- HOME

- INTRO TO THE FORUM

- BADLY WRITTEN, BADLY SPOKEN

- GETTING

TO KNOW ENGLISH - PREPARING FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TESTS

- GOING DEEPER INTO ENGLISH

- YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

- EDUCATION AND TEACHING FORUM

- ADVICE AND DISSENT

- MY MEDIA ENGLISH WATCH

- STUDENTS' SOUNDING BOARD

- LANGUAGE HUMOR AT ITS FINEST

- THE LOUNGE

- NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

- ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

- No Earthly Reason Why The Clergy Should Be Bad In English Grammar

- Here’s Hoping For Better English In This Year’s Graduation Rites

- Looking Back to Easter Sunday’s Earthly and Celestial Foundations

- Our Need For Thinking National Leaders With The Gift Of Language

- The Heavy Price of Misplacing One’s Trust and Confidence

- The Three Basic Word-Positioning Principles For Emphasizing Ideas

- ABOUT JOSE CARILLO

- READINGS ABOUT LANGUAGE

- TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

- NEWS AND COMMENTARY

- BOOKSHOP

- ARCHIVES

NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

This page features outstanding works of Filipino writers in English, both past and present. Whenever the need or opportunity arises, a notable work—whether essay, speech, short story, poetry, play, or excerpt from a novel—will be presented here either in its full text or through a link to a website that carries it.

I hope you’ll not only enjoy the offerings of this series but also learn from their felicitous use of the English language!Jose Carillo

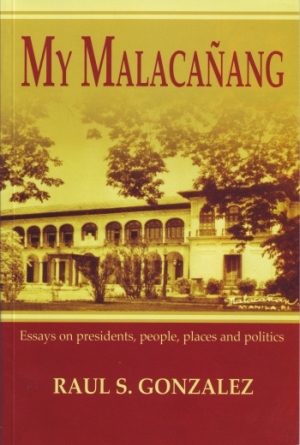

Tales of the longest-staying Malacañang resident except for one

By Jose A. Carillo

From its beginnings in 1802 as a Spanish aristocrat’s summer home, Malacañang Palace in Manila was to become the prime seat of political power in the Philippines. It served as the official residence of the country’s governors-general both during the Spanish colonial years until 1898 and during the American occupation until the establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth in 1935. From then onwards it was to be the official residence of 12 successive presidents of the Philippines1—Manuel Quezon, Sergio Osmeña, Manuel Roxas, Elpidio Quirino, Ramon Magsaysay, Carlos Garcia, Diosdado Macapagal, Ferdinand Marcos, Corazon Aquino, Fidel Ramos, Joseph Estrada, and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

For all their political power, however, all 12 were simply short-term tenants of Malacañang under the country’s democratic system. Each took residence there for at most a four-year or (later) six-year stay, and could look forward to the possibility of staying longer only if reelected. Indeed, only two managed to stay in Malacañang for more than one term—Marcos, who won a second four-year term and managed to extend his stay to a total of 21 years through the expedient of martial rule; and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, former Malacañang tenant Diosdado Macapagal’s daughter, who succeeded Estrada as president when the latter was ousted after only 30 months in residence, then managed to extend her own tenancy for another six years—a term that, of course, brings us to the present day. (Three of the official Malacañang tenants died during their tenancy: Quezon in 1944 and Roxas in 1948, both from illness, and Magsaysay in a plane crash in 1957.)

Today, a total of nine presidential candidates want to become Malacañang’s official tenant for the next six years—among them Joseph Estrada, the ousted Philippine president who wants to reclaim Malacañang to vindicate his name; Senator Benigno Aquino III, son of previous Malacañang tenant Corazon Aquino; and Senator Manuel Roxas II, grandson of former Malacañang tenant Manuel Roxas, who, as Noynoy Aquino’s running mate, puts himself in a contingent position to be also a Malacañang tenant. How the political winds will blow in the national elections this coming May will, of course, determine whether that tenancy would be handed over and revert to any of the same families that had previously occupied Malacañang, or go to the serious contenders for first-time occupancy—Senator Manuel Villar, Jr., Senator Richard Gordon, and former Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro, Jr.

