sense is that of the future tense “We will subscribe to The Manila Times sometime soon” and not the continuing sense of the present tense “We subscribe to The Manila Times.” For this reason, if we receive the service of a cable-TV provider regularly on order, we don’t say “We are subscribing to a different cable-TV provider” (which means you intend to change your cable-TV provider with another one) but say “We subscribe to a different cable-TV provider” instead.

With my best wishes,

Joe Carillo

Click to read comments or post a comment

Is the question “Are you writing?” grammatically correct?

Question sent in by e-mail by Grace N. Toralde (February 20, 2011):

Dear Sir,

I would just like to ask something. Is the question “Are you writing?” correct?

If I ask someone “Are you writing also?”, am I using the correct tense?

My reply to Grace:

The question “Are you writing?” can be taken to mean in at least two ways.

The first is in the context of the speaker asking the person who is unseen or isn’t physically present—perhaps the question is asked over the phone or through a letter or e-mail—if he or she is currently doing some form of professional writing like, say, literature or journalism. The speaker knows that the person being addressed is a writer by profession or avocation and by asking that question, wants confirmation that the person being addressed is, in fact, pursuing that profession or avocation.

The second sense of “Are you writing?” is in the context of the speaker asking the person face to face if he or she is going to write the speaker sometime soon, in the same sense as that of the sentence “Will you write me soon?” or “Will you write me sometime soon?” In this particular case, the speaker is using the interrogative progressive tense form as the semantic equivalent of the interrogative future tense form—a usage that’s perfectly acceptable among native English speakers.

Both of the two senses above of the question “Are you writing?” likewise apply to the question “Are you writing also?” This time, however, the speaker is asking another person the same question he or she had earlier asked someone, and this someone happens to be within hearing distance when the question is asked the second time around. The adverb “also” is added by the speaker to convey the idea that the person he had earlier asked that question answered in the affirmative.

In all the situations described above, the questions “Are you writing?” and “Are you writing also?” are grammatically correct and in the right tense.

Click to read comments or post a comment

What’s the correct usage for the verbs “brought” and “taken”?

Question from Isabel Escoda in Hong Kong (February 13, 2011):

Hey Joe—I hope you can help me out regarding a verb that’s been bothering me for a long time, one which I believe is always used in the wrong way by Pinoy journalists. It’s the past tense of the verb “bring”—“brought.”

Today a friend in Manila forwarded an article about Gen. Angelo Reyes who committed suicide. The story had that pesky word in this sentence: “His body will be BROUGHT to Camp Aguinaldo…”

Shouldn’t the verb be TAKEN since the reporter is writing about something that isn’t being delivered to HIM (the reporter) but to somewhere else? In other words, someone BRINGS something to me, while one TAKES something to a point away from me. Am I explaining this clearly?

Other journalistic examples: “He was BROUGHT to the police station” is always used (when it should be TAKEN); “She was BROUGHT to the hospital”—again, that should be TAKEN. One is dealing with coming and going—so why do folks get this wrong so often?

Cheers,

Isabel

My reply to Isabel:

The verbs “bring” and “take” are actually synonymous in the sense of “to convey, lead, carry, or cause to go or come along to another place,” but the choice between the two depends on the point of view or position of the speaker in relation to the action described. When the movement is clearly toward the place from which the action is being regarded or where the speaker is, was, or will be, “bring” is conventionally used, as in “Bring your friend here” and “Your mother brought me a slice of carrot cake yesterday.” On the other hand, when the movement is clearly away from which the action is being regarded or where the speaker is, was, or will be, “take” is conventionally used, as in “Take your friend to the zoo” and “Your sister took some gardenias from my garden this morning.”

In the case of most news stories, however, the speaker is usually an absent third-person narrator objectively describing the action; as such, he or she is an observer who makes it a point not to get involved or doesn’t intrude into the action. In short, in news told objectively, the news reporter is neither here nor there, and this is when the usual distinctions between “bring” and “take” no longer apply. Such is the case of the news reporter who, as you quoted from that article about Gen. Angelo Reyes’s suicide, wrote “His body will be brought to Camp Aguinaldo…” Now, you ask if “brought” is incorrectly used here and if “taken” should be used instead. I think that from the news reporter’s point of view as an absent spectator, “brought” and “taken” are both correct and can be used interchangeably.

For the same reason, the two other journalistic examples you presented, “He was BROUGHT to the police station” and “She was BROUGHT to the hospital,” are also grammatically airtight, but, of course, so are these versions that use “taken” instead of “brought”: “He was TAKEN to the police station” and “She was TAKEN to the hospital.” From the standpoint of the objective reporter, the “brought” versions and the “taken” versions aren’t dealing with coming and going. Indeed, they are not dealing with actions towards or away from the speaker, but with lateral actions in front of his eyes, as if on a stage tableau. In such situations, as I said earlier, the distinctions between “bring” and “take” don’t apply.

Click to read comments or post a comment

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to post)