- HOME

- INTRO TO THE FORUM

- USE AND MISUSE

- BADLY WRITTEN, BADLY SPOKEN

- GETTING

TO KNOW ENGLISH - PREPARING FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TESTS

- GOING DEEPER INTO ENGLISH

- YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

- ADVOCACIES

- EDUCATION AND TEACHING FORUM

- ADVICE AND DISSENT

- MY MEDIA ENGLISH WATCH

- STUDENTS' SOUNDING BOARD

- LANGUAGE HUMOR AT ITS FINEST

- THE LOUNGE

- NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

- ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

- Long Noun Forms Make Sentences Exasperatingly Difficult To Grasp

- Good Conversationalists Phrase Their Tag Questions With Finesse

- The Pronoun “None” Can Mean Either “Not One” Or “Not Any”

- A Rather Curious State Of Affairs In The Grammar Of “Do”-Questions

- Why I Consistently Use The Serial Comma

- Misuse Of “Lie” And “Lay” Punctures Many Writers’ Command Of English

- ABOUT JOSE CARILLO

- READINGS ABOUT LANGUAGE

- TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

- NEWS AND COMMENTARY

- BOOKSHOP

- ARCHIVES

Click here to recommend us!

ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

On this webpage, Jose A. Carillo shares with English users, learners, and teachers a representative selection of his essays on the English language, particularly on its uses and misuses. One essay will be featured every week, and previously featured essays will be archived in the forum.

A cautionary tale of a man’s unyielding aversion to change

One of the earliest narrative essays that I wrote for my English-usage column in The Manila Times is “A World Without English,” a cautionary tale about a man in our old farming neighborhood who neither believed in educating his children nor in learning English as a second language. It first appeared in my column in the latter part of 2002—the year when the column started—and subsequently became part of my 2004 book, English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. I think it will be timely reading for the opening of the Philippine schoolyear next month so I decided to post it in this week’s edition of the Forum. (May 25, 2014)

Click on the title below to read the essay.

In the farming village where I grew up there was a man—a maker of homemade coconut oil—who did not believe in anything his mind could not grasp or which lay outside the life he knew. Let us call him Pedro de la Cruz. He was born at about the same time as my father in the early decades of the last century, but for some reason his schooling was cut short in the second grade, while my father went on to normal school in Manila to become a schoolteacher. Pedro thus could not understand, write, or speak English beyond the usual peremptory greetings like “Good morning!” or “Good afternoon!” Even these he affected to be beneath his dignity saying. In fact, he viewed with contempt people who spoke English in his presence; once they had left, he would spit on the ground and call them social climbers who surely would not make it to wherever it was they were going. “Mark my words,” he would say in the dialect, “they who think they are so good in a foreign tongue will soon come crashing to the ground!”

Pedro, along with his whole family, was intensely religious. Prayer colored his day as it did his wife Pilar’s, who was also hardly literate; his eldest son Gregorio, who was my classmate in grade school; Jacinto, the next born; and Teresita, their only daughter. Every morning when the parish church bell rang some two kilometers away, and again at Angelus, they would stop their hand-driven coconut press and pray all the Mysteries of the Holy Rosary. Sundays they would don their Sunday’s best for Holy Mass without fail, all five going to church on foot. Their religiosity, together with the almost unceasing oil-making in their small, hand-driven mill, was the central unifying force of their lives.

Pedro was fiercely obstinate about the worldview that sustained this way of life. One time, back from Manila during a summer college break, I made the mistake of discussing Darwin’s Theory of Evolution with him. I explained that Darwin had determined that man might have sprung from the same prehistoric ancestral stock as that of the apes. This launched Pedro into a strangely eloquent diatribe against the false beliefs fostered by science and the infidels they produced. He gave me the disconcerting feeling that I was the biology teacher being prosecuted by William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes Monkey Trial, the only difference being that Clarence Darrow was nowhere around to defend me. And on matters like this, Pedro simply had to have the last word. You had to give up the argument because if you didn’t, it would go on past midnight in his hut, which in those days without electricity would be lit only by a flickering coconut-oil lamp.