Longer-staying Malacañang tenant than most

Through all the often fierce jockeying for residence in Malacañang over the years, however, one man had largely kept mum about the fact that that he had been a longer Malacañang resident than any of the Philippine presidents—except one. This was until that former long-time resident, Raul S. Gonzalez, came out last November with a superb memoir-cum-essay collection, My Malacañang: Essays on presidents, people, places and politics, where he blithely asserts in the very first sentences of the very first chapter: “Except for Ferdinand Marcos, no president of the Philippines lived in Malacañang longer than I did. You read it right—‘than I.’ And yes—‘lived,’ as in resided, ate, drank, slept, wakened, thought, dreamt, fell ill, got well, played, laughed, wept, prayed. And yes, yes—‘longer,’ 12 or 13 years.”

Raul S. Gonzalez: Author of My Malacañang

Who, one may ask, is this Raul Gonzalez2 who can refer so familiarly and so nonchalantly to a stately place of residence—a palace, in fact—that many an ambitious Filipino would fight for and die for and likely even lie for just for a six-year stay?

To be sure, Gonzalez had actually been a non-elective Malacañang resident. He used to live in a chalet within the Malacañang compound because his father, architect Arturo M. Gonzalez, was appointed by Philippine Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon sometime after 1935 as Malacañang’s buildings and grounds superintendent. Architect Gonzalez held the position until his violent death inside Malacañang grounds in December of 1949.

Strong sense of ownership over the place

The younger Gonzalez himself sums up his strong sense of ownership over Malacañang in the first chapter of his book: “Malacañang was where I took my first firm steps and uttered my first coherent words, where I rode my first bike, read my first book, stole my first kiss, wrote my first poems. It was, I might add, also in Malacañang where I saw what war did to men and what men did in war, in Malacañang where two sisters of mine were conceived and [where] my father bled to death in my 15-year-old arms from a bullet fired from a crazed soldier’s browning automatic rifle, Malacañang which shaped me into the person I am.”

This amazing facility with English prose is vintage Raul Gonzalez, a now-retired communications executive and writer who’s an English-language wordsmith with few equals in the Philippines. His career, spanning several decades until the late 1990s, included a stint in government as press secretary of the late President Diosdado Macapagal and as senior vice president of the Government Service Insurance System; in academe, as vice president of university relations of the University of the East; and in the mass media, as beat reporter for the now-defunct Manila Chronicle in the 1950s and, in the 1990s, as opinion columnist for the Philippine Star and The Daily Tribune. He had also served as public relations adviser and speechwriter for some prominent public figures in the Philippine scene.

In My Malacañang, Gonzalez writes with elegant, sometimes almost rhapsodic prose about life in the old palace by the Pasig River, about Philippine society and politics in general, and about the movers and shakers he had served or had met in the course of his career as communications executive and writer.

Listen to Gonzalez reminisce in My Malacañang about summer of ’45 at the end of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines:

“MacArthur returned not a moment too soon, an eternity too late. Our fast had lasted three long years, almost unto starvation, and turned us children in Malacañang into grotesqueries—looking like gnomes and salamanders, eyes bulging out of their sockets and cheeks sunken and hollow, limbs without flesh and stomachs bloated by hunger, some of us so ravaged by beri-beri that taking a single step was almost like carrying the cross up Calvary.

“Yet we, starvelings all, found soon enough and quickly learned that we could only munch so many apples, chew only so much gum, gulp down only so much Coke, gobble up only so many Babe Ruths and Tootsie Rolls.”

A life-changing encounter with death

And here’s Gonzalez summoning from memory his terrible, life-changing encounter with death in Malacañang:

“The soldier fires, and I see Father knocked off his feet and flung a yard away, a perplexed look on his face, a half-smile playing on his lips. He has always been elegant—Father, that is—and he rights himself and like a leaf whose autumn has come, falls slowly, gently, gracefully to the ground…

“I rush to where my Father is, cradle him in my arms, and he looks at me with those eyes of his that even in anger never stop smiling, and I see a wet, red spot on his necktie getting larger and larger and larger. ‘Help him,” I cry, “Help him.’

“Hands—I don’t know whose—pull Father out of my embrace but, to this day, I can feel his weight, his warmth, and his blood oozing out of him as he lay dying in my arms on the earth of his Malacañang.”

