We will now discuss the last four of the six kinds of verbal fallacies, namely the fallacies of

amphiboly,

composition,

division, and

abstraction. Together with the fallacies of

ambiguity and of

equivocation that we took up last week, they comprise the third broad category of logical fallacies—false statements or conclusions that result when words are used improperly or ambiguously.

Amphiboly. This fallacy results from ambiguous or faulty grammatical structures. The error isn’t with a specific word but with how the words connect or fail to connect. English is particularly susceptible to amphiboly because its vocabulary is so rich and its sentence structures so flexible. Some examples:

A grimly humorous example:

“Big Bargain: New highchair for toddler with a missing leg” (Without ambiguity: “Big Bargain: New toddler’s highchair with a missing leg”). Here, we have a misplaced modifying phrase that needed to be relocated to its proper place.

A classic case of amphiboly arises when the adverb “only” is variously positioned in these sentences: “

She only wrote that.” “

Only she wrote that.” “She wrote

only that.” “She wrote that

only.” When “only” is positioned such that the statement yields a meaning other than what’s intended, that statement is an amphiboly.

And newspaper headlines are often inadvertent purveyors of amphiboly:

“Juvenile Court to Try Shooting Defendant”;

“Red Tape Holds Up New Bridge”;

“Two Convicts Evade Noose: Jury Hung.”Composition. This is the fallacy of guilelessly assuming that a group of things or actions as a whole will have the same attributes as the individual things or actions that comprise it. Take these examples:

“A story made up of good paragraphs is a good story.” (Not necessarily, of course!)

“If someone stands up out of his seat at a basketball game, he can see better. Therefore, if everyone stands up they can all see better.”

“An elephant eats more food than a human; therefore, elephants as a group eat more food than do all the humans in the world.” (Do your math; we humans grossly outnumber the elephants, so we consume more food than they overall.)

Division.

Division. The converse of the fallacy of composition, the fallacy of division wrongly assumes that the individuals in a group have the same qualities as the group itself. In reality, though, what is true of the whole isn’t necessarily true of its parts. Consider these fallacies of division:

“The universe has existed for 15 billion years. The universe is made out of molecules. Therefore, each of the molecules in the universe has existed for 15 billion years.

“Female professionals in the Philippines are paid less than their male counterparts. Therefore, my Mom earns less money than my Dad.” (Not necessarily!)

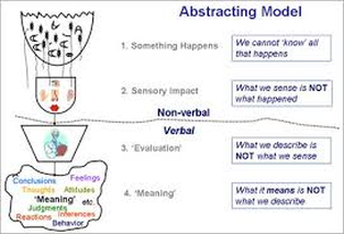

Abstraction.

Abstraction. This fallacy is the classical error of postulating or believing that everything that one comprehends through pure reasoning can actually happen in reality. Take the audacious illogic of this quote in a familiar inspirational poster:

“Everything your mind can conceive, your body can achieve.” Sounds like a very desirable possibility, but saying it is actually the height of naiveté or ignorance about the ways of the world.

Another form of the abstraction fallacy is taking a quoted statement out of context. For example, a London newspaper carried this negative critique of a theatrical performance:

“I couldn’t help feeling that, for all the energy, razzmatazz and technical wizardry, the audience had been shortchanged.” However, the stage play promoters deviously pared down that statement to this blurb in their newspaper ads for that play:

“…having ‘energy, razzmatazz and technical wizardry.’” That’s a fallacy of abstraction that shamelessly distorts the intent and spirit of the original statement.

Vigilance over language—whether our own or those of others—is actually our only sure and effective line of defense against the verbal fallacies.

(Next week:

Epilogue: Teaching our children to think logically) September 21, 2017

This essay appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Education Section of the September 14, 2017 issue (print edition only) of

This essay appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Education Section of the September 14, 2017 issue (print edition only) of The Manila Times

, © 2017 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.