1

Lounge / A Eulogy for My Father, Eduardo Buenaventura Olaguer

« on: August 27, 2017, 01:35:49 AM »

My father is a well-known figure stemming from his days as a freedom fighter during the martial law era. His reputation as a hero is well-deserved, and as his first-born son, I am proud of his exploits on behalf of justice and truth. But there are others who know him in that capacity better than I, for during those years, I was mostly abroad and far from the scene in which the critical events played out. Instead, I would like to speak of my father in a more personal vein.

I will first describe Papa in the context of a journey that we all took as a family during 1970 to 1972, prior to the declaration of martial law in the Philippines. At that time, my father was a scholar at the Harvard Business School. He had been sent to Cambridge, Massachusetts by IBM, as a stepping stone to greater responsibilities within the company. Although Harvard is certainly a demanding institution, my father’s time apart from the corporate rat race gave us a chance to experience life in a different way. During this time, Papa saw to it that we, his children, had a rich set of experiences from which to draw for the rest of our lives.

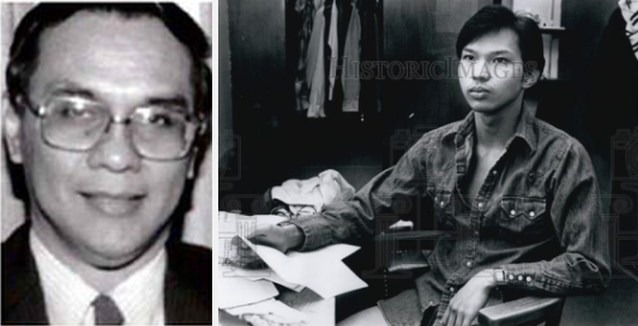

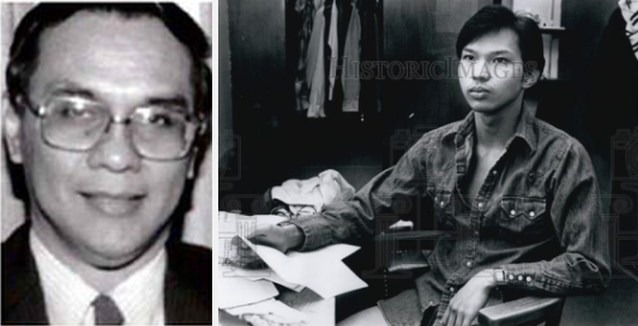

Left photo: The author’s father, Eduardo B. Olaguer, then 44, was a geodetic engineer and professor at the Asian Institute of Management (AIM). Right photo: Jay Olaguer, then 20, was at the time an undergraduate Physics major in the United States. The photo was taken when Jay was interviewed by a Boston media reporter soon after his father was arrested in December 1979 along with several others for alleged subversion against the Philippine martial law government of then President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

I remember especially the long cross-continental summer trip that Papa instigated, some of which I would later retrace with my own children. I remember that he took my siblings and me to Fenway Park to watch the Red Sox play the Baltimore Orioles, the year the latter team was destined to win the World Series, and to the Boston Garden, to watch the Celtics play, when Dave Cowens and John Havlicek were still in their prime. I remember that Papa, my brother Eric, and I, would animatedly watch TV to see Bobby Orr and the big bad Bruins take on the rest of the National Hockey League on their way to a Stanley Cup in 1972, just before we left the States to return to the Philippines. I also remember the camping trips that Papa would take us on, including one to October Mountain State Forest, during which my sister, Didi, and I got lost following the wrong trail and ended up hitchhiking back to the family campsite. My father did not berate us then, as I had expected, but merely let us learn from our own mistakes.

With regard to the life of the mind, I remember the military history books Papa would buy, which he let me read while still a pre-teen, and which made deep and lasting contributions to my intellectual development. These were books like Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August, about the outbreak of the First World War, and a survey entitled, The Wars of America, which included a description of the so-called Philippine Insurrection, which deeply upset me along with another book on a similar subject entitled, Little Brown Brother. Indeed, I read many selections from Papa’s personal library, even strange and highfalutin books like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s The Divine Milieu, with which I would later disagree. This is one reason why, to this day, I hoard books like a precious treasure trove of knowledge and insight, in the hope that my own children and grandchildren will derive a similar love of learning.