Gonzalez as press secretary to Philippine President Diosdado Macapagal, early 1960s

Many years after his father’s death, Raul Gonzalez was to become a non-elective Malacañang resident again—if only on a day-job basis—when he was appointed press secretary by President Diosdado Macapagal. After Macapagal gave way to Ferdinand Marcos as the new official Malacañang tenant in 1965, Gonzalez worked with the private sector and wrote off and on as an opinion columnist for some Metro Manila broadsheets. In 1986, under the government of then Malacañang tenant President Corazon Aquino, Gonzalez was named GSIS vice president for public relations, a position he held until 1998 under the Malacañang tenancy of President Fidel Ramos.

Insights from the corridors of power

His having walked and worked in the corridors of political power gave Gonzales deep, unparalleled insights about the workings of government. Listen to his philosophical rant in his newspaper column in 1995 about the inefficiency of government:

“Indeed, a lean bureaucracy is a contradiction in terms, as oxymoronic as military intelligence…Thus, where private industry, which is motivated 95 percent of the time by the desire for profit, tries to make do with as small a complement of personnel as it can get by, the government, which is motivated 100 percent of the time by the desire for power, tries to make out with as large a bureaucracy as it can get away with.

“Private industry will make one man perform 10 different tasks, but government will make 10 men perform one and the same task. Put another way, private industry fills a job so that it may be done; government creates a job so that it can be filled. Or better yet, private industry will fill a job only when it is necessary for the purpose; whereas government will create a job because it is necessary to its purpose.”

A keen eye for high achievers

Gonzalez had a keen, discriminating eye for high achievers among people—particularly for young student writers in that often awkward, self-conscious stage of growing their creative wings3, but even for the adult high achievers who had already proven their executive and leadership mettle by winning the tenancy of Malacañang itself. Here, for example, is his recollection of President Fidel Ramos in mid-1996 after the latter’s round of golf at Malacañang Park:

“He still has a wide-eyed reverence for excellence, especially athletic excellence. He looked at [German ace golfer Bernhard] Langer with a respect I hardly see him accord other men; the same look he gives Luisito Espinosa, Elma Muros, Robert Jaworkski4.

“He takes a child-like delight in leaving things looking better than when he found them. He couldn’t stop talking about the improvements he had worked in the park and the place itself. ‘You grew up here,’ he said. ‘Come more often and take a longer, closer look at what I have done.’”

Gonzalez with former Philippine President Fidel Ramos during

the launching of My Malacañang in Manila, November 5, 2009

But the usually mild and soft-spoken Gonzalez could also be savagely indignant and bitingly sarcastic with his prose, although often in high magisterial style. Here’s what he wrote in his 1995 newspaper opinion column about popular Philippine comedian Dolphy’s response to his fans who were then egging him to take a stab at high public office:

“Paano kung manalo ako? [What if I win the election?]

“The question Dolphy asked himself is a question no one who aspires to an elective office should fail to ask himself, preferably as soon as the political bug bites and even before the itch to run develops: Paano kung manalo ako? It is not that an honest reply to this question may ensure that our government will not be run by dogs—worse yet, by curs—that got lucky and caught a car. That is simply being patriotic. It is, rather, that Dolphy’s question may stop people less knowledgeable or less honest about themselves than Dolphy from spending the next six years of their lives scurrying from one rat hole to another in the effort to keep their nincompoopery concealed, private, and known only to their mothers. That is surely being kind to oneself.”

When giving vent to his opinions, Gonzalez could throw caution to the winds, too—even get stylishly snarky or snarkily stylish—as in this passage from his August 1990 newspaper column defending President Cory Aquino when the media tide began to wash against her:

“…it takes only one word to explain…why a media contract is out on Cory, why there’s a policy of againstness on her, why the tales against her are bound to grow taller, wilder, dirtier. The word is: Fear. Fear that she just might run. And if she does, paano naman kami?

