English in a Used JarBy Jose A. CarilloThe other summer I tried to interest my two sons, then 15 and 9, in learning a third or fourth language. For their age they were already admirably fluent in English and Tagalog, so I thought that perhaps they should learn French, Japanese, or Chinese to give them the edge not only in school but in their future careers as well. I also had an ulterior motive in wanting them to do so. They were using too much time and energy playing those extremely violent Japanese-language computer games. I figured that they might as well put their amazing computer proficiency to use in something more educational, intellectual, and useful in the long term.

The language program that I wanted my sons to get into was an impressive multimedia routine entitled “The Rosetta Stone.” It offered a suite of 24 languages, if I remember my figures correctly, ranging from Dutch to Swahili and from German to Polynesian. I had found the program on the Worldwide Web and I took great interest in it because of a sad experience I had in my early teens. Tantalized by Ian Fleming’s accounts of the romantic adventures of James Bond behind the Iron Curtain, I had tried to learn Russian single-handedly. With no tutor and learning tapes and with only a battered English-Russian dictionary from a Peace Corps volunteer who had hurriedly flown back to the United States, that enterprise withered in the bud in less than two weeks.

My sons at first took to Rosetta Stone like butterflies to nectar. The older one began honing his piddling Japanese and also took a fancy to German after a day or two. The younger focused his learning resources on French exclusively, and in three days’ time was already speaking a smattering of the language complete with the schwas and the nasals. But less than a week after that, their elder sister came home from overseas and gifted them with a three-dimensional CD on time travel entitled “The Messenger.” That, in short, was the end (only for the time being, I hope) of Rosetta Stone and of my dream that my sons would become multilingual before entering college.

My predicament with my sons brought back memories of my own travails in learning English in grade school, back in my farming hometown in those years when there were yet no TV sets, no audio-visuals, no computers, and certainly no multimedia educational tools like Rosetta Stone. The only good thing going for us were our teachers, a hardy breed that rarely displayed lawyerly eloquence in English but was deeply steeped in the learning and teaching discipline. What they lacked in method and tools, they amply compensated for in native resourcefulness. And what they did to make their pupils learn English was simplicity itself.

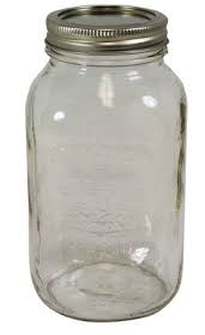

Our teachers made the whole school compound a strictly English-speaking zone. We were absolutely forbidden to speak any other language or dialect anywhere inside. This rule was rigorously enforced through a used two-ounce glass jar of mayonnaise or pickles. It was labeled “I was caught not speaking English,” and every time you used the vernacular or Chinese or Hindi, you were obliged under a strict honor system to accept the glass jar and drop a five-centavo coin into it as penalty. You had to screw back the cap and furtively prowl the campus to catch another dialect-speaking violator in the very act and, bingo! the glass jar—plus his five-centavo penalty—could now be transferred to his custody. At day’s end, the last pupil with the glass jar had to surrender it to the teacher and formally remit the coins.

Oh, there were all sorts of complaints from parents and pupils alike against the dictatorship of the glass jar. There were several brawls and blackeyes among early jar passers and receivers. But after a week or two, the pupils got the hang of it and started doing their damnedest best to speak straight and fluent English. The complaints stopped, and in a few months pupils from the school began winning English declamation contests at higher and higher interscholastic levels. In my case, I was an inveterate dialect-cursing maverick when the glass jar campaign started, but I learned my lessons early enough. I learned to hate being handed the jar and parting away with my five-centavo coins, which was a big drain on my school allowance. So one day, I just decided to converse and curse consistently in English to bring down my contributions to the glass jar literally to zero.

Looking back to those days now, there is absolutely no doubt in my mind that if not for that used glass jar, I would not be writing this little piece in English at all. At this very moment I would likely be already out in the old farm, tilling the family’s small parcel of riceland with a carabao-drawn plow, and certain to be doing the same for the rest of my life. Not that I would have hated farming, whose utterly predictable procession of planting, growing, and harvesting has a poignant way of giving you inner peace. But truth to tell, nothing really compares with the psychic reward of getting your thoughts printed in English and having a receptive audience for them. (circa 2002)

This essay first appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in The Manila Times

in 2002 and subsequently appeared in Jose Carillo’s book English Plain and Simple: No-Nonsense Ways to Learn Today’s Global Language

. Copyright © 2004 by Jose A. Carillo. Copyright © 2008 by Manila Times Publishing. All rights reserved.---------

This forms part of the collection of his personal essays that the author has been posting in the Forum every Wednesday from October 26, 2016 onwards.