When we returned to the Philippines in 1972, political events cast a shadow on our family life. I remember my father taking me, then thirteen years old, to a talk by former Justice Barrera of the Philippine Supreme Court, warning us of the loss of freedoms that martial law would bring. I would later learn that other controversial figures, some of whom we read about in the newspapers, would show up at our home in the middle of the night. My father would eventually resign from IBM due to his political stance. For some time, my parents continued to send us to exclusive schools, despite the fact discovered by my brother, Eric, that their bank deposit book showed a near-zero balance. But my father was a man of faith, a faith which God vindicated when Papa eventually took on a series of jobs that made him a leader in the business community.

As many of you in the audience know, the Light a Fire Movement that Papa helped to found landed my father in prison for over six years. In 1983, on a summer visit home from the States where I was by then a graduate student, I had the privilege of sneaking an overnight visit with Papa in his jail cell at Bicutan. That visit was the seed of my conversion back to the Catholic faith of my youth, facilitated by some heartfelt dialogue with my father on some very deep subjects, both personal and philosophical.

Fast forward to December 2014, when I was called home due to the discovery of an aneurysm in Papa’s chest, for which he required emergency surgery. Believing that it might be my last chance to see my father alive, I wrote him the following message prior to my visit:

Dearest Papa,

It’s been a long time since I’ve written a formal letter. Since I was informed of your upcoming heart surgery, it occurred to me that time was running out for saying certain things that needed to be said. We are both advancing in years, and neither of us is in the best of health. Moreover, events in the world are rapidly coming to a head. Who knows what the future holds?

The bottom line is that I have never properly expressed my gratitude to you for certain fundamental things in my life, and I did not want the opportunity to pass in order to finally come out and say it. After raising my own children, I am sure that there are some things that they will not likely ever know, much less appreciate, about my love for them. Some of that was my own reluctance to engage in deep emotional exchanges, which has left them with a balance of communication that strongly tilted towards the critical or correctional. They do not know, however, how I had lingered over them as they slept, hoping to freeze the moment… then quietly planted kisses on their foreheads lest their sleep should be disturbed. Nor do they know the times that I had prayed from the heart for them, such as for their relief from loneliness through a new and as yet unknown but wholesome best friend.

You have certainly expressed your love for me in concrete ways that I have learned to appreciate only by becoming a father myself. It is no easy task to provide for children’s upbringing and education, especially through the major crises that life often brings. I am definitely grateful to you for those things, for even material benefits to one’s children do not come apart from the Cross and its ordinary tortures of love. I especially remember how you insisted on regular provision of my foreign remittances throughout college despite the catastrophe of being a political prisoner during those dark years of oppression in the late seventies and early eighties. I also remember how you went out of your way to visit me during your covert trips to the States on behalf of the Light A Fire movement, though I was not quite appreciative then… The most signal memory I have though is much more ancient. I was a Prep student in Ateneo, waiting for you to pick me up from school in the late afternoon, when a group of older bullies stuffed me into a grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes, then stole my shoes as they taunted me. It still brings on powerful emotions to recall how you rushed out of the car and berated my tormentors, then carried me away in your arms as I cried in pain because of the injustice of my persecution. I regard that childhood memory as something of a metaphor for the crosses of my life, and God’s love and protection of me through Our Lady despite them.

Of the things I am most grateful to you for, the most important are the spiritual lessons that you imparted. Certainly your prayers and sufferings for my conversion as a young adult helped to ensure the fruitfulness of those lessons. In any case, it is to you that I most owe my love of Scripture, my love of the Eucharist, and my love of Our Lady. Those are three enormous gifts that I could never have received without your being my earthly father. I cherished the Bible that you and Mama gave me as an unanticipated and initially underappreciated gift for my 24th birthday when you were still a political prisoner. It was that Bible through which I received a supernatural gift… from the Holy Spirit, even as I opened it seriously for the first time. I also recall how you instructed me when I was yet in first grade how I ought to visit Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament whenever I had the chance. I retained that lesson throughout most of my adult life and continue to practice it. Lastly, it was your own love for the Mother of God that inspired me to turn to Her, particularly in my desire to grow in wisdom and knowledge, and more recently in love and mercy even as I learn only now what truly matters.

I hope I have managed to convey my gratitude and appreciation to you, even if imperfectly and at this very late stage. My prayer to God on your behalf is that He would bring forth the greatest fruit of love and mercy from your life, resulting not only in your salvation and sanctification, but in those of countless souls both within and beyond our family and country of birth.

May the grace and peace of Jesus Christ be with you, my father, as well as the assurance of my own love always and forever.