“There’s no one in the Opposition now who can beat Cory—and all the polls show it; this despite the ravings and rantings dutifully, and sometimes gratuitously, reported by media about how uninspired her leadership is, how inept her Cabinet members are, how gosh-awful her giggling last July 16 was…”

Flesh-and-blood sketches of people in power

Except for a few touching, sometimes overly sentimental vignettes about Gonzalez’s personal and family life in the latter part of the essay collection, My Malacañang largely devotes itself to perceptive, flesh-and-blood sketches of the men and women—and their surrogates as well—who had tenanted Malacanang over the past 74 years. He weaves quick, arresting tapestries of their virtues, foibles, and quirks: the imperious Manuel Quezon, “with his short fuse and low boiling point,” unleashing his trademark “puñetas” on those who dared cross him; Carlos Garcia, “the most placid and serene president,” who was probably made so “by composing ‘balak,’ Boholano poetry, and playing chess to the exclusion of anything else”; Diosdado Macapagal, with his almost mystical respect for the Filipino, but who “lacked the charm to convince the people of the sincerity of his intentions,” thus leading to his political undoing; Ferdinand Marcos, “too calculating to allow himself the luxury of genuine anger” and one who “never uttered any word, made any gesture, showed any expression that had no conscious purpose”; Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, possessing “considerable charms,” but with a temper “hair-trigger in its sensitivity and thermonuclear in its explosiveness”; Cory Aquino with her Noah-nesque kind of political leadership, “unshakable in her faith that everything depends on God”; and Joseph Estrada, whom he likened to the Biblical Samson, “a huge man with a big heart and no guile at all, [who] preferred the simple pleasures and the merry company of commoners.”

Here, indeed, is the essential Raul Gonzalez, an astute observer writing with the confident, sure-footed voice of a consummate English-language stylist. His singular experience of having been the longest-staying non-elective resident of Malacañang had given him a ringside seat to recent Philippine history and contemporary events. And many of his essays in My Malacañang sparkle in his highly engaging narrative and expository style, some even rising to the level of great, unforgettable prose, as in this vaulting passage about the Filipino mentality of “puede na”:

“Name me, show me any bug in the systems we employ, any defect in the goods we produce, any deficiency in the service we render, any blemish in the leaders we choose, any kink in the armor we don, any fly in the ointment we prepare, any flaw in the way we think, comprehend, decide, act—and, believe you me once more, it can be traced to how easily either these two phrases—puede na or puede pa—comes to the Pinoy lips and moves the Pinoy mind…

“Puede na I blame as the culprit for the mediocrity that the Filipino has become. It is what has held us back as a people despite the agility of our mind, its inventiveness, its thrusting nature; despite the beauty and bounty of our land; despite so many good starts; despite the fact that we have always been pathfinders and trailblazers, first in many things—to drive out our colonizers, to gain political independence, to absorb the ways of the West.”

Truly, Raul Gonzalez’s 65 essays in the 320-page book make My Malacañang not only a highly evocative and compelling set of cautionary tales about life and politics in the Philippines but also superb, instructive reading for students of style and rhetoric in English.

Copyright © 2010 by Jose A. Carillo. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information on reprints, please send e-mail to the author at josecarillo@skybroadband.com.ph.

----

1Jose P. Laurel was president of the Philippines during the Japanese Occupation from 1942-1945 but, based on Raul Gonzalez’s first-hand account in My Malacañang, never took up residence in the palace, preferring to always sleep in in his house in Peñafrancia St. in Paco, Manila.

2Raul S. Gonzalez the writer and communications executive is not the same Raul M. Gonzales the former Philippine justice secretary.

3From the late 1960s up to the mid-1970s, Raul S. Gonzalez was adviser of the college student newspaper of the University of the East, with a circulation that grew to over 65,000 copies weekly.

4Luisito Espinosa, Elma Muros, Robert Jaworkski were at the time the leading Filipino athletes in professional boxing, running, and basketball, respectively.

Read Alfred Yuson’s earlier review of My Malacañang in the Philippine Star

Read Leandro Coronel’s earlier review of My Malacañang in the Business Mirror

My Malacañang by Raul S. Gonzalez (DAWN Alumni and Writers Network, publisher, © 2009: 320 pages, coated bookpaper) is a limited edition that’s not available in bookstores. Cover price is PhP500, plus PhP84 for domestic delivery in the Philippines via Air21. For orders and more delivery details, contact either of the following: Tel. (632) 726-8545, e-mail raulsgnzlz@yahoo.com; or Tel. (632) 811-2140, Mobile 0917-5220623, email second_opn@yahoo.com.

View the complete list of postings in this section

(requires registration to view & post)