- HOME

- INTRO TO THE FORUM

- USE AND MISUSE

- BADLY WRITTEN, BADLY SPOKEN

- GETTING

TO KNOW ENGLISH - PREPARING FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TESTS

- GOING DEEPER INTO ENGLISH

- YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

- ADVOCACIES

- EDUCATION AND TEACHING FORUM

- ADVICE AND DISSENT

- MY MEDIA ENGLISH WATCH

- STUDENTS' SOUNDING BOARD

- LANGUAGE HUMOR AT ITS FINEST

- THE LOUNGE

- NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

- ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

- Long Noun Forms Make Sentences Exasperatingly Difficult To Grasp

- Good Conversationalists Phrase Their Tag Questions With Finesse

- The Pronoun “None” Can Mean Either “Not One” Or “Not Any”

- A Rather Curious State Of Affairs In The Grammar Of “Do”-Questions

- Why I Consistently Use The Serial Comma

- Misuse Of “Lie” And “Lay” Punctures Many Writers’ Command Of English

- ABOUT JOSE CARILLO

- READINGS ABOUT LANGUAGE

- TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

- NEWS AND COMMENTARY

- BOOKSHOP

- ARCHIVES

Click here to recommend us!

STUDENTS’ SOUNDING BOARD

We’ll be glad to help clarify matters about English usage for you

This Students’ Sounding Board is a section created especially for college and high school students. On request, it will provide informal advice and entertain discussions on specific questions, concerns, doubts, and problems about English grammar and usage as taught or taken up in class. If a particular rule or aspect of English confuses you or remains fuzzy to you, the Students’ Sounding Board can help clarify it. Please keep in mind, though, that this section isn’t meant to be an editing facility, research resource, or clearing house for student essays, class reports, term papers, or dissertations. Submissions shouldn’t be longer than 100-150 words.

To post a question in the Students’ Sounding Board, the student must be a registered member of Jose Carillo’s English Forum. To register, simply click this link to the Forum’s registration page; membership is absolutely free. All you need to provide is your user name along with a password; you can choose to remain incognito and your e-mail address won’t be indicated in your postings.

Why is Steven Pinker popular in language and psychology?

Question by justine aragones, Forum member (March 28, 2014):

What do you think are the reasons why Prof. Steven Pinker is popular in the fields of language and psychology? Has he contributed some breakthrough in the study of language?

My reply to justine aragones:

I think Steven Pinker is immensely popular in the fields of language and psychology primarily because he has the talent to come up with bold and provocative ideas in those disciplines, coupled with the ability to explain those ideas not just in abstruse academic and scientific jargon but in highly accessible layman’s English as well. He is also an immensely prolific writer who, before age 60 (he hits 60 on September 18, 2014), has already chalked up a total of six general-audience books that have become bestsellers: The Language Instinct (1994), How the Mind Works (1997), Words and Rules (2000), The Blank Slate (2002), The Stuff of Thought (2007), and The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011). This is on top of several academic books and scores of articles and essays on his wide-ranging thoughts and research as a linguist and psychologist.

What may be considered as a breakthrough that Pinker has contributed to linguistics is his general theory of language acquisition that he applied to how children learn verbs. His theory, which built on the groundbreaking linguistic ideas of noted American linguist Noam Chomsky, postulated that certain simple language errors committed by young children capture the essence of language itself. Pinker observes that when a three-year-old says “I eated the ice cream” or “We holded the kittens,” he or she follows a grammar rule correctly but makes a mistake only because adult speakers happen to suspend the rule for those verbs in English. This, Pinker theorizes, points to the presence of innate cognitive machinery—a “language instinct”—that enables a young child to construct novel linguistic forms by following rules.

I would think though that this language-instinct theory is but a small fraction of Pinker’s many contributions to the science of linguistics and psychology. For a better and deeper appreciation of the body of his works and the dizzying range of his fields of interest, I suggest you read Oliver Burkeman’s interview story of him in CNN.com, “Steven Pinker: ‘We don’t throw virgins into volcanoes any more’.” That quote alone from Pinker should give you an idea of how provocative and controversial he could be in espousing his pet theories—a factor that’s obviously another major engine that drives his immense popularity.

