21

Site Announcements / Playlist Update (February 22-28, 2025) of Jose Carillo Forum's Facebook Gateway

« Last post by Joe Carillo on February 26, 2025, 06:54:40 PM »PLAYLIST UPDATE FOR FEBRUARY 22 - 28, 2025 OF JOSE CARILLO ENGLISH FORUM’S FACEBOOK GATEWAY

Simply click the web links to the 15 featured English grammar refreshers and general interest stories this week along with selected postings published in the Forum in previous years:

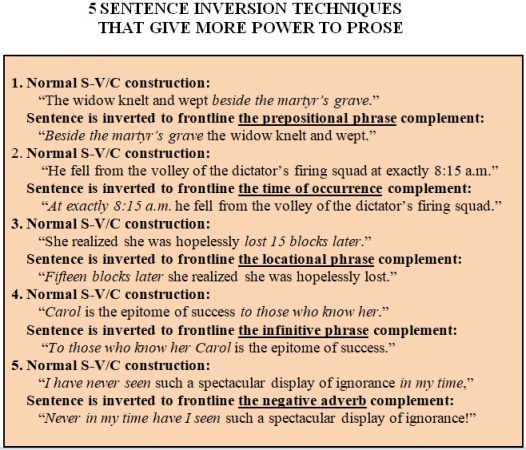

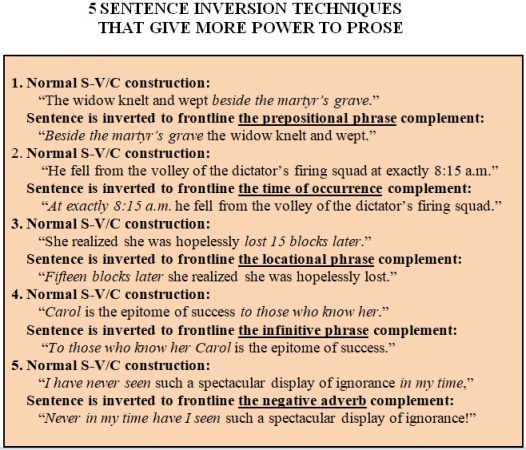

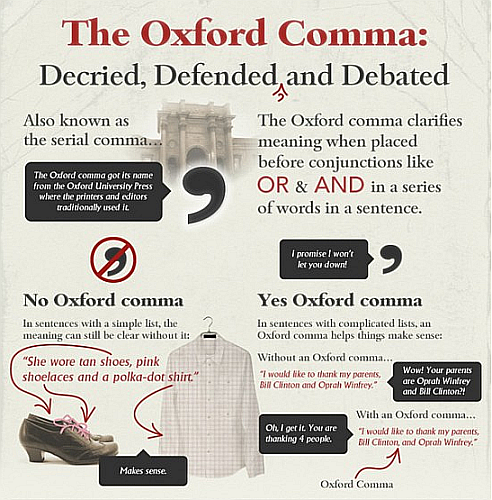

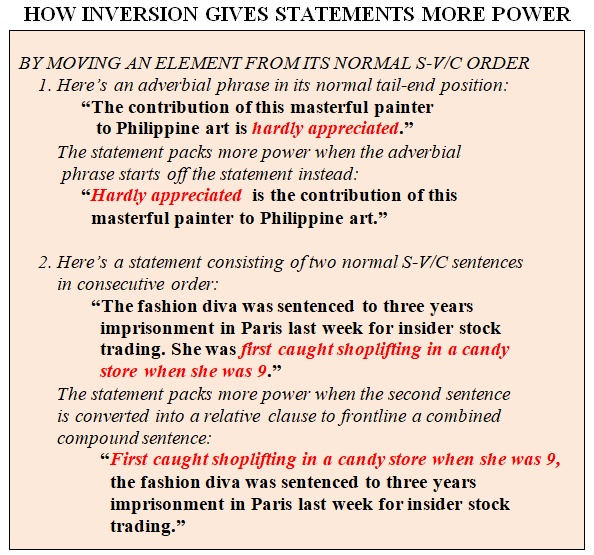

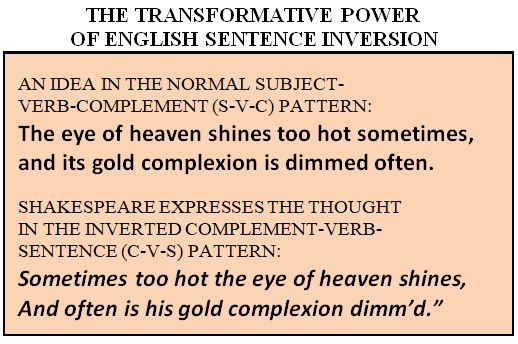

1. Getting To Know English: “Using inversion for even stronger emphasis”

2. Use and Misuse: “Can we use the American word ‘thru’ and British word ‘through’ interchangeably?”

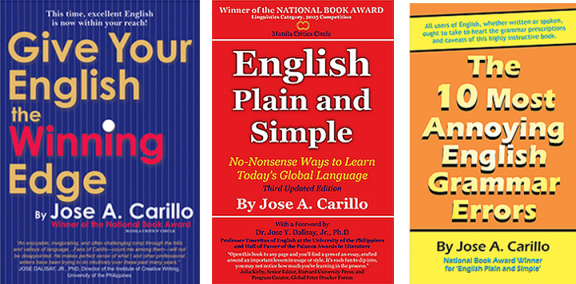

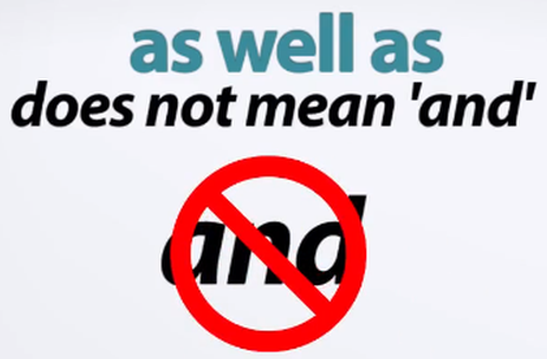

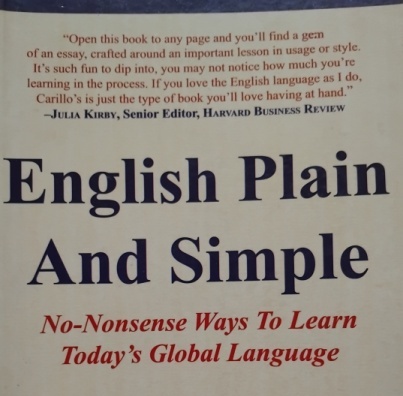

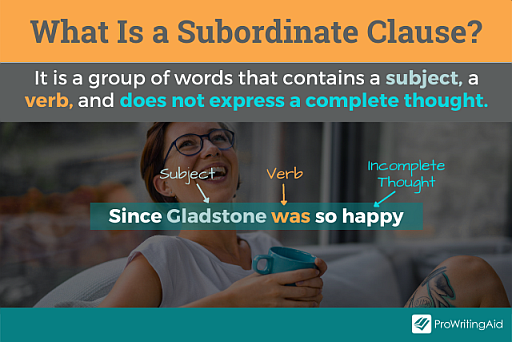

IMAGE CREDIT: PROWRITINGAID.COM

3. Badly Written, Badly Spoken: “Why must ‘brothers and sisters’ be shortened to ‘brethren’?” (The Forum's reply to a very challenging grammar question raised by Forum Member Miss Mae way back in November 2011)

