51

Getting to Know English / How the conjunctions “even though” and “even if” differ

« Last post by Joe Carillo on January 18, 2024, 05:10:33 AM »A Filipina writer based in the Middle East requested me in mid-2017 for a refresher on the difference between “even though” and “even if.” I don’t recall having discussed the subject in this column nor in Jose Carillo’s English Forum over the years, but I had noticed that some writers—even professional ones—tend to use those two contrastive conjunctions interchangeably. I was therefore glad that the writer, Forum member Miss Mae, asked me to clarify their proper usage.

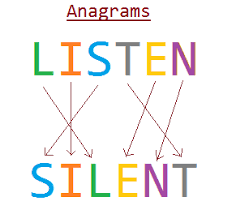

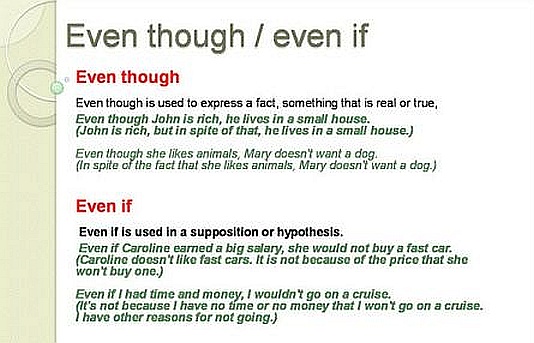

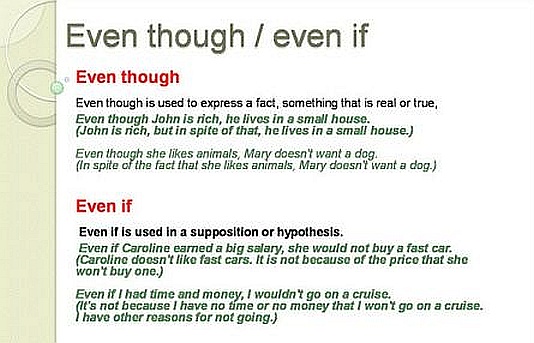

To begin with, I’d like to emphasize that as a rule, “even though” and “even if” are not interchangeable. “Even though” is used to express a fact or something that’s real or true, while “even if” is used in a supposition or for something imagined or unreal.

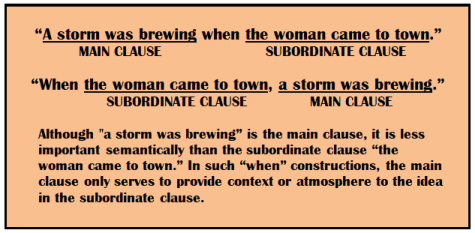

The sense of “even though” is “despite the fact that” or “in spite of the fact that,” which is an emphatic way of saying “though” and “although,” as in “Even though the woman searched the park for hours, she found no trace of her lost dog.” Here, the subordinate clause “even though the woman searched the park for hours” presents a contrastive factual premise to the outcome that she “found no trace of her lost dog.”

In contrast, the sense of “even if” is “regardless of what the condition might be” or “whether or not a particular condition or situation applies,” as in “Even if it floods in Manila tonight, I have to make it to the airport for my flight to Sydney.” Here, the subordinate clause “even if it floods in Manila tonight” is a conjectural condition in opposition to the speaker’s firmness in making it to the airport for his flight.

As a rule, “even if” is used for an unreal situation or supposition, as in “Even if I had the money, I wouldn’t buy that gaudy car” (the reality is the speaker doesn’t have the money); and “even though” for a real situation with an unexpected outcome, as in “Even though I have the money, there’s nothing I can buy it with in this expensive neighborhood” (the reality is the speaker does have the money).

There are possible borderline cases, though, where both “even though” and “even if” will work. This depends on the speaker’s belief or frame of mind. Take this question: “What makes you insist on running for president even though you are not qualified?” Here, the questioner is convinced or knows that the person referred is, in fact, unqualified. In contrast, if the questioner is unsure if that person isn’t qualified, “even if” could be used as well: “What makes you insist on running for president even if you are not qualified?”

This other grammar question was posted by Edward G. Lim a few days earlier on my Facebook page:

“Hi, Joe! I heard a couple of years ago a gentleman who said ‘I’m satisfied of what I’ve done in boxing.’ It doesn’t sound right to me. ‘Satisfied of’ isn’t a common construction, but why is it wrong, if it is indeed wrong? The more I hear such constructions, the more they sound acceptable to me.”