Your son,

Jay

I was indeed proven right about that visit being my last before Papa’s passing away. On the day that I found out about his death, I had a strange premonition. A word from Scripture came to me in my morning Lectio Divina, about the death of King David’s son Amnon at the hand of his other son, Absalom, which included the following verse: “So Absalom fled, and went to Geshur, and was there three years. And the spirit of the king longed to go forth to Absalom; for he was comforted about Amnon, seeing he was dead (2 Samuel 13:38-39).” I was bothered by the word I was given, thinking that it foretold a family disaster of some sort, a suspicion that appeared to be confirmed by the news of Papa’s death.

On contemplating the word from God, however, I was drawn to reflect on King David’s desire for his son, Absalom, despite Absalom’s guilt, and despite his physical distance from David. Then it hit me that perhaps I was Absalom, and that this was God’s calling attention to Papa’s love for me despite the circumstances that conspired to separate us for so many years. In the end, whatever those circumstances were have been rendered moot by God’s mercy and grace, poured out on my father, and through him on my entire family and yet many more. It is this mercy and grace to which his life and death are a testimony for the generations to come.

RELATED READING:

Why raps filed vs anti-Marcos freedom fighters in US

I will first describe Papa in the context of a journey that we all took as a family during 1970 to 1972, prior to the declaration of martial law in the Philippines. At that time, my father was a scholar at the Harvard Business School. He had been sent to Cambridge, Massachusetts by IBM, as a stepping stone to greater responsibilities within the company. Although Harvard is certainly a demanding institution, my father’s time apart from the corporate rat race gave us a chance to experience life in a different way. During this time, Papa saw to it that we, his children, had a rich set of experiences from which to draw for the rest of our lives.

Left photo: The author’s father, Eduardo B. Olaguer, then 44, was a geodetic engineer and professor at the Asian Institute of Management (AIM). Right photo: Jay Olaguer, then 20, was at the time an undergraduate Physics major in the United States. The photo was taken when Jay was interviewed by a Boston media reporter soon after his father was arrested in December 1979 along with several others for alleged subversion against the Philippine martial law government of then President Ferdinand E. Marcos.

I remember especially the long cross-continental summer trip that Papa instigated, some of which I would later retrace with my own children. I remember that he took my siblings and me to Fenway Park to watch the Red Sox play the Baltimore Orioles, the year the latter team was destined to win the World Series, and to the Boston Garden, to watch the Celtics play, when Dave Cowens and John Havlicek were still in their prime. I remember that Papa, my brother Eric, and I, would animatedly watch TV to see Bobby Orr and the big bad Bruins take on the rest of the National Hockey League on their way to a Stanley Cup in 1972, just before we left the States to return to the Philippines. I also remember the camping trips that Papa would take us on, including one to October Mountain State Forest, during which my sister, Didi, and I got lost following the wrong trail and ended up hitchhiking back to the family campsite. My father did not berate us then, as I had expected, but merely let us learn from our own mistakes.

With regard to the life of the mind, I remember the military history books Papa would buy, which he let me read while still a pre-teen, and which made deep and lasting contributions to my intellectual development. These were books like Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August, about the outbreak of the First World War, and a survey entitled, The Wars of America, which included a description of the so-called Philippine Insurrection, which deeply upset me along with another book on a similar subject entitled, Little Brown Brother. Indeed, I read many selections from Papa’s personal library, even strange and highfalutin books like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s The Divine Milieu, with which I would later disagree. This is one reason why, to this day, I hoard books like a precious treasure trove of knowledge and insight, in the hope that my own children and grandchildren will derive a similar love of learning.

When we returned to the Philippines in 1972, political events cast a shadow on our family life. I remember my father taking me, then thirteen years old, to a talk by former Justice Barrera of the Philippine Supreme Court, warning us of the loss of freedoms that martial law would bring. I would later learn that other controversial figures, some of whom we read about in the newspapers, would show up at our home in the middle of the night. My father would eventually resign from IBM due to his political stance. For some time, my parents continued to send us to exclusive schools, despite the fact discovered by my brother, Eric, that their bank deposit book showed a near-zero balance. But my father was a man of faith, a faith which God vindicated when Papa eventually took on a series of jobs that made him a leader in the business community.

As many of you in the audience know, the Light a Fire Movement that Papa helped to found landed my father in prison for over six years. In 1983, on a summer visit home from the States where I was by then a graduate student, I had the privilege of sneaking an overnight visit with Papa in his jail cell at Bicutan. That visit was the seed of my conversion back to the Catholic faith of my youth, facilitated by some heartfelt dialogue with my father on some very deep subjects, both personal and philosophical.