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

Legalese causes sudden language disconnect in job application

Question by justine aragones, Forum member (February 20, 2014):

I do not know if this is the right forum to ask this question but I hope you will share your insight for this one: Is it necessary to put the declaration below at the tail end of a resume?

“I hereby certify that the above information is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief.”

My reply to justine aragones:

The language of that statement smacks of legalese, and no level-minded job-seeker really would speak or write that way, but it serves the purpose of making the job application a sworn statement. That, of course, warms the cockles of legal-minded recruiters and personnel officers, who need some form of assurance that the applicant at least isn’t making blatant lies in his or her curriculum vitae.

POSTSCRIPT:

Lest it be misconstrued that I’m being facetious, I’d like to add a postscript as to how that statement, shorn of legalese, might sound like an authentic educated job-seeker speaking in plain and simple English: “I affirm that this résumé is true and correct.”

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

Precisely what grammar aspect governs subject-verb agreement?

Question by justine aragones, Forum member (February 4, 2014):

May I know the rule in subject-verb agreement that governs in the question “Are you a member of Church of Christ, who (is, are) a student of Bulacan State University?”

My reply to justine aragones:

To be able to answer your question, let me first refine the grammar and syntax of that sentence you presented. It should be reworded as follows to be analyzed properly: “Are you the member of the Church of Christ who (is, are) a student of Bulacan State University?”

With the question reworded that way, it will achieve subject-verb agreement by using the singular “is” instead of “are”: “Are you the member of the Church of Christ who is a student of Bulacan State University?”

That sentence has for its subject complement the entire noun phrase “the member of the Church of Christ who is a student of Bulacan State University.” In English grammar, a noun phrase is categorized as a nominal group, which by definition consists of a head noun and all the other words that modify or characterize that noun. The words that precede the head noun are called its premodifiers, and the items that come after it are its qualifiers. In the noun phrase “the member of the Church of Christ who is a student of Bulacan State University,” the head noun is logically the word “member,” the word “the” that precedes it is its premodifier, and the words “of the Church of Christ who is a student of Bulacan State University” that come after it are its qualifiers.

Grammatically, it is the head noun that determines whether the noun phrase is singular or plural. Indeed, in a noun phrase, the form of the operative verb is always determined by the number of the head noun—the verb takes the singular form when the head noun is singular and takes the plural when the head noun is plural. Any other noun or pronoun found in the premodifier or in the qualifier of the head noun doesn’t determine or affect its being singular or plural.

In the noun phrase “the member of the Church of Christ who is a student of Bulacan State University,” the head noun “member” is singular, so it requires the singular form “is” of the verb “be” rather than its plural form “are.” (The pronoun “you,” which requires the plural form “are” of the verb, shouldn’t be mistaken for the head noun here because it isn’t really part of that noun phrase.) This, in sum, is why the singular “is” is the correct form of the operative verb in the question “Are you a member of Church of Christ who is a student of Bulacan State University?”

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

Is the use of the expression “huge amount of work” correct?

Question by justine aragones, Forum member (January 14, 2014):

Is the phrase “a huge amount of work” grammatically correct?

My reply to justine aragones:

Yes, “a huge amount of work” is grammatically correct and perfectly acceptable phraseology. As a general measure of quantity, “amount” is practically synonymous with “volume” for indicating the total of a thing or things in number, size, value, or extent. Indeed, the sense of “a huge amount of work” is in general almost indistinguishable from that of “a huge volume of work”

However, when it comes to describing specific kinds of work, there’s a difference in nuance between “amount” and “volume.” In particular, lots of work of an abstract nature such as reading, thinking, or surveillance is more precisely described as “a large amount of work,” while lots of measurable physical work like loading a pile of boulders into a truck is more precisely described as “a large volume of work.” Some dissonance might be perceived if lots of abstract work is described as “a large volume of work” instead, but no such dissonance will be perceived if lots of physical work is described as “a large amount of work” instead. The differences will be largely subjective, with different writers or speakers gravitating to either “amount” or “volume” as a matter of temperament or personal style. Either way, it will be needless or foolhardy to fault them for their choice of usage.