Pedro’s deep religiosity resulted in a frightening determinism. “Not a leaf will fall from the tree if God will not will it,” he would intone with fire in his eyes, “and that leaf will surely rise back to the twig if he wished it.” He also believed that God would surely provide for his family no matter what happened. For this reason, he did not think it necessary for any of his children to be educated beyond the level he had attained. In fact, he thought that every learning beyond this was simply a form of needless expense, a totally irrelevant enterprise that would only corrupt the way one ought to earn a living, grow into adulthood, raise a family, and end up in the grave like everybody else.

The impact of this worldview was most profound in the case of Gregorio, who was in the same class with me from the second to the sixth grade. Gregorio’s talent in arithmetic was astonishing. He could add an eight-level array of ten-digit numbers in less than a minute, and could multiply a ten-digit number by another ten-digit number almost as fast. His grasp of English, unfortunately, was just above rudimentary. There had been no English-language reading materials in the de la Cruz household to stoke the fires of his otherwise brilliant mind, and the siblings could not or did not dare speak English with him. There was also no radio to stimulate his English comprehension; his father thought it a nuisance and a vexation to the spirit (TV was still a good 25 years away into the future). Had his English been at least as good as mine, which was by no means that good, I have no doubt that he would have been our class valedictorian. He could have gone on to high school and college and surely could have made something of himself, perhaps a mathematics or physics professor in a major university. But this was not be.

Because Pedro did not send anyone of the siblings to high school and kept a life of penury, no money went out of the family bourse except those that went to food and the upkeep of their manual oil-making equipment. He kept his hut the thatched roof affair that it had always been, dismissing galvanized iron sheets as no good because they got so hot in summers; bought no motor vehicle, preferring to move on foot as always and to continue using a carabao-drawn cart to haul coconut and other cargo to his oil mill; and forced his family to live totally without entertainment and vice. This made the de la Cruz family outwardly prosperous and even enabled them to extend loans to the neighborhood in the form of coconut oil or petty cash. An emboldened Pedro could thus boast to the villagers that without even learning a word of English and without making his children take nonsense subjects in high school and college, his family was better off than most except the jueteng operator and the U.S. Navy pensionados in town.

The neighborhood grew and flowed out; villagers moved to town, to the cities, to countries unknown and unheard off; houses big and small, built by money from overseas, sprouted all over. But Pedro’s hut stood unruffled and unchanged. After he and his wife passed away, the de la Cruz siblings continued to live in the same small, unfenced plot of land. They built satellite huts around their father’s, raised families, and set up their own hand-driven oil mills. But each had no dream or ambition beyond what their father had decreed. From each of the four hand-driven mills there would issue, day in and day out, the same peculiar sweetish odor of burnt coconut. Pedro’s legacy of a world without English would keep it that way until it had totally spent itself.

---------------

This essay originally appeared in the author’s “English Plain and Simple” column in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently became part of his book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language © 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright 2008 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

Previously Featured Essay:

It is a very private story that I occasionally tell, but only to aspiring literary types, younger executives, and teenage bookworms who find time to ask me what is a good English-language book or novel to read. The story is about how, many years ago, I discovered Gabriel García Márquez in the romance section of a big bookstore at Claro M. Recto Avenue in Manila. It was shortly before or right after martial law had taken the life of the daily paper where I worked as a roving reporter, I cannot remember the exact date now. But there was Marquez, still a total stranger to me, in the Avon hardback edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien Años de Soledad in the original Spanish), enjoying in the same shelf the company of such rupture-and-heartbreak novelists as Emily Loring, Barbara Cartland, and Jacqueline Susann. No, García Márquez did not get there as an occasional stray, chucked absentmindedly or insensitively into the shelf by some browser. If memory serves me well, the book had been actually misclassified and miscatalogued in the same genre as the more popular company it was keeping when I found it.

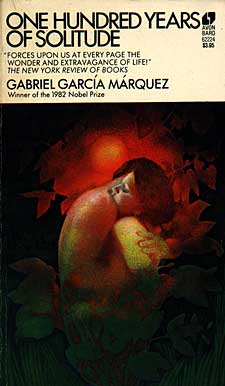

The reason why it got there was probably serendipity of the most sublime order, but I think you can dismiss that thought as just me imagining the whole thing in chronological reverse. A more plausible reason was that it had the green and grainy cover art of a naked man and woman in passionate embrace, which I later thought was the publisher’s well-intentioned attempt to make the Buendia family’s otherwise unimaginable tragedies and grief more commercially acceptable. It was actually this somber study in solarized chiaroscuro that drew my eye to the book. When I began to leaf through it, however, furtively expecting some passages about women in the throes of illicit sex, I read something much more exciting, much more stimulating, and much more intriguing. “Many years later,” García Márquez began, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” A few passages later I was irretrievably sold to the book. I promptly paid for it, tearing the plastic wrapping no sooner had the sales clerk sealed it, and started to read as I trudged the sidewalk on my way to my apartment somewhere in the city.