***

Fast forward to December 2014, when I was called home due to the discovery of an aneurysm in Papa’s chest, for which he required emergency surgery. Believing that it might be my last chance to see my father alive, I wrote him the following message prior to my visit:

Dearest Papa,

It’s been a long time since I’ve written a formal letter. Since I was informed of your upcoming heart surgery, it occurred to me that time was running out for saying certain things that needed to be said. We are both advancing in years, and neither of us is in the best of health. Moreover, events in the world are rapidly coming to a head. Who knows what the future holds?

The bottom line is that I have never properly expressed my gratitude to you for certain fundamental things in my life, and I did not want the opportunity to pass in order to finally come out and say it. After raising my own children, I am sure that there are some things that they will not likely ever know, much less appreciate, about my love for them. Some of that was my own reluctance to engage in deep emotional exchanges, which has left them with a balance of communication that strongly tilted towards the critical or correctional. They do not know, however, how I had lingered over them as they slept, hoping to freeze the moment… then quietly planted kisses on their foreheads lest their sleep should be disturbed. Nor do they know the times that I had prayed from the heart for them, such as for their relief from loneliness through a new and as yet unknown but wholesome best friend.

You have certainly expressed your love for me in concrete ways that I have learned to appreciate only by becoming a father myself. It is no easy task to provide for children’s upbringing and education, especially through the major crises that life often brings. I am definitely grateful to you for those things, for even material benefits to one’s children do not come apart from the Cross and its ordinary tortures of love. I especially remember how you insisted on regular provision of my foreign remittances throughout college despite the catastrophe of being a political prisoner during those dark years of oppression in the late seventies and early eighties. I also remember how you went out of your way to visit me during your covert trips to the States on behalf of the Light A Fire movement, though I was not quite appreciative then… The most signal memory I have though is much more ancient. I was a Prep student in Ateneo, waiting for you to pick me up from school in the late afternoon, when a group of older bullies stuffed me into a grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes, then stole my shoes as they taunted me. It still brings on powerful emotions to recall how you rushed out of the car and berated my tormentors, then carried me away in your arms as I cried in pain because of the injustice of my persecution. I regard that childhood memory as something of a metaphor for the crosses of my life, and God’s love and protection of me through Our Lady despite them.

Of the things I am most grateful to you for, the most important are the spiritual lessons that you imparted. Certainly your prayers and sufferings for my conversion as a young adult helped to ensure the fruitfulness of those lessons. In any case, it is to you that I most owe my love of Scripture, my love of the Eucharist, and my love of Our Lady. Those are three enormous gifts that I could never have received without your being my earthly father. I cherished the Bible that you and Mama gave me as an unanticipated and initially underappreciated gift for my 24th birthday when you were still a political prisoner. It was that Bible through which I received a supernatural gift… from the Holy Spirit, even as I opened it seriously for the first time. I also recall how you instructed me when I was yet in first grade how I ought to visit Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament whenever I had the chance. I retained that lesson throughout most of my adult life and continue to practice it. Lastly, it was your own love for the Mother of God that inspired me to turn to Her, particularly in my desire to grow in wisdom and knowledge, and more recently in love and mercy even as I learn only now what truly matters.

I hope I have managed to convey my gratitude and appreciation to you, even if imperfectly and at this very late stage. My prayer to God on your behalf is that He would bring forth the greatest fruit of love and mercy from your life, resulting not only in your salvation and sanctification, but in those of countless souls both within and beyond our family and country of birth.

May the grace and peace of Jesus Christ be with you, my father, as well as the assurance of my own love always and forever.

Your son,

Jay

***

I was indeed proven right about that visit being my last before Papa’s passing away. On the day that I found out about his death, I had a strange premonition. A word from Scripture came to me in my morning Lectio Divina, about the death of King David’s son Amnon at the hand of his other son, Absalom, which included the following verse: “So Absalom fled, and went to Geshur, and was there three years. And the spirit of the king longed to go forth to Absalom; for he was comforted about Amnon, seeing he was dead (2 Samuel 13:38-39).” I was bothered by the word I was given, thinking that it foretold a family disaster of some sort, a suspicion that appeared to be confirmed by the news of Papa’s death.

On contemplating the word from God, however, I was drawn to reflect on King David’s desire for his son, Absalom, despite Absalom’s guilt, and despite his physical distance from David. Then it hit me that perhaps I was Absalom, and that this was God’s calling attention to Papa’s love for me despite the circumstances that conspired to separate us for so many years. In the end, whatever those circumstances were have been rendered moot by God’s mercy and grace, poured out on my father, and through him on my entire family and yet many more. It is this mercy and grace to which his life and death are a testimony for the generations to come.

RELATED READING:

Why raps filed vs anti-Marcos freedom fighters in US