4. You Asked Me This Question: “How ‘on the contrary’ and ‘to the contrary’ differ”

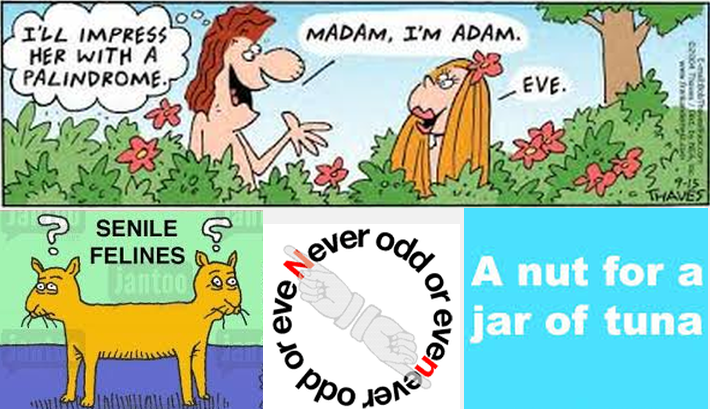

5. My Media English Watch: “The adjective ‘naked’ gets misplaced in an online news headline”

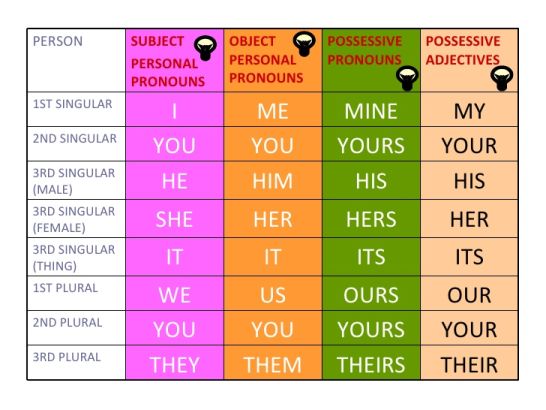

6. Getting to Know English: “How the three kinds of objects work in English grammar”

7. Essays by Jose A. Carillo: “The wonderful thing called ‘voice’”

8. Students’ Sounding Board: “When is sentence inversion a matter of grammar or style?”

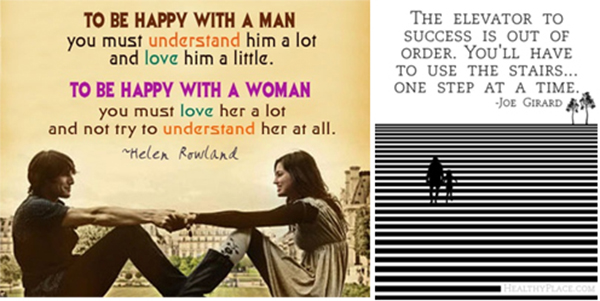

9. Language Humor at its Finest: “A treasury of funny quotes and outrageous sayings”

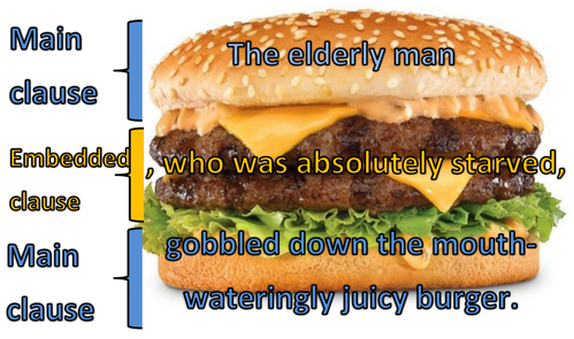

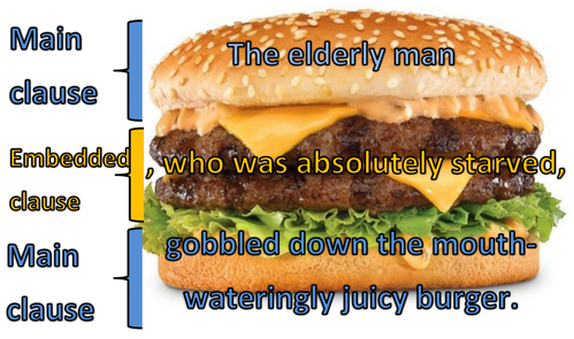

10. Going Deeper Into Language Retrospective: "The relative importance of main clauses and subordinate clauses”

11. A Forum Lounge Retrospective: "A Beauty and a Love Verboten," personal reminiscence in 2012 by Forum Contributor Angel B. Casillan

12. Time Out from English Grammar: "Are you truly conscious, or just an advanced illusion of thought?" British evolutionary biologist-zoologist Richard Dawkins posts in his personal website a chat between him and ChatGPT

13. Advice and Dissent: “The Myth of Social Media and Populism: Why the moral panic is misplaced,” foreign policy commentary by Princeton University professor Jan-Werner Müller

14. Time Out From English Grammar: “A novelist in ill health races with time to finish a masterpiece”

15. A Forum Lounge Retrospective: “Two magnificent performances of ‘The Prayer,’ spaced 10 years apart

THE CHARLOTTE CHURCH-JOSH GROBAN

“THE PRAYER” 2002 LIVE CONCERT PERFORMANCE

THE CHARICE PEMPENGCO AND THE CANADIAN TENORS

“THE PRAYER” 2010 LIVE TV PERFORMANCE

Simply click the web links to the 15 featured English grammar refreshers and general interest stories this week along with selected postings published in the Forum in previous years:

