A fortnight ago I received e-mail that raised brief but candid questions and frank comments regarding the narratives by two 15th century European writers about the events that transpired when the Spanish Expedition led by Ferdinand Magellan anchored in Mazaua on March 28,1521 and had the first Holy Mass officiated there three days later. What happened at that time was the subject of this column’s recently concluded 21-part series on “Getting our Philippine history right after 500 years.”

Forum member Miss Mae asked in her e-mail: “I wonder if Maximilianus Translyvanus had asked for Antonio Pigafetta’s permission when he wrote a version of the narrative. The problem started with him. He may be a royal courtier and secretary to the king but wasn’t verifying one of his responsibilities? This historical mistake must also be included in the profile of Giovanni Battista Ramusio. I have grown up believing that the First Mass happened in Limasawa and a classmate or two of mine were marked wrong because they didn’t get the spelling of the place correctly.”

My reply to Miss Mae:Based on the extant historical records, I think we can be sure that neither Transylvanus nor Ramusio ever asked for Pigafetta’s permission when they wrote their respective versions of Magellan’s sojourn in the Philippine archipelago. In fact, I strongly believe that neither of them felt that they were under any obligation to discuss or verify with Pigafetta the accuracy of any of the information they presented in their own narratives.

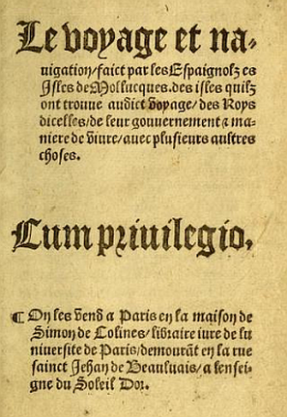

In fairness to Transylvanus, I will say this firmly: I don’t think that he was involved in starting the very troublesome problem of Mazaua’s wrongful devolution over 500 years into Limasawa as the First Mass site. Not at all. In fact, as I pointed out in my 21-part series, his

"De Moluccis Insulis” was the very first history book to put on record that it was indeed to the island of Mazaua where Magellan’s fleet was driven by a storm that fateful day in 1521. However, Transylvanus did not dwell at all about what Magellan did during his seven-day stay in Mazaua, for his primary objective for writing his book was to beat everybody else in publishing the very first account about the first circumnavigation of the world.

We must keep in mind that in their time, both Translyvanus and Ramusio were wealthy, well-informed, discerning, and powerful individuals in their own right. Transylvanus, who openly aspired to be a great writer someday, was a trusted royal courtier and secretary to Spain’s King Charles V, who as the Holy Roman Emperor just happened to be the most powerful man in Europe. Ramusio, son of a magistrate of the Venetian city-state, had a long record in the Venetian public service himself and had already notched an impressive track record as geographer and travel writer.

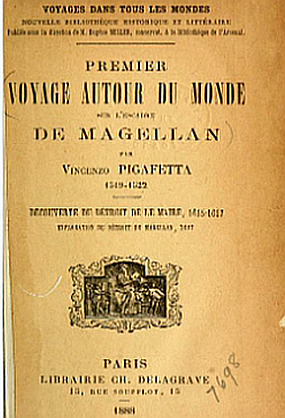

For all of these reasons, I don’t think Translyvanus and Ramusio ever deigned to even meet or talk to or even get to know Pigafetta, who at that time still had no track record as a writer, and much less was he a historian of any consequence. Pigafetta also belonged to a rich family and in his youth had studied, astronomy, geography, and cartography, but we must remember that he never got his

Report on the First Voyage Around the World decently published during his lifetime. Only 275 years later did Pigafetta attain prominence, but only posthumously, when the long-lost manuscript of his Magellanic voyage chronicles was recovered by the ecclesiastic-scholar-scientist Dr. Carlo Amoretti by happenstance at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan in 1797.

As for Ramusio’s role in the confusion about the First Mass site, we will discusss it as objectively as we can in next week’s column.

(Next:

Did the First Mass historians ever talk to one another? - 2) September 23, 2021

This essay, 2063rd of the series, appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Campus Press section of the September 16, 2021 Internet edition of The Manila Times

,© 2021 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved. Read this article online in

The Manila Times:

Did the First Mass historians ever talk to one another? - 1To listen to the audio version of this article, click the encircled double triangle logo in its online posting in

The Manila Times.