When I had read the book twice or thrice and still couldn’t get over the thrill of the discovery, I excitedly recommended and lent it to a broadcast acquaintance at the old National Press Club. I can’t remember now who the borrower was, but he was one of those press club habitues who would dawdle over beer or gin tonic at the bar till somebody’s self-imposed midnight closing song-and-piano piece was over. What I do remember is that he never returned it to me. He assured me, however, that he had read it and enjoyed it so much that he could not resist lending it to someone—was it Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil or the late Renato Constantino?—who in turn lent it to someone who lent it to someone until finally the chain in the lending was lost. The last I heard from the original borrower was that the book had been passed on to an English Lit. professor at the University of the Philippines, where a few years later I was to learn that it had become mandatory reading in its English graduate school.

Being pathetically inept in Spanish I could never really know what Castilian or Colombian idioms I missed in the English translation, but the English-language García Márquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude truly set my mind on fire. He lit in me a tiny flame at first, then a silent fire for language that burned even brighter with the passing of the years. He was not only robust and masterful in his prose but devastatingly penetrating in his insights about the flow and ebb of life in the archetypal South American town of Macondo. Not since I chanced upon a battered copy of The Leopard (Il Gatopardo in the original Italian) by the Italian writer Giuseppe di Lampedusa two years earlier, this time a real stray in a smaller bookstore nearby, had I seen such soaring yet quietly majestic writing. Here is García Márquez at his surreal best: “Fernanda felt a delicate wind of light pull the sheets out of her hands and open them up wide. Amaranta felt a mysterious trembling in the lace on her petticoats as she tried to grasp the sheet so that she would not fall down at the instant when Remedios the Beauty began to rise. Ursula, almost blind at the time, was the only person who was sufficiently calm to identity the nature of that determined wind and she left the sheets to the mercy of the light as she watched Remedios the Beauty waving goodbye in the midst of the sheets of the flapping sheets that rose up with her…” With prose like this I became a García Márquez pilgrim, re-reading One Hundred Years of Solitude countless times and devouring, like an adolescent glutton, practically all of his novels and short-story collections in the years that followed.

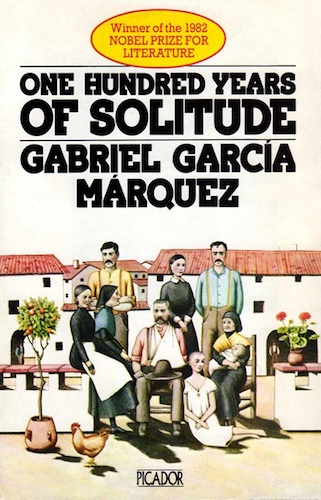

Many years later, in 1982, I was to discover in the morning papers that García Márquez had so deservedly won the Nobel Prize for literature. I was so happy for the new Nobel Laureate and for myself, and I no longer thought anymore of ever recovering that first copy of him that I had the pleasure of retrieving from the company where it obviously didn’t belong. In homage I went back to the bookstore where I first found García Márquez, quietly and almost reverently picking up a new Picador paperback edition of him. Its cover art was no longer the man and woman in the deathless embrace, but this time an image more faithful to the elemental truth of the book: the whole Buendia family in a portrait of domestic but elegiac simplicity, at one and at peace with the chickens and shrubs and flowers that gave them sustenance, awaiting the last of the one hundred years allotted to them on earth.

The book is mottled with age and yellow with paper acid now. Now and then I would lend it to a soul that is intrigued why I would keep such a forlorn book on my office desk, but only after tragicomically extracting an elaborate pledge that he or she would really read it and give it back to me no matter how long it took to finish it.

--------------

This essay originally appeared in the author’s “English Plain and Simple” column in The Manila Times in 2002 and subsequently became Chapter 40, Section 7 of his book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language. Copyright 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright 2008 by Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.

Click to read more essays (requires registration to post)