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

Should we call the song band “Carpenters” or “The Carpenters”?

Question by justine aragones, Forum member (January 20, 2014):

I love the songs of Karen and Richard Carpenters but I am so finicky when it comes to the band’s name. What do you think is the right way to call them: “Carpenters” or “The Carpenters”? Now I just follow the “Carpenters,” which is the name they signed under A&M records in 1969.

My reply to justine aragones:

Calling them “The Carpenters”—with the capitalized definite article “The”—is the appropriate and grammatically correct way, in much the same way that place name “The Netherlands” formally requires the capitalized “The.” The presumption in the use of such capitalized appellations as “The Carpenters” is that the performers for which the name stands have the same family names (or, if they have different surnames, belong to the same family), and have decided to use the appellation as a brand or trademark. In the case of such place names as “The Netherlands,” the use of the capitalized definite article “The” and the proper name in plural is meant to indicate a collection of islands, mountains, or other geographic features. The capitalization of the “The” is a just matter of choice and style, though; in the case of “the Philippines,” for instance, the official style doesn’t require capitalizing the “the.”

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

Putting an end to the annoying “at the end of the day” plague

Question by justine aragones, Forum member, December 30, 2013:

I wonder why most college debaters always use the phrase “at the end of the day.” Is there any way to minimize such use or totally avoid it?

My reply to Justine:

It’s really no surprise that many college debaters, even the finest of those who joust in the long-running TV debate competitions on ANC, use “at the end of the day” much, much too often for comfort. They have the misguided notion that very liberally spicing their talk with that figurative expression for “ultimately,” “in the end,” or “after all” is a sign of wisdom, discernment, and sophistication. Being young and mostly impressionable, they have become unwitting copycats of the wrong adult role models for spoken English.

Indeed, the high incidence of “at the end of the day” in college debates is abetted by the fact that even the highest official of the land, perhaps one out of four legislators and public officials, and probably the same ratio of TV talk-show hosts, news anchors, and guests use “at the end of the day” with such annoying frequency. They are embarrassingly unaware that this expression has been repeatedly condemned over the years as the most irritating cliché in the English language.

Way back in 2004, in a survey conducted in 70 countries by the London-based Plain English Campaign, “at the end of the day” ranked first among the most hated English clichés worldwide. The group’s spokesman commented about that finding: “Using these terms in daily business is about as professional as wearing a novelty tie or having a wacky ring-tone on your phone. When readers or listeners come across these tired expressions, they start tuning out and completely miss the message—assuming there is one.”

Again, in 2005, in a poll of 150 senior executives in corporate America by the temporary staffing company Accountemps, “at the end of the day” ranked first among the 15 most annoying clichés. And in 2006, in a poll of 10,000 news sources that included 1,600 American newspapers, the Australian-based database company Factiva found “at the end of the day” at the top of the 55 most overused English clichés.

In truth, adverbial phrases like “at the end of the day” are not meant to call attention to themselves but just to flag an important point to be made by the speaker. As such, they must be used sparingly to avoid irritating the listener or reader. For many college debaters and public speakers, however, such phrases have become a pernicious semantic crutch, creating such a strong dependency that the speakers encounter serious difficulty speaking their minds without it.

But yes, now that you ask, there’s definitely a way to minimize the use of “at the end of the day” or totally avoid it.

First, high schools and colleges should conduct a no-nonsense program to instill awareness in their students that clichés like “at the end of the day” aren’t desirable English.

Second, public officials from the national level down to the local governments should undergo an English reorientation program designed to, among others, curb their predilection for using “at the end of the day” and other dreadful clichés in public speaking engagements and media interviews.

And third, TV and radio network owners should seriously consider penalizing talk-show hosts or news anchors with hefty fines for overusing “at the end of the day” and such clichés, and to never again invite talk-show guests who habitually spout them more than, say, twice in a row during a particular show.

Only through draconian measures like these, I’m afraid, can we put an end to the plague of “at the end of the day” in college debates and in public discourse as a whole.

---------

This essay first appeared in the weekly column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in The Manila Times, January 4, 2013 issue © 2014 by Manila Times Publishing. All rights reserved.

