We’ve already discussed five of the most common kinds of material fallacies—false cause, hasty generalizations, misapplied generalizations, false dilemma, and compound generalization—so we’ll now proceed to the remaining four:

false analogy,

contradictory premises,

circular reasoning, and

insufficient or suppressed evidence.

False analogy. When an analogy is drawn between dissimilar or totally unrelated objects or ideas, the result is the false, unreliable analogy that’s better known as the mangoes-and-bananas comparison: “Bananas are as delicious and tasty as mangoes.” But here’s a more complex, deceiving example: “Minds, like rivers, can be broad. The broader the river, the shallower it is. Therefore, the broader the mind, the shallower it is.” On closer scrutiny, we find this analogy to be false because minds (abstract) and rivers (physical) are actually totally dissimilar and unrelated objects.

We all know how powerful an analogy could be. It can persuade us to transfer the feeling of certainty we have about one subject to another subject that we may not have an opinion yet. But we must be extremely cautious with such analogies because they rely on the questionable principle that because two things are similar in some respects, they’d be similar in some other respects. Indeed, when relevant differences outweigh relevant similarities, a false analogy results.

Contradictory premises. A basic rule in logic is that a conclusion is valid only when its premises don’t contradict one another; thus, an argument with conflicting or inconsistent premises is automatically invalid, as in this classical question: “What will happen if an irresistible force meets an immovable object?” The fallacy here is that in a universe where an irresistible force exists, no immovable object could also exist because it would negate the existence of that irresistible force.

Two more of these brain-bending fallacies: “Into what shape of a slot would a rectangular circle fit?” “If God is all-powerful, can he create a rock so huge and so heavy that He cannot lift it?” The premises of both of these questions can’t be valid, so there’s really no way of logically answering them.

Circular reasoning. This material fallacy results when the assertion to be proved is later used in the argument as an already-proven fact. Also known as “begging the question” (

petitio principii in Latin), circular reasoning is common even among the intelligent; people just have a natural predisposition to it.

We sometimes engage in varying degrees of self-deception to keep our self-respect or massage our egos: “I must be good-looking because I really think so.” “Although I take bribes as a government official, I’m a man of integrity because I treat people well and give generously to charity.” (Clearly, though, charity and kindness of this type don’t prove integrity.)

Circular reasoning becomes dangerous when large sectors of the population actively pursue as a way of life and as communal pastime: “He will be a good president because he’s already extremely wealthy and will have no more motivation to pocket public funds.”

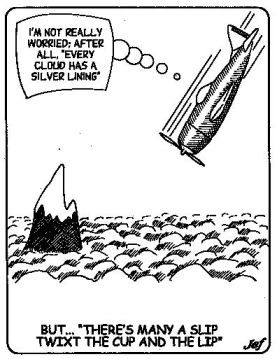

Insufficient or suppressed evidence. This is the material fallacy that (1) uses as proof only the facts that support the predetermined conclusion, or (2) disregards or ignores all other pertinent facts. A loyal handmaiden of circular reasoning, this form of illogic gently prods people to close their minds to contrary evidence and decide solely on gut-feel.

Take these two examples: “This buffoon makes me laugh so I’ll vote for him as president; he has no public service experience, but he’s a fast learner so I’m sure he’ll learn to govern fast enough.” “We’ve had bright lawyer-presidents who just misgoverned our country terribly, so this time I’m voting for any trustworthy nonlawyer even with low IQ.”

We’ll move on next week to the second broad category of logical fallacies—the fallacies of relevance.

(Next:

Watching out against the fallacies of relevance – 1) August 10, 2017

This essay, 1051st of a series, appeared in the weekly column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Education Section of

This essay, 1051st of a series, appeared in the weekly column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Education Section of The Manila Times

, August 3, 2017 issue (print edition only), © 2017 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.RETROSPECTIVE - THE FULL SERIES ON LOGICAL FALLACIES:July 20, 2017:

Watching out against the material fallacies – 1July 27, 2017:

Watching out against the material fallacies – 2August 10, 2017:

Watching out against the fallacies of relevance – 1August 17, 2017:

Watching out against the fallacies of relevance – 2August 24, 2017:

Watching out against the fallacies of relevance – 3August 31, 2017:

Watching out against the fallacies of relevance – 4September 7, 2017:

Watching out against the verbal fallacies – 1September 14, 2017:

Watching out against the verbal fallacies – 2