- HOME

- INTRO TO THE FORUM

- USE AND MISUSE

- BADLY WRITTEN, BADLY SPOKEN

- GETTING

TO KNOW ENGLISH - PREPARING FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TESTS

- GOING DEEPER INTO ENGLISH

- YOU ASKED ME THIS QUESTION

- ADVOCACIES

- EDUCATION AND TEACHING FORUM

- ADVICE AND DISSENT

- MY MEDIA ENGLISH WATCH

- STUDENTS' SOUNDING BOARD

- LANGUAGE HUMOR AT ITS FINEST

- THE LOUNGE

- NOTABLE WORKS BY OUR VERY OWN

- ESSAYS BY JOSE CARILLO

- Long Noun Forms Make Sentences Exasperatingly Difficult To Grasp

- Good Conversationalists Phrase Their Tag Questions With Finesse

- The Pronoun “None” Can Mean Either “Not One” Or “Not Any”

- A Rather Curious State Of Affairs In The Grammar Of “Do”-Questions

- Why I Consistently Use The Serial Comma

- Misuse Of “Lie” And “Lay” Punctures Many Writers’ Command Of English

- ABOUT JOSE CARILLO

- READINGS ABOUT LANGUAGE

- TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

- NEWS AND COMMENTARY

- BOOKSHOP

- ARCHIVES

Click here to recommend us!

TIME OUT FROM ENGLISH GRAMMAR

This section features wide-ranging, thought-provoking articles in English on any subject under the sun. Its objective is to present new, mind-changing ideas as well as to show to serious students of English how the various tools of the language can be felicitously harnessed to report a momentous or life-changing finding or event, to espouse or oppose an idea, or to express a deeply felt view about the world around us.

The outstanding English-language expositions to be featured here will mostly be presented through links to the websites that carry them. To put a particular work in better context, links to critiques, biographical sketches, and various other material about the author and his or her works will usually be also provided.

Science works because it feeds on curiosity and breaks its own rules

Once upon a time curiosity was considered a dangerous and condemnable vice, with deep-seated superstition or religious dogma making people believe that there are some things they shouldn’t even attempt to know. Fortunately for humanity, the rise of science from the 16th through the 18th centuries—a time that spans the lives of Galileo and Isaac Newton—eroded this wrongheaded paradigm and made inquisitiveness a virtue rather than a vice.

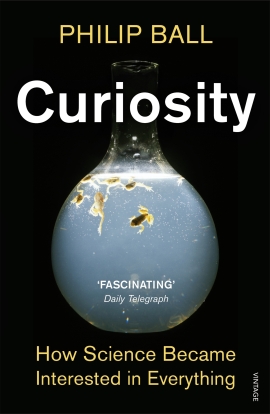

In his new book Curiosity: How Science Became Interested in Everything (University Of Chicago Press, 480 pages), science writer and editor Philip Ball vividly chronicles the rise of scientific thinking and its eventual predominance in modern life. But he argues that scientific enlightenment didn’t happen as a simple, linear process; instead, he says, science emerged less through great thinkers thinking great thoughts than through the idiosyncratic experiments of thousands of independent tinkerers, inventors, collectors and flat-out oddballs.

Ball explains: “The problem is that, because science produces knowledge that is, for the most part, dependable and precise, we tend to believe there must be a dependable, precise method for obtaining it. But the truth is that science works only because it can break its own rules, make mistakes, follow blind alleys, attempt too much—and because it draws upon the resources of the human mind, with its passions and foibles as well as its reason and invention.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Philip Ball, a science writer who lives in London, worked for over 20 years as an editor for Nature, writes regularly in the scientific and popular media, and has authored many books on the interactions of the sciences, the arts, and the wider culture, among them Critical Mass, The Self-Made Tapestry: Pattern Formation in Nature, H2O: A Biography of Water, Bright Earth, Universe of Stone, and The Music Instinct. He has a BA in Chemistry from the University of Oxford and a PhD in Physics from the University of Bristol.

RELATED READINGS:

A highly desirable mutation. In “Archaeology: The milk revolution,” an article that came out in the July 13, 2013 issue of Nature Magazine, Andrew Curry writes about how a single genetic mutation allowed ancient Europeans to drink milk, thus setting the stage for a continental upheaval. Until then, milk was essentially a toxin to adults because — unlike children — they couldn’t produce the lactase enzyme required to break down lactose, the main sugar in milk. But as farming started to replace hunting and gathering in the Middle East around 11,000 years ago, a genetic mutation spread through Europe that gave people the ability to produce lactase — and drink milk — throughout their lives.

Read Andrew Curry’s “Archaeology: The milk revolution” in Nature Magazine now!

Why the humanities shouldn’t resent science. In “Science Is Not Your Enemy,” an article that came out in the August 6, 2013 issue of the New Republic, Harvard University psychology professor Steven Pinker argues that ours is an extraordinary time for the understanding of the human condition, with intellectual problems from antiquity now being illuminated by insights from the sciences of mind, brain, genes, and evolution. “One would think that writers in the humanities would be delighted and energized by the efflorescence of new ideas from the sciences,” he says. “But one would be wrong. Though everyone endorses science when it can cure disease, monitor the environment, or bash political opponents, the intrusion of science into the territories of the humanities has been deeply resented.”

Read Steven Pinker’s “Science Is Not Your Enemy,” in the New Republic now!