RELATED READINGS:

Doing battle with the most irritating phrases in English

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

How to practice spoken English in non-English-speaking countries

Commentary by Mwita Chacha, Forum member (August 27, 2013):

The advice commonly given to folks fighting their poor spoken English is speak, speak, speak. Such a suggestion makes a great deal of sense if the learner lives in an English-speaking country. It becomes unrealistic, however, for someone in a country like Tanzania, where English speaking is restricted to a very small number of people. Extremely tough is to encounter a person on the streets of Dar es Salaam, our capital, talking English to another person—let alone perfect English.

I am fortunate to have been sent to an elementary school in neighboring Kenya. Kenya is a former colony of Britain like our country. But unlike our country’s first president, its president didn’t abolish the use of English as a teaching language in primary schools. It was during my time there that I became somewhat capable of speaking the language confidently. That happened between 1996 and 2002, and the benefits are unfolding today at the university and they certainly will further reveal themselves in the future.

I managed to be enrolled there because my parents were happy to pay for my school fee. Both of them can be described as belonging to what one can call a class of educated citizens, so they may not need to be lectured about the importance of English speaking skills in the integrated globe. An itinerant biology lecturer, my father spends much of his time traveling around the world delivering lessons in different universities. He also has taken part in several academic conferences, being involved as a speaker or a moderator. My mother, a spokesperson at a government institution, issues press releases and holds meetings with reporters to explain issues related to her office almost every single day. She is now preparing to open an evening class that will be dedicated to helping the wannabe information officers to become familiar with the kind of job they’re about to do. In short, my parents thought nothing of expending a total of USD 4,000 (it was quite a huge sum then) on the school fee for my seven years at the Kenyan school.

My parents are sort of privileged. Not all parents in Tanzania get a level of education or exposure similar to theirs; in fact, there are more than 20 million of adult people without a college degree in the country of over 40 million people. To such people, knowing English language is not more important than having a good command of any other local language.

But for those who realize that the usefulness of a good grasp of English language can’t be underestimated, the challenge is always there. Foreign English-medium schools charge such high fees that many parents literary can’t afford them and so dismiss all hopes that their children can be enrolled. For instance, the school I attended now wants parents to pay USD2,000 per year of studies, and it isn’t even close to the country’s first-rate schools. So the amount might be twice as much as that charged by comparatively better schools. In a country where the minimum wage is less than USD130, telling parents to make such exorbitant payments comes close to saying to them that their children are not needed in those schools.

But these children certainly have to become fluent in spoken English to survive the forces of the modern world. Everywhere English is becoming an increasingly demanded language. U.S. and European colleges don’t register students who are not conversant in spoken English. Foreign multinational companies operating in our country make it as a criterion that their potential employees must be familiar with spoken English. Ironically, even local employers also demand that jobseekers be at home with spoken English. Surely, a precise understanding of the King’s language is a must in today’s highly competitive society. And to achieve that, one has to speak, speak, speak. But how does one do it if he or she is surrounded by people who can’t speak?

Response by Nicky Guinto, Forum member (August 28, 2013):

Hi Mwita Chacha,

I perfectly understand your situation for I myself have to learn a foreign language (i.e., German, which is not widely spoken in the Philippines) as part of the requirements for my graduate studies. Even though I have a basic understanding of the language system of Deutsch, as Germans call it, I can hardly find someone to talk to so I can practice using the language.

You are right when you said that for you to learn a language, you need to use it and that otherwise you’ll lose it. That’s how language learning works as proven by respected scholars in the field and in innumerable research conducted in this area. A reading competence in a language, especially in English at this day and age, is inadequate if your goal is to reach an international audience. This competence must be transformed into the much-needed productive skills (i.e., speaking and writing) if one wishes to partake in the global trade and industry. The only way to do this to exhaust all means possible to use the language even if the environment is not supportive of your goal.

I tried to read a few things about Tanzania on the Internet and it’s interesting to find out that your language policy specifically assigns Swahili as a preferred language for local and national identity, and English (being a de facto language in certain institutions) for global participation. I find this supposed “fact” (as my source suggests) about your country contrary to what’s really happening in your area based on your case. I wonder how such a policy works in your country.