1. Getting To Know English: “Using inversion for even stronger emphasis”

2. Use and Misuse: “Can we use the American word ‘thru’ and British word ‘through’ interchangeably?”

IMAGE CREDIT: PROWRITINGAID.COM

3. Badly Written, Badly Spoken: “Why must ‘brothers and sisters’ be shortened to ‘brethren’?” (The Forum's reply to a very challenging grammar question raised by Forum Member Miss Mae way back in November 2011)

4. You Asked Me This Question: “How ‘on the contrary’ and ‘to the contrary’ differ”

5. My Media English Watch: “The adjective ‘naked’ gets misplaced in an online news headline”

6. Getting to Know English: “How the three kinds of objects work in English grammar”

7. Essays by Jose A. Carillo: “The wonderful thing called ‘voice’”

8. Students’ Sounding Board: “When is sentence inversion a matter of grammar or style?”

9. Language Humor at its Finest: “A treasury of funny quotes and outrageous sayings”

10. Going Deeper Into Language Retrospective: "The relative importance of main clauses and subordinate clauses”

11. A Forum Lounge Retrospective: "A Beauty and a Love Verboten," personal reminiscence in 2012 by Forum Contributor Angel B. Casillan

12. Time Out from English Grammar: "Are you truly conscious, or just an advanced illusion of thought?" British evolutionary biologist-zoologist Richard Dawkins posts in his personal website a chat between him and ChatGPT

13. Advice and Dissent: “The Myth of Social Media and Populism: Why the moral panic is misplaced,” foreign policy commentary by Princeton University professor Jan-Werner Müller

14. Time Out From English Grammar: “A novelist in ill health races with time to finish a masterpiece”

15. A Forum Lounge Retrospective: “Two magnificent performances of ‘The Prayer,’ spaced 10 years apart

THE CHARLOTTE CHURCH-JOSH GROBAN

“THE PRAYER” 2002 LIVE CONCERT PERFORMANCE

THE CHARICE PEMPENGCO AND THE CANADIAN TENORS

“THE PRAYER” 2010 LIVE TV PERFORMANCE

Recent Posts

Recent Posts

.png)