My reply to Edward:

The sentence you presented doesn’t sound right to me either. The right usage is “satisfied with”: “I’m satisfied with what I’ve done in boxing.” This doesn’t mean though that “satisfied of” is grammatically wrong; it just so happens that “satisfied with” is the widely accepted usage.

There’s really no inherent, arguable logic in using the preposition “with” rather than “of” after the adjective “satisfied”; educated native English speakers just happen to have grown accustomed to saying “satisfied with.” In fact, if you happen to be marooned in an island where the idiom is “satisfied of” among a population of, say, 100 English speakers, you’d surely find it acceptable and sounding right in perhaps less than a year.

Read this essay and listen to its voice recording in The Manila Times:

How the conjunctions “even though” and “even if” differ

(Next: Looking back to a bad English grammar syndrome) January 25, 2024

Visit Jose Carillo’s English Forum, http://josecarilloforum.com. You can follow me on Facebook and X (Twitter) and e-mail me at j8carillo@yahoo.com.

To begin with, I’d like to emphasize that as a rule, “even though” and “even if” are not interchangeable. “Even though” is used to express a fact or something that’s real or true, while “even if” is used in a supposition or for something imagined or unreal.

The sense of “even though” is “despite the fact that” or “in spite of the fact that,” which is an emphatic way of saying “though” and “although,” as in “Even though the woman searched the park for hours, she found no trace of her lost dog.” Here, the subordinate clause “even though the woman searched the park for hours” presents a contrastive factual premise to the outcome that she “found no trace of her lost dog.”

In contrast, the sense of “even if” is “regardless of what the condition might be” or “whether or not a particular condition or situation applies,” as in “Even if it floods in Manila tonight, I have to make it to the airport for my flight to Sydney.” Here, the subordinate clause “even if it floods in Manila tonight” is a conjectural condition in opposition to the speaker’s firmness in making it to the airport for his flight.

As a rule, “even if” is used for an unreal situation or supposition, as in “Even if I had the money, I wouldn’t buy that gaudy car” (the reality is the speaker doesn’t have the money); and “even though” for a real situation with an unexpected outcome, as in “Even though I have the money, there’s nothing I can buy it with in this expensive neighborhood” (the reality is the speaker does have the money).

There are possible borderline cases, though, where both “even though” and “even if” will work. This depends on the speaker’s belief or frame of mind. Take this question: “What makes you insist on running for president even though you are not qualified?” Here, the questioner is convinced or knows that the person referred is, in fact, unqualified. In contrast, if the questioner is unsure if that person isn’t qualified, “even if” could be used as well: “What makes you insist on running for president even if you are not qualified?”

***

This other grammar question was posted by Edward G. Lim a few days earlier on my Facebook page:

“Hi, Joe! I heard a couple of years ago a gentleman who said ‘I’m satisfied of what I’ve done in boxing.’ It doesn’t sound right to me. ‘Satisfied of’ isn’t a common construction, but why is it wrong, if it is indeed wrong? The more I hear such constructions, the more they sound acceptable to me.”

My reply to Edward:

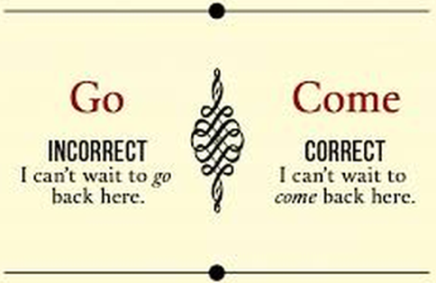

The sentence you presented doesn’t sound right to me either. The right usage is “satisfied with”: “I’m satisfied with what I’ve done in boxing.” This doesn’t mean though that “satisfied of” is grammatically wrong; it just so happens that “satisfied with” is the widely accepted usage.

There’s really no inherent, arguable logic in using the preposition “with” rather than “of” after the adjective “satisfied”; educated native English speakers just happen to have grown accustomed to saying “satisfied with.” In fact, if you happen to be marooned in an island where the idiom is “satisfied of” among a population of, say, 100 English speakers, you’d surely find it acceptable and sounding right in perhaps less than a year.

Read this essay and listen to its voice recording in The Manila Times:

How the conjunctions “even though” and “even if” differ

(Next: Looking back to a bad English grammar syndrome) January 25, 2024

Visit Jose Carillo’s English Forum, http://josecarilloforum.com. You can follow me on Facebook and X (Twitter) and e-mail me at j8carillo@yahoo.com.

Recent Posts

Recent Posts