Nonetheless, I’d like to share a few tips with you that actually worked with people I know.

First, and I guess you might have already tried this, is to use the power of the Internet to practice using the language. I remember a friend who had to learn Spanish for his foreign language exam despite not taking any formal courses on Spanish; he was able to pass the test all because of his six-month effort to view YouTube tutorials and free practice exercises offered by different websites. Since we’re talking about English here, it wouldn’t be that much of a problem since 70% of websites on the Internet are in English and I would like to believe that more than half of YouTube content is in English.

Second is to find a friend (the easiest way being on the Internet through different platforms) whom you can talk to about random everyday things at a certain time of the day or week when both of you are available. For example, I met a friend in China who is trying to learn English and she asked me if it’s ok that we become buddies in WeChat (a mobile application that can be used for chatting). Of course I said yes and from then on, we have been constantly sending messages to one another. Just last week, I met a Japanese who is also trying to learn English and before we parted ways, he asked for my Facebook account so we can be constantly connected, although, of course, one of his goals is to have someone to talk to (or perhaps write to) in English when he returns to Japan.

Third is to attend international conferences, not just to add to your credentials, but also to seek connections and forge friendships with foreign nationals. I’ve attended several international conferences and they have indeed opened wider doors for academic collaborations and many other possibilities in my case.

Finally, talk to yourself in English when absolutely no one is available to practice with you. But please do this when you're alone because you don’t want to be mistaken to have psychological problems or whatnot. It worked for me. I not only learned more about myself through periodic reflection, but in the process, I managed to improve my conversational English (as far as I believe).

Of course, there are many other ways that may absolutely work for you. One thing you have to remember though is that it’s alright to commit mistakes while learning the language. Sometimes, people including my students refuse to speak in English for fear that the person they are speaking with will size them up based on the kind of English they speak; this results in lack of confidence to actually use the language. This should not be the case because, after all, everyone will commit mistakes no matter how good he or she is in the language. If you happen to make a mistake while conversing with someone, ignore the fact that you made it. What is important is for you deliver your message across, and that you are aware that you made a mistake so that in the future, you can avoid doing it again.

In my experience, I found that it doesn’t matter what variety of English you speak or whether you speak the language in a way far different from the dominant varieties (i.e., British or American) as long as they get what you mean. This is because they will be delighted by the fact that despite your cultural differences, you actually tried talk to them in a language familiar to both of you.

I hope this helps.

Regards,

Nic Guinto

Rejoinder by Mwita Chacha (August 31, 2013):

I appreciate the methods you’ve provided, bibliosense, to be taken into consideration by someone ambitious to become fluent in spoken English but fails to practice speaking it because he or she is living in a country where there are not enough people capable of speaking the language and therefore not enough people to speak with. Although in my Third World country the Internet connection obviously isn’t as widespread and readily available as in the Phillipines, I still think that many of the academic institutions have access to the service (as the government wants them to have it as a condition to get permission to start business), and students and staffers alike in such places may want to make it a point to carry out your suggestions if they are serious about getting a good grasp of the Queen’s language; that way, they will be able to compete in this incredibly English-demanding world and communicate confidently with people whose only language is English.

But one thing before I go: Your writing style looks so strikingly similar to that of Jose Carillo that I almost thought he had signed in under a different username. I wonder if this is an outcome of a deliberate effort or is merely a coincidence. I am curious about that because I myself have a massive soft spot for his style and, over several months, have been trying to go through the archives of his past postings to see if I might be able to discover the secret behind his compelling writings. This task unfortunately hasn’t been as easy as I had thought; nevertheless, I haven’t lost hope that I someday will be able to achieve that. Now if indeed you managed to attain that through some kind of an effort, please tell me why it has been a breeze for you to bring off what seems to me a somewhat highly elusive goal.Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting

Retrospective: Did Rizal ever speak and write in English?

On the occasion of Dr. Jose P. Rizal’s 151st birth anniversary last June 19, 2013, the Forum decided to repost this very interesting discussion on whether the Philippine national hero ever spoke or wrote in the English language.

