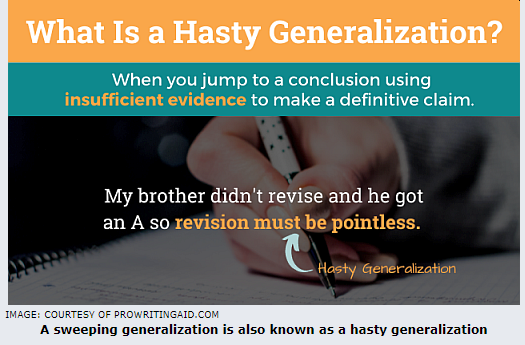

A common pitfall in writing is to mistake possibility or simple probability for certainty. Either from faulty grammar or faulty thinking, writers can make sweeping or hasty generalizations—statements that assert too much on too little evidence. They overstate their case and undermine the very argument they are making.

Consider this opening statement of a recent advice column: “Your greatest weakness is the one that you are unaware of. Because you do not know that it exists, you become vulnerable to the one who spots it.” By using the superlative “greatest” without qualification, this statement makes an assertion that can’t be possibly proven. Being unaware of a weakness doesn’t necessarily make it one’s greatest weakness; more likely, one’s greatest weakness would be the weakness one actually suffers from and is fully aware of. The premise thus proves logically indefensible.

A simple grammar fix can straighten the logic of such sweeping generalizations—by qualifying their premise as a possibility rather than an absolute certainty. See how the modal “could” efficiently eliminates the sweeping generalization from the statement above: “Your greatest weakness could be the one that you are unaware of. Because you do not know that it exists, you become vulnerable to the one who spots it.” Depending on the degree of possibility or conditionality, the modals “can,” “may,” and “might” can also be used to qualify such statements.

Logic is also violated when conditional statements are treated as absolute truths. Take this lead sentence of a newspaper feature story many years back: “Did you know that the country’s top chefs get their ingredients from Farmers Market in the Araneta Center in Cubao?” Although the story cites six Metro Manila-based chefs as getting their ingredients from the same market, this statement turns out to be a sweeping generalization because (1) it makes the unwarranted general claim that the country’s top chefs get their ingredients from that market, and (2) it makes the gratuitous implication that the five chefs mentioned in the story are the country’s top chefs, although they are only cited as examples of Metro Manila chefs sourcing their ingredients from the same market.

Such breaches of logic can be avoided by properly qualifying words or phrases that imply totality. See how much more credible the statement above becomes when we use “many” to qualify “the country’s top chiefs”: “Did you know that many of the country’s top chefs get their ingredients from Farmers Market in the Araneta Center in Cubao?”

When proving a point, we must also beware the all-too-common temptation to use “all” for “some” or “most,” “none” for “few” or “hardly anyone” or “hardly anybody,” “always” for “usually” or “frequently,” “surely” for “probably” or “perhaps,” and “never” for “rarely” or “seldom.” One single imprecise qualifier can throw our statements out of kilter.

For instance, even allowing for literary license, the following lead statement of a newspaper personality feature (the subject’s identity has been changed) obviously oversteps the bounds of its argument: “All her life [italics mine], Jennifer del Mar wanted to be a schoolteacher to help her poor parents make ends meet.”

By changing the qualifier “all her life” to “even as a child,” the statement gets a better temporal perspective by being made more realistic: “Even as a child, Jennifer del Mar already dreamed to be a schoolteacher so she could help her poor parents make ends meet.”

In face-to-face interactions, making sweeping generalizations may not be so harmful because our listeners will usually prompt us and give us the opportunity to qualify our statements until their intended meaning gets clear enough. When we make sweeping generalizations in writing, however, we risk being totally misunderstood or being deemed unreliable because the opportunity to qualify our ideas will no longer be available.

----------------

This is an abridged version of the author's 794-word 2003 essay that later formed part of his book Give Your English The Winning Edge

(480 pages, ©2009 published by the Manila Times Publishing Corp., Manila, Philippines). This essay, 2126th of the series, appears in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Campus Press section of the November 24, 2022 digital edition of The Manila Times

, ©2022 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.Read this essay in

The Manila Times:

The perils of sweeping generalizations (Next week:

Making effective paragraph transitions - 1) December 1, 2022

Visit Jose Carillo’s English Forum, http://josecarilloforum.com. You can follow me on Facebook and Twitter and e-mail me at j8carillo@yahoo.com