Forum members with more insights about this aspect of Rizal’s life are invited to share them and continue this discussion.

Question by paul_nato, Forum member (January 28, 2010):

I don’t know if this is the right place to ask this question, but…

I know our national hero Jose Rizal wrote and spoke many different languages, such as Spanish, German, and French, but I was wondering if he also spoke and wrote in English.

I don’t remember reading or hearing anything about it in class. Admittedly, I might have been absent, or I was asleep when it was discussed.

My reply to paul_nato (January 29, 2010):

You’ve come to the right place, paul_nato! The Students’ Sounding Board is the place to discuss anything about English that baffles you—and that includes not just English grammar and usage but also vignettes in the history of the English language, its literature, and its acquisition and use by nonnative English speakers.

Now to your question on whether Jose Rizal also spoke and wrote in English…

Most of his writings were in Spanish, of course, and several others were in Tagalog. He used Spanish to write his landmark novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, the poem A La Juventud Filipina (To the Filipino Youth) that he wrote when he was 18 and the poem Mi Ultimo Adios (My Last Farewell) that he wrote on the eve of his execution, and many of his essays and articles for periodicals. And he used Tagalog to write the poem “Sa Aking Mga Kababata” (To My Fellow Youth) when he was only eight years old, some essays, and many of his letters to family members, friends, and associates in the Philippines. I think we can confidently say that Rizal was not only very fluent but very prolific as well in both Spanish and Tagalog.

As to English, I’m not aware of any major work that Rizal originally wrote in English. My understanding, though, is that he spoke a smattering of English and French, particularly during his studies in Spain and his sojourns in various places in Europe. I came across a passing mention in an account of his life--probably apocryphal--that Rizal had told some foreign acquaintances in Europe that he had begun to study English seriously. According to the account, he wanted to polish his English at the time because “he was seriously trying to win the love of an Englishwoman.” This was most likely during his stay in London from 1888-1889.

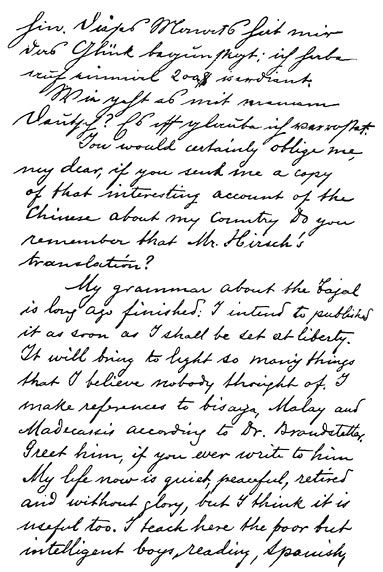

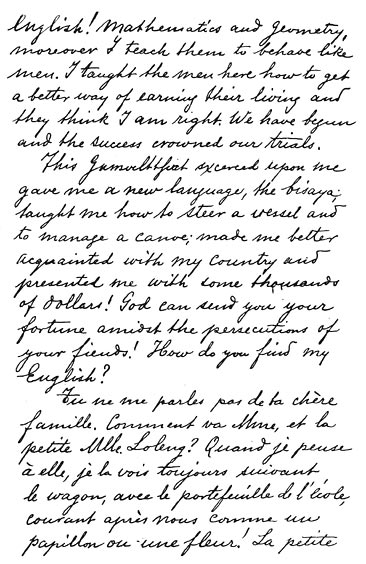

Although I gather that he didn’t write professionally in English, I came across convincing evidence that he was adequately proficient in using it at least for personal correspondence with friends who were conversant in English. Below is a portion of a facsimile of a letter he wrote in beautiful longhand in three languages—German, English, and French—to express his condolences to his friend Ferdinand Blumentritt, a German teacher and secondary school principal, on the death of Ferdinand's father. The letter was written on July 31, 1894 in Dapitan, where Rizal was then on exile for alleged subversive activities against the Spanish government.

In the letter, Rizal first writes in German to express his condolences, then shifts to English at some point:

Here’s a transcription of the English portion of that letter:

“You would certainly oblige me, my dear, if you send me a copy of that interesting account of the Chinese about my country. Do you remember that Mr. Hirsch’s translation?

“My grammar about the Tagal is long ago finished. I intend to publish it as soon as I shall be set at liberty. It will bring to light so many things that I believe nobody thought of. I make references to bisaya, Malay, and Madecassis* according to Dr. Brandstetter.** Greet him, if you ever write to him

“My life now is quiet, peaceful, retired and without glory, but I think it is useful too. I teach here the poor but intelligent boys reading, Spanish, English! Mathematics and Geometry, moreover I teach them how to behave like men. I taught the men here how to get a better way of earning their living and they think that I am right. We have begun and the success crowned our trials.

“This Gewaltthat*** exerted upon me gave me a new language, the bisaya; taught me how to steer a vessel and to manage a canoe; made me better acquainted with my country and presented me with some thousands of dollars! God can send you your fortune amidst the persecutions of your fiends! How do you find my English!”

[From here he begins to write in French]

Based solely on this letter to his friend Blumentritt, my opinion is that Rizal was quite proficient in English, comfortable using some of its idioms, and competent in constructing even oblique expressions in English. He was evidently still self-conscious with his English; we can see this in his use of the exclamation mark after the word “English” when he told his friend that he was teaching the language, and when, apropos about nothing, he abruptly writes “How do you find my English?” He also committed a spelling error in one instance (“fiend” for “friend”).

As to his English grammar, here’s how I would have advised Rizal had he consulted me about the English of his draft letter:

1. “Do you remember that Mr. Hirsch’s translation?” This is an awkward use of the adjective “that” for emphasis. Better: “Do you remember that translation of Mr. Hirsch?” Alternatively: “Do you remember the translation of that Mr. Hirsch?”

2. “My grammar about the Tagal is long ago finished.” The use of the present tense “is” in this sentence is in error. Corrected: “My grammar about the Tagal was long ago finished.” Much better in the active voice: “I long ago finished my grammar about the Tagal.”

3. “I teach here the poor but intelligent boys reading, Spanish, English! Mathematics and Geometry, moreover I teach them how to behave like men.” Rizal doesn’t seem to know how to deal with the conjunctive adverb, particularly “morever.” Structurally, “moreover” needs a semicolon before it and a comma after it. That sentence as corrected: “I teach here the poor but intelligent boys reading, Spanish, English, Mathematics and Geometry; moreover, I teach them how to behave like men.” (Stylistically, so that the flow of the exposition won’t be disrupted, it would be much better to set off the exclamation mark after “English” with parenthesis: “English (!)”.

4. “We have begun and the success crowned our trials.” This sentence suffers from the rather awkward phrasing of “the success crowned our trials.” It will read much better if the definite article “the” is dropped and the present perfect is sustained for the second clause: “We have begun and success has crowned our trials.”

5. “This Gewaltthat exerted upon me gave me a new language…” Here, Rizal’s use of the word “exerted” wasn’t very well-chosen; “imposed” would have been more appropriate semantically: “This Gewaltthat imposed upon me gave me a new language…”

Overall, though, Rizal was definitely above-average in his written English. His facility with written English could put many of us to shame considering that he was essentially self-taught in English while we are formally taught English grammar and usage from grade school onwards.

-------

*According to some historians, Rizal probably meant the Malagasy language here.

** Dr. Renward Brandstetter (1860-1942) was a Swiss linguist who studied the insular Malayo-Polynesian languages

***Gewaltthat – German for “act of violence, atrocity”; an oblique reference to Rizal’s exile in Dapitan by the Spanish authorities.

Primary source: Lineage, Life and Labors of Jose Rizal: Philippine Patriot by Austin Craig

LINKS:

A La Juventud Filipina (To My Fellow Youth)

Mi Ultimo Adios (My Last Farewell)

Sa Aking Mga Kababata (To My Fellow Youth)

COUNTERVIEW. Dr. Jose Rizal didn’t write the poem “Sa Aking Mga Kababata,” Forum member justine aragones wrote in the Forum’s Lounge section last June 20, 2013. Read justine aragones's posting now!

MORE DISCUSSIONS FOLLOW

Join and continue the discussions!

Click to post a comment or